Syllabify the word emblem. There are three consonants [mbl] in the middle of this word, so there are four logical possibilities for how they could be distributed between the coda of the first syllable and the onset of the second: 1) all consonants could belong to the coda of the first syllable, 2) all consonants could belong to the onset of the second syllable, 3) the [m] could belong to the coda of the first and the [bl] to the onset of the second syllable, or 4) the [mb] could belong to the coda of the first and the [l] to the onset of the second syllable. Which of these solutions is right according to the maximal onset principle?

Section 5.7 Syllables

The form of a spoken-language sign can be described as a sequence of phones. These sequences can vary in length: the form of some words consists of a single phone, as in awe (/ɑ/ in American English, /ɔː/ in British English), but most words consist of longer sequences, for example, [bæt] bat, [kʊkuː] cuckoo, [ɪnstɹəmənt] instrument or [ɹiːpɹɪstɪneɪʃən] repristination.

These sequences are not just flat strings of phones: they are organized into an intermediate structure called syllable.

Subsection What are syllables

You all know how to identify syllables intuitively: when you say a word like instrument slowly, it will sound something like this: [ɪn] (short pause) [strə] (short pause) [mənt]. In linguistics, syllables are often represented by the Greek letter σ (sigma). In a transcription, the boundaries between syllables are indicated with a period: [ɪn.strə.mənt]. Note that syllable boundaries are only marked between syllables, not at the beginning of the first syllable or the end of the last syllable.

A syllable consists of at least one phone, referred to as the nucleus. This is typically a vowel, as in the three syllables in [ɪn.strə.mənt], but it can sometimes be a consonant. Languages differ with respect to which consonants they allow to function as a nucleus (see further Section 6.5); in English, as in many languages, liquids ([l], [ɹ]) and nasals ([m], [n] or [ŋ]) can serve this function, as in the second syllable of the words [ˈbɑt.l̩] bottle or [’bʌt.n̩] button. Note that consonants that serve as the nucleus of a syllable are transcribed with a little tick mark below the IPA character.

The nucleus may be preceded and/or followed by one or more consonants. These are referred to as the margins. A margin with only one phone is called simple, and a margin with two or more phones is called complex. More specifically, the left margin is called the onset, the right margin is called the coda. Some linguists assume a hierarchical organization, such that the nucleus and the coda form an intermediate unit referred to as the rime. A syllable with no coda, such as a CV or V syllable, like English [si:] see and [ɑ] awe, is often referred to as an open syllable, while a syllable with a coda, such as CVC or VC, like English [hæt] hat and [i:t] eat, is a closed syllable. A syllable with no onset, such as V or VC, like English [ɑ] awe and [i:t] eat, is called onsetless. There is no special term for a syllable with an onset.

