Section 3.2 What is sense?

The characterization of word meaning as involving a “concept” or “knowledge structure” could suggest that the meaning (sense) of a word is the set of all things that members of a language community know about the category of entities to which the word refers.

But this is not plausible. Look at the following list of things that a language user could know about trees:

-

is a plant

-

can become taller than any other plant

-

is made of wood

-

has a single stem

-

has leaves

-

has branches in the upper part of the stem

-

has roots

-

is able to live for many years

-

evolved 400 million years ago

-

produces its stem by secondary growth

-

removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

-

can belong to many different species

-

is an angiosperm or a gymnosperm

-

reduces the erosion of soil

-

provides a habitat for birds

-

provides shade on sunny days

-

some kinds are used as timber

-

some kinds have fruit that we can eat

-

some kinds are sometimes put into people’s houses and decorated for Christmas

-

one of them stands in front of my house

-

a friend of mine fell from one and broke both their arms

This list illustrates a range of problems with the idea that the meaning of the word tree consists of our knowledge of trees. First it is not complete, nor can it be: there are innumerable things members of a language community may know about a given category.

Second, the list contains properties that most language users are unaware of. Unless you are a biologist specializing in dendrology (the study of woody plants), you probably did not know that trees produce their stem by secondary growth or that they can be angiosperms of gymnosperms. Worse, it is likely that you have no idea what either of these statements means, even though you now know them to be true.

Third, even among the properties on the list that are widely known outside of dendrology, there are some that most language users rarely think about when they use the word tree — for example, that trees are able to live for many years or that they provide a habitat for birds.

Fourth, not every member of a language community will know, or regularly think about, the same properties of an entity. Some of your family and friends will know that trees remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, some won’t, some will often think about birds nesting in trees, some won’t. In fact, some of the things we might know about trees are entirely subjective — not all readers of this book will have a tree in front of their house, and only a tiny portion will have a friend who fell from a tree and broke both their arms.

Fifth, some of the properties are present in individual entities in the extension of the word tree at all times — all trees are plants and all trees are woody. But other properties are not present in all trees — some individual trees have branches that begin very close to the ground, or they have no branches at all (for example, due to a lightning strike). And other properties are not present all the time — for example, many trees lose their leaves in the winter.

A slightly different problem is that, sixth, are also entire sets of entities in the extension of the word tree that do not share one or more of the properties listed. Not all types of trees can be used for timber, have fruit that we can eat or are used as Christmas decoration. Even some of the central properties are not shared by all types of trees — for example, some do not grow taller than other plants, such as the Honshū maple (acer rufinerve), which has a maximum height of 7 metres, while there are cacti and fern that can grow to a height of more than 20 meters.

Subsection Meaning and knowledge

Let us look at these issues begin with the first four. These all show that there must be a difference between the knowledge structures corresponding to the meaning of a word and the knowledge structures capturing what language users have about its referents. In linguistics, this difference is often presented as that between a dictionary (which contains word senses as part of what we call linguistic knowledge) and an encyclopedia (which contains what we call encyclopedic knowledge (or world knowledge), i.e., the sum of what members of a language community can know about categories of entities.

There are different suggestions as to where to draw the line between these two types of knowledge. One suggestion is that word senses (linguistic knowledge) is restricted to those properties that are individually necessary and collectively sufficient to distinguish categories of entities from each other. For the word tree, these properties could be the following:

Each of these properties is a necessary condition for inclusion in the category TREE — if an entity does not have all three properties, it is not a tree. None of the properties are unique to trees — there are other plants (such as bushes, flowers, herbs, grasses, etc.), there are other entities that consist of wood (such as bushes, certain kinds of furniture, the framing of certain types of houses, etc), and there are other entities that have a single stem (such as flowers, wine glasses, etc.). However, taken together, they are sufficient for inclusion in the category TREE: the first property distinguishes trees from people, animals, rocks, manufactured objects, etc., the second property distinguishes trees from all other plants except shrubs, and the third property distinguishes trees from shrubs. Therefore, any entity that has all three properties is a tree, or, to put it differently, the statement “x is a tree” is true if (and only if) x has these three properties.

At first glance, the idea that word meanings can be captured in terms of such necessary and sufficient conditions is very attractive, but a closer look shows that it is not without problems. Crucially, a set of necessary and sufficient conditions typically excludes properties that seem just as central to the intension of a word as those that are included. For example, are the fact that a trees have branches and leaves less relevant that the fact that they have a single stem? Sure, we do not need to include them in order to distinguish trees from other entities, but it is implausible that they are less important to the concept associated with the word tree than the three necessary and sufficient properties listed above. In other words, it is not clear that this approach can really help us draw the line between linguistic knowledge and world knowledge.

Even more problematically, it is often possible to come up with a set of necessary and sufficient conditions that does not correspond to our intuition as to a word’s meaning at all. The Greek philosopher Plato is reported to have defined the word human being (ἄνθρωπος) as a ‘two-footed unfeathered animal’ (ζῷον δίπουν ἄπτερον). It is certainly true that the features ‘has two feet’ distinguish humans from all other entities except birds, and ‘unfeathered’ distinguishes them from birds, so collectively, these two properties are necessary and sufficient to distinguish humans from all other entities. But the idea that ‘unfeathered two-footed animal’ is actually the meaning of the word human being is very hard to swallow.

The problem can be mitigated by choosing necessary and sufficient properties more carefully. For example, the linguist Robbins Burling calls humans the talking ape in the title of a famous book. He did not intend this to be a definition, but if you think about it, ‘can talk’ and ‘is a primate’ are also individually necessary and collectively sufficient properties distinguishing humans from other entities.

