Give the same type of definition for the words woman, man, and girl.

Section 3.3 Representing meaning

You may have noticed a certain fuzzyness in the way we have defined and represented linguistic meanings. We have used terms like “concept”, “mental representation” and “knowledge structure” to define it and we have used three types of notation to represent it: a word in upper case letters, as in (1), that is meant to be a short hand for a more comprehensive description, which can take the form of a dictionary-like definition, as in (2), or a list of what we called “properties” or “features”, as in (3):

- (1)

- TREE

- (2)

- ‘a long-lived plant with a single thick wooden stem that grows to a great height, with branches growing from its upper part, and leaves’

- (3)

This fuzziness comes from the fact that meaning is a mental state, and mental states are difficult to define. The best definition we can think of is the following: the meaning of a linguistic sign is a mental state that is similar to the mental state caused by our direct experience of the referent of that sign or the relation between referents predicated by the sign. The meaning is more abstract than the mental state caused by a specific experience, however — it is the commonality between all specific experiences of the sign’s extension.

It is these mental states that we must try to represent when discussing linguistic meaning. The problem is that, as humans, we have evolved exactly one tool to represent any aspect of our experience: language. So, whatever the meaning of a word actually “is”, the only way we can represent it is using other words. This brings with it a number of problems that we cannot avoid, but that we must keep in mind.

Subsection Circularity and abstractness

The most straightforward way of representing the meaning of a word using other words is the type of dictionary-like definition shown in (2). repeated here in the format of an actual dictionary definition:

tree, n /tɹi/ a long-lived plant with a single thick wooden stem that grows to a great height, with branches growing from its upper part, and leaves

As we discussed, such a definition is an attempt to summarize part of the knowledge that language users have about the referent of the word — the part that is shared across language users and that feels central. We can now see why it is so difficult to decide where to draw the line between that knowledge and the encyclopedic knowledge we have about a referent: meanings are not really knowledge structures at all, but mental states echoing our direct experience of a referent — the knowledge presented in a dictionary definition is a description of the referent, not of the experience itself.

Since we cannot describe the experience itself, describing the referent may well be the best we can do. But even so, note that there is a problem: such descriptions use words that also have referents, so they rely on our experience of these referents. The definition of tree just given relies on the words plant, stem, branch, and leaf, among others. Of course, in order for the definition to capture our knowledge about potential referents of the word tree, these words would also have to be defined. Let us do so:

plant, n /plænt/ a living thing that grows in the earth, on surfaces or other plants, or in water, usually has roots, a stem and leaves, and produces seedsstem, n /stɛm/ a central, tube-shaped part of a plant that grows above the ground and to which branches or leaves are attachedbranch, n /bɹænt͡ʃ/ a part of a tree that grows from its stem and has leaves attached to itleaf, n /lif/ a flat part of a plant that is attached to a stem or branch

You can see the problem of circularity: the definition of tree uses the word branch, and the word branch uses the word tree. Likewise, the definition of the word stem uses the word leaf and the definition of leaf uses the word stem. In each case, you already have to know the meaning of one of the words to understand the definition of the other.

You can also see the problem of abstractness: The word tree is defined using the word plant, the word plant is defined using the word thing. How is thing defined? A typical definition is the following, which uses the word object:

thing, n. /θɪŋ/ an object that the language user cannot or does not want to name

A typical definition of object is the following:

object, n. /ˈɑb.d͡ʒɛkt/ something with a stable form that can be perceived by sight and touch and that is not alive

The definition of plant uses the word thing, but obviously not in the way that the word thing is defined — the “thing” in question has already been named plant, so it does not refer to something “that the language user cannot or does not want to name”. It also does not refer to an “object”, as objects are defined as ‘not alive’, so a ‘living thing’ would be a contradiction.

Instead, thing is used in the way that we have used the word entity at various points in the book. Many dictionaries use the word thing to define entity, which would lead us back to the problem just mentioned, but it can be defined without this word:

entity, n. /ˈɛn.tɪ.ti/ something that exists separately of and can be distinguished from other parts of the world

So, we could replace thing with entity in the defintion of plant, but this presents another problem: the definition for entity is so abstract that it can only be understood in terms of concrete examples: we have to know its extension — which contains, among other things, people, animals, plants, natural and artifical objects, emotions, ideas, etc. — in order for this definition to make any sense at all. In other words, it adds nothing to the definition of plant (or any other entity) that we do not already know.

The same problems exist if, instead of using dictionary definitions, we define words in terms of lists of properties, as we have also done above, for example, when stating the meaning of tree as ‘is a plant’, ‘is tall’, ‘is woody’, ‘has a single stem’, ‘has branches’, ‘has leaves’. Such a list format is better than a dictionary definition in that it forces us to think more rigorously about the properties that belong in the intension of a word, but the two are essentially just different ways of representing information — we can easily paraphrase a dictionary definition as a list of properties or vice versa.

Subsection Potential solutions to circularity and abstractness

There are two ways of dealing with the problems we just laid out. One would be to simply accept it. To repeat: when we are describing the meaning of a word, we are using language to describe commonalities of the mental experiences that humans have when interacting — or thinking about interacting — with one or more of its referents and the relations between referents. It would be surprising if language allowed us to do so in a way that is free of circularities and free of complex relationships between more abstract and more concrete meanings. Since as linguists we are describing the meaning of linguistic expressions for humans, not for aliens or robots, we can rely on the assumption that those humans will somehow make sense of these descriptions. Most of the time, the problems of circularity and abstractness do not cause great problems when discussing meaning, as you will see throughout the remainder of the book.