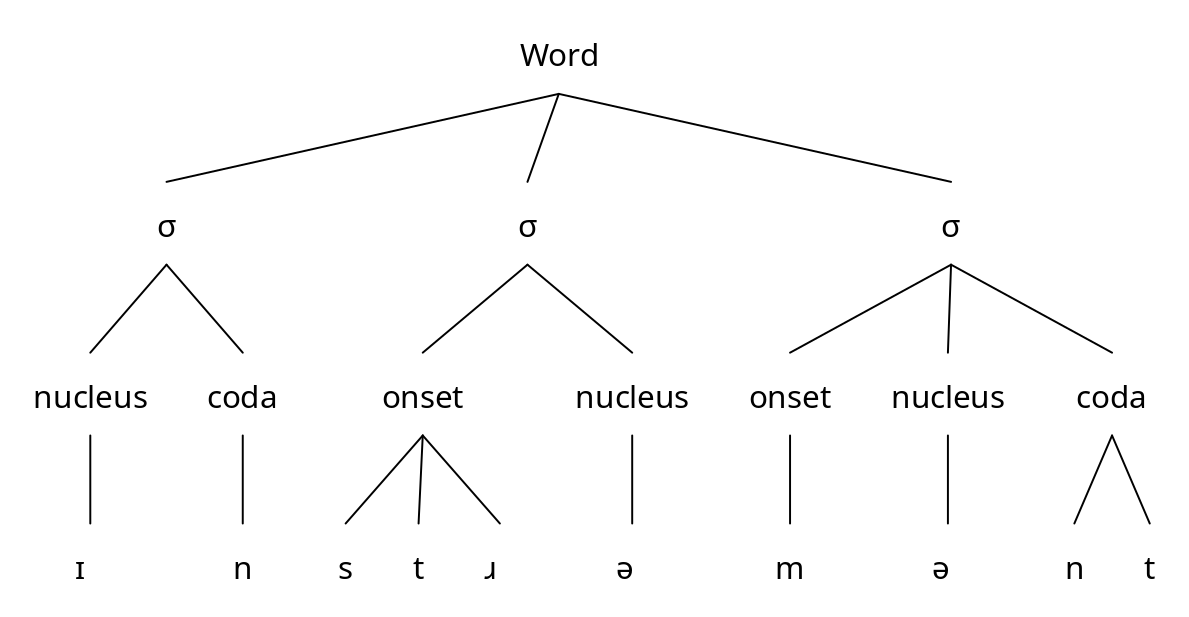

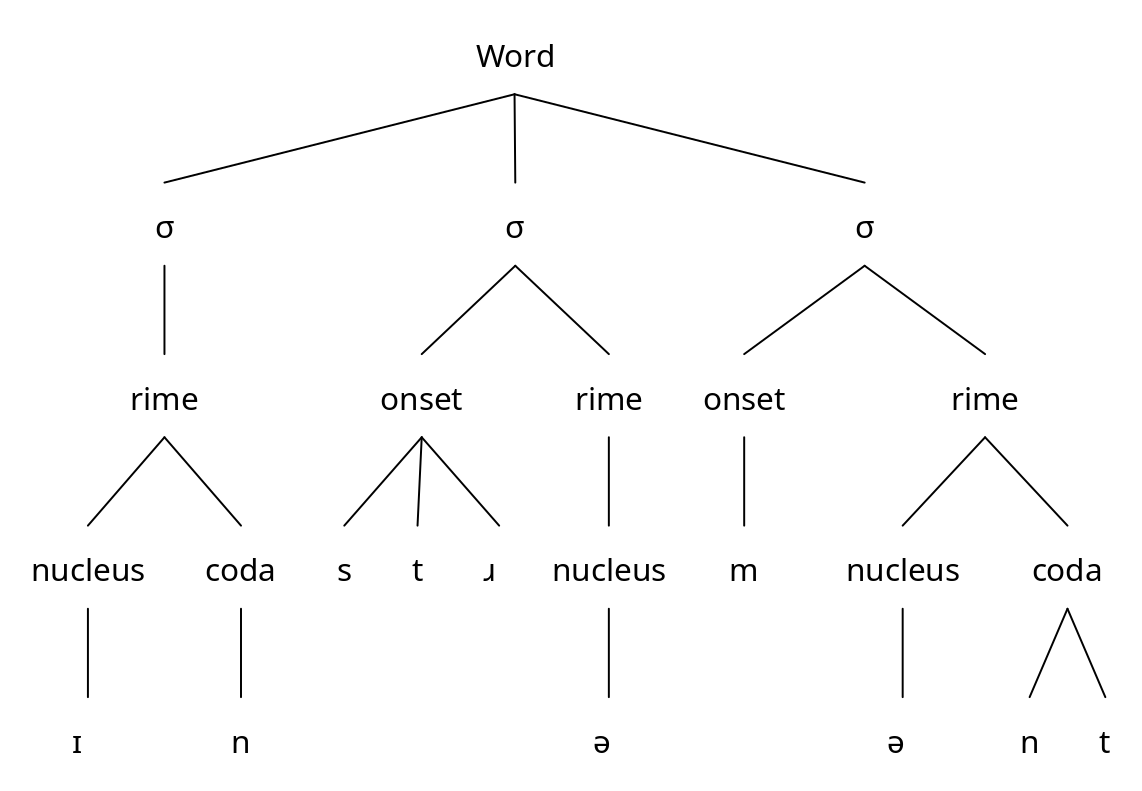

We can show syllable structure graphically as a tree diagram, as in Figure 5.7.1 (without a rime) and Figure 5.7.2 (with a rime).

Tree diagram showing the syllable structure of the word instrument.

A tree diagram of the syllable structure of the word instrument, including rimes.

As an alternative to tree diagrams, syllable structure can be notated using CV-notation, with one C for each phone in the margins and one V for each phone in the nucleus (note that V is typically used in the nucleus even if it represents a syllabic consonant). Thus, the syllable structure of [ɪn.stɹə.mənt] can be represented as VC.CCCV.CVCC.

Subsection The maximal onset principle

If a word consists of a single syllable, it is easy to determine which consonants belong to the onset (all consonants that precede the vowel) and which belong to the coda (all consonants that follow the vowel). But if a word consists of two or more syllables, things get more complicated: speakers (and we, as analysts) have to decide which of the consonants between two syllable nuclei belong to the coda of the first syllable and which belong to the onset of the second syllable. Why do we syllabify instrument as [ɪn.strə.mənt], and not, for example, as [ɪnst.rəm.ənt]?