They also they feel much more central to the meaning of human than the features ‘does not have feathers’ and ‘has two legs’. But this is actually an argument against the idea that the meaning of words can be captured in terms of necessary and sufficient properties: if this idea were right, any such definition should be equally good. The fact that “talking ape” feels closer to the meaning of human than “unfeathered two-footed animal” shows that the intension of the word human is not limited to either of these — or indeed any other smallest possible set of properties.

Another approach to distinguishing word meaning from world knowledge focuses on the shared nature of language: we use words to communicate, and for this to be possible, their meaning must be shared. It would make sense, therefore, if language users made certain assumptions about what parts of their knowledge are shared by the whole speech community and what parts are not — the intension of a word would then include the properties that are generally assumed to be shared.

This would eliminate most of the problematic properties listed for the concept TREE at the beginning of the chapter: those only known to experts or rarely thought about, as well as those limited to the experience of a few individuals. We would be left with something like the following features, which are the ones typically mentioned in dictionaries:

-

is a plant

-

can become very tall

-

is woody

-

has a single stem

-

has branches in the upper part of the stem

-

has green, flat leaves

Subsection Meaning, canonicity and idealised models

Let us now turn to the fifth problem mentioned above: even though we can use the ideas in the preceding subsection to distinguish between the intension of a word and our knowledge about the entities it refers to, this intension will often contain properties that are not shared by every individual entity in the category.

It is said that when Plato suggested the definition ‘unfeathered two-footed animal’ for the word human being, the philosopher Diogenes (the one who supposedly lived in a large ceramic jar) plucked a chicken and presented it with the words “Here is Plato’s human being”. While he presumably got a laugh out of this stunt, it is not actually an argument against Plato’s definition — Plato was assuming what we can call the default (or canonical) state of humans and birds — humans do not have feathers by default, birds do. Of course you can pluck a bird or stick feathers on a human, but every member of the language community knows that this is not the expected state of these entities.

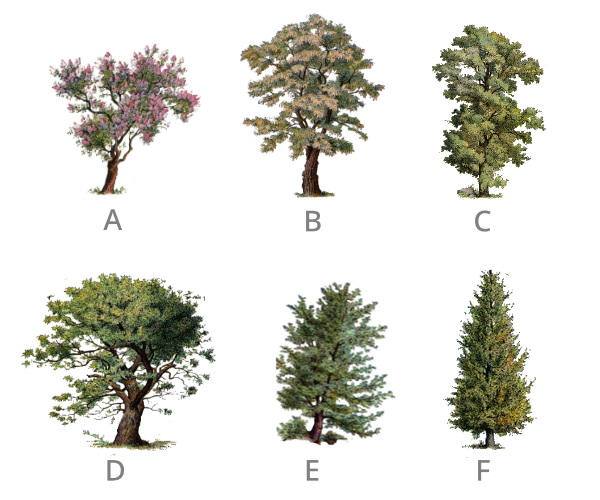

Look at the second tree in Figure 3.2.1 — it violates the property “has a single stem”, which we included in the intension of the word tree just now: its stem splits into two separate stems before well below the point at which the branches begin.

Five trees in a row: A) a tree with pink blossoms, B) a decidous tree with branches along the entire trunk, C) a decidous tree with branches growing only in the upper part, D) a coniferous tree with a roundish shape, E) a coniferous tree with a triangular shape

This can happen for various reasons — for example, due to damage to the stem at an early stage in the tree’s life, because two trees grow very close together and fuse, because a branch happens to grow upwards becoming its own stem. As in the case of Diogenes’ plucked chicken, language users know that this is not the default situation but an exceptional one, so it does not affect the intension of the word tree.

More generally, we can say that the intension of a word always reflects assumptions about a default or canonical state of affairs. Language users know that individual members of a category may deviate from this default state for various reasons, but that is encyclopedic knowledge.

Things are a little more complex when there are sets of entities that do not share a particular property in the intension of a word. To illustrate this, look at Figure 3.2.1 once again and answer the following question: When you hear the word tree, without any additional context, which of the trees shown matches your mental image most closely?

It is probably the one labeled D. But why is this the case, and why can we answer this question in the first place? After all, all of the entities shown are clearly and unambiguously trees!

The reason seems to be that it is one of only two trees shown that has all of the properties included in the intension of the word tree given above: the trees in B, E and F deviate from this intension in that they have branches beginning in the lower part of their stem, and while the green growths that the trees in E and F have are leaves from a biologist’s perspective, we would not call them leaf in everyday language — to us, they are needles. This leaves trees A and D, but A has pink petals instead of green leaves.

These deviations are not associated with individual trees, but with whole species of trees, so we can not discard them by appealing to a default, as we did in the case of split stems or missing branches. We could, of course, remove all of these properties from the intension of the word tree, which would bring us back to the definition in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions. But if we did that, how would we explain that the tree labeled D is, somehow, a more typical tree than the other five?

A reasonable suggestion is that our linguistic model of the world is simpler than the world itself — in our idealized model, there is only one kind of tree — one that has all the properties listed above. When we apply this model to the actual world, it fits well enough, but it does not always fit perfectly — because we know that the world is complex, we tolerate a number of mismatches. On the one hand, this can lead to fuzzy boundaries — we cannot draw an exact boundary between trees and bushes, for example. On the other hand, it can lead to so-called prototype effects, where entities that do match our idealized model perfectly are felt to be “better” examples of a category than others.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Written by Anatol Stefanowitsch