A second, more principled way of dealing with the problems discussed here would be to come up with a restricted set of expressions that cannot and do not need to be further defined but that can be used to define all other linguistic signs — atoms of meaning, so to speak. This has been attempted repeatedly, more or less systematically.

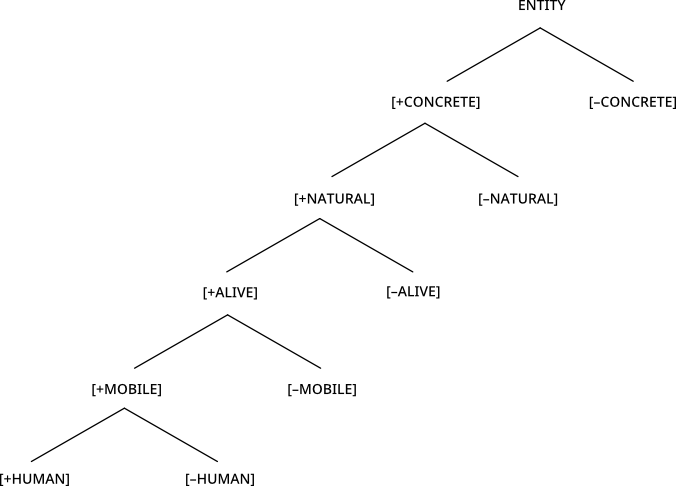

One such attempt that you will occasionally see is the idea of semantic features (or semantic components) — a restricted set of general hierarchically structured concepts. The idea is that word meanings can be defined as bundles of semantic features that are present or absent. The set of features should be as small as possible, so it would have to contain concepts that are useful the defintion of many words, but it should be large enough to yield a taxonomy of all word meanings in a given language, and the features themselves should be as simple as possible — ideally, they should not themselves need to be defined.

The idea is attractive, but extremely difficult to put into practice. Consider the hierarchy of features we would need to define a small portion of words from the letter B of a dictionary: bear (the animal), belief, birch, boat, boulder, and boy. All of them are entities in the sense of the term discussed above, so [+ENTITY] would be the first feature we would posit (this distinguishes the referents of these words from relations, events, etc.). A major distinction, and one that is likely to be useful for many other words, is that between entities that are CONCRETE (can be seen and touched, like bear, birch, boat, boulder, boy) and those that are not (like belief). Within the former, we would want to distinguish between entities that are NATURAL (part of nature, like bear, birch, boulder and boy), and those that are not (like boat). Within the natural concrete entities, we would want to distinguish between those that are potentially ALIVE (bear, birch, boy), and those that are not (boulder). Within the former, we would want to distinguish between entities that are MOBILE (bear, boy) and those that are not (birch). Finally, we would want to distinguish between those that are HUMAN (boy) and those that are not (bear).

This gives us the taxonomy of features shown in Figure 3.3.1.

A branching-tree representation of the distinctions made in the text.

The taxonomy allows us to distinguish the six words in question, but only as long as we do not add any additional words. Note that so far, it actually only distinguishes the meaning of the very general expressions human, animal, plant, natural object, artificial object (artefact), and abstract entity. We need to posit additional features to distinguish our six words from other words that fall under these general expressions.

For example, the word boy would have the features [+CONCRETE, +NATURAL, +ALIVE, +MOBILE, +HUMAN], but it would share these features with all other words for human beings. To distinguish it from girl, we would have to add the feature [+MALE] or [–FEMALE], depending on which of these we consider basic. To distinguish it from man, we would have to add the feature [–ADULT]. Thus, boy would be defined as [+CONCRETE, +NATURAL, +ALIVE, +MOBILE, +HUMAN, –FEMALE, –ADULT].

Question 3.3.2.

So far, things look good — the features we have posited are useful in distinguishing and defining many different meanings, they are hierarchically organized, they seem conceptually very basic — one could argue that they are “semantic atoms”. This changes when we attempt to define birch. So far, it has the features [+CONCRETE, +NATURAL, +ALIVE, –MOBILE], but it shares these with all other plants and funghi. We would need to add the kinds of features we have used above to define trees — features like [± LEAVES], [± SINGLE STEM], etc. These no longer fit the criteria that semantic features would fulfil: they are not useful in defining many words except for words for trees and shrubs, and they certainly do not look like semantic atoms. On the contrary, they are highly complex concepts whose meaning presumably consists of complex bundles of features.

These problems will only multiply if you seriously attempt to define the other words on our list.

Question 3.3.4.

Think about what features you would have to posit to distinguish bears from other animals, boats from other artefacts, boulders from other natural objects and beliefs from other abstract entities. How many of the features you have to posit seem plausible candidates for semantic atoms?

Given these problems, you will not be surprised to learn that nobody has ever managed to create a feature hierarchy for a substantial portion of the vocabulary of any language, and that most linguists have abandon the idea that the meaning of words can be described exhaustively in terms of semantically simple and general features. However, many linguists believe that there are some features of this kind that are useful when modeling meaning, because they pick out aspects of a word’s intension that are relevant to rules that combine words into larger units. We will discuss this idea briefly in Chapter 8.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Written by Anatol Stefanowitsch