There is a principle that seems to operate in most languages, called the maximal onset principle. As its name suggests, it states that onsets should be maximized: if it is possible for a consonant to occur in the onset, it should. By “possible”, we mean roughly that, if we add a consonant to the onset of a syllable, that onset could also occur at the beginning of an isolated syllable or at the beginning of a word. Consider the second syllable of the word instrument: The nucleus is the [ə]. If we add the preceding [ɹ], the resulting syllable [ɹə] could occur in isolation or at the beginning of a word (for example, repeat); if we add the preceding [t], the resulting syllable [tɹə] could occur in isolation or at the beginning of word (for example, tremendous); if we add the preceding [s], the resulting syllable [stɹə] could occur in isolation or at the beginning of word (for example, strategic); but if we add the preceding [n], the resulting string [nstɹə] could not occur in isolation, and no word in English can begin with this sequence. Thus, [stɹ] is the maximal onset possible.

Let’s look at another example to illustrate the idea that onsets are greedy. Consider the word ugly. The two vowels [ʌ] and [i] form the two nuclei of the syllables; there’s no onset for the first syllable, and no coda for the second syllable. So there are three logical possibilities for the consonants [ɡl] — they could both belong to the coda of the first syllable; they could both belong to the onset of the second syllable; or they could be divided up between the two. The onset is greedy, so it wants to take as many consonants as it can. We know that [ɡl] is a possible onset in English, because there are lots of words that start with [ɡl], like glue, glass, glamour. Because [ɡl] is a possible onset in English, the onset of the second syllable takes both consonants, leaving nothing for the coda of the first.

Question 5.7.3.

Subsection Crosslinguistic patterns in spoken language syllable types

Spoken languages generally prefer onsets and disprefer codas. This means that it is common for languages to require onsets, but it seems like there are no languages that require codas. Conversely, it is common for languages to prohibit codas, but there are no languages that prohibit onsets. These possibilities can be notated using parentheses to show what is allowed but not required. So we find languages whose syllables are all of the type CV(C); that is, they have a required onset and nucleus but an optional coda. However, there seem to be no mirror image languages whose syllables can all be classified as (C)VC, with an optional onset but a required nucleus and coda.

In addition, spoken languages generally prefer simple margins to complex margins. Thus, in languages that allow codas, some allow only simple codas and prohibit complex codas; if a language allows complex codas, it also allows simple codas. Similarly for onsets: some languages prohibit complex onsets, and if a language allows complex onsets, it also allows simple onsets.

There seems to be no strong relationship between complex onsets and complex codas: some languages allow complex onsets, some allow complex codas, some allow both, and some allow neither. All together, these trends give us a range of possible languages based on what kinds of syllable structures they allow and prohibit.

English has a relatively complex syllable structure which can be notated as (CCC)V(CCCC), meaning that a vowel (nucleus, to be exact) is minimally required, with zero to three consonants in the onset, and zero to four consonants in the coda. Onset clusters with three consonants are made up of either [spr], [spl] or [str], as in [spɹɪŋ] spring, [splæʃ] splash or [stɹiːt] street. Coda clusters with four consonants typically end in [s], like in [tɛksts] texts and [pɹɑmpts] prompts, or in [t], like in [ɡlɪmpst] glimpsed, although they are rare overall.

As mentioned, spoken languages prefer simple syllables, so the syllable structure of many languages is much simpler. For example, Turkish doesn’t allow any consonant clusters in the onset, and it rarely allows consonant clusters in the coda. This can be notated as (C)V(CC). When Turkish borrows words from languages with more complex syllable structure, such as plan ’plan’ from French or tren ’train’ from English, Turkish speakers add vowels between the consonants in the onset clusters, breaking them up into separate syllables with simple onsets: [pi.lan] and [ti.rɛn].

Languages with even simpler syllable structures are rare. One of them is Hawaiian, which has a strict (C)V pattern (or (C)V(V), if diphthongs are treated as sequences of two vowels). This means that all syllables are open (there are no codas), and onsets can contain one consonant at the most.

This means that every syllable must end in a vowel, and consonant clusters are not permitted. Examples are [ˈhoː.kuː ˈʔɐe̯.ʔə] hōkū ʻaeʻa ’planet’ and [ɐ.ʔu ˈkuː] aʻu kū ’swordfish’. This restriction also applies to words borrowed from other languages, with the result that they often do not look very similar to the original word. Examples are [ka.me.piu.la] kamepiula from English computer or [pa.naˈkoː] panakō from English bank.

To sum up, syllables are sequences of phones that have internal structure: every syllable has at least a nucleus, typically a vowel. In addition, it may have an onset and/or a coda, each consisting of one or more consonants. Onsets are greedy: they will incorporate as many consonants as possible within the constraints of a particular language. We will come back to these constraints at the end of Chapter 6.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adapted from Catherine Anderson, Bronwyn Bjorkman, Derek Denis, Julianne Doner, Margaret Grant, Nathan Sanders, and Ai Taniguchi, Essentials of Linguistics. 2nd ed.; section on the “Maximal Onset Priciple” by Elif Kara; edits and rewrites by Anatol Stefanowitsch.