Use this type of representation, called a Venn diagram, to illustrate the compositional meaning of the following phrases: red bus, dead tree, tropical timber, Noah’s dog.

Section 4.4 Compositionality and idiomaticity

We have discussed the meaning of individual words and of sentences. But how do we get from one to the other?

Subsection Compositionality

Language users have to learn individual linguistic signs one by one — since they are arbitrary pairings of form and meaning, we cannot usually predict the meaning of a word we do not know. Look at the words in (1a-e) show:

Even if you are a highly fluent speaker of English, you likely do not know some (or even any) of these words. If you had to guess their meaning, you might try to look for smaller parts that are familiar to you — perhaps age and last in (1a), fast in (1b), -ate in (1b) and (1e) or -ic in (1d). Since words are often made up of smaller parts (see further Section 7.2), this strategy can sometimes work, but it would not help you here: an agelast is a person without a sense of humour, a fastigate tree or shrub is one whose branches grow almost parallel to its stem, to fratch means “to disagree or quarrel”, peristeronic means “related to pigeons” and “vulpinate” means to “behave like a fox”.

With larger units of language (phrases and sentences), things are different. Look at the following two sentences:

- (2a)

- The peristeronic agelast who likes to vulpinate is fratching about the fastigate tree again.

- (2b)

- Aylin bought a vintage red ball for her niece’s third birthday.

Unless you have read this book before, you have never encountered either of them — even the one in (2b) that does not contain any rare words. Nevertheless, you can easily determine their meaning. This is because the meaning of sentences is composed of the meaning of the individual words they contain. This is referred to as the principle of compositionality. Without such a principle, we would have to learn the meaning of individual sentences in the same way we have to learn the meaning of individual words, heavily restricting what we could talk about. With such a principle, we can communicate infinitely many different things.

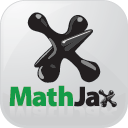

The basic idea behind the principle of compositionality is simple: when we combine words into larger units using grammatical rules (), we simultaneously combine their meanings. We will come back to the formal side to this process in Chapter 8. Take the phrase red ball from (2b). The intension of ball includes the features “is an object”, “is spherical”, “is for playing” (and probably some others); its extension is the set of all entities with these features. The intension of red is the feature is red; its extension is the set of all entities with this feature — for example, cherries, foxes, red roses, London buses. The intension of the phrase red ball is the combination of the features of red and ball, its extension is the intersection of the set of balls and the set of red things. Figure 4.4.1 illustrates this.

Two overlapping circles; the first one contains a green ball, a yellow ball, a blue ball and a red ball (all with white polka dots), the second circle contains a bunch of cherries, a red rose, a fox, a London bus, and the red ball. The circles are labeled with the semantic features mentioned in the text.

Or, to put it another way: The statement “x is a red ball” is true if it is true that “x is a ball” and “x is red”.

Question 4.4.2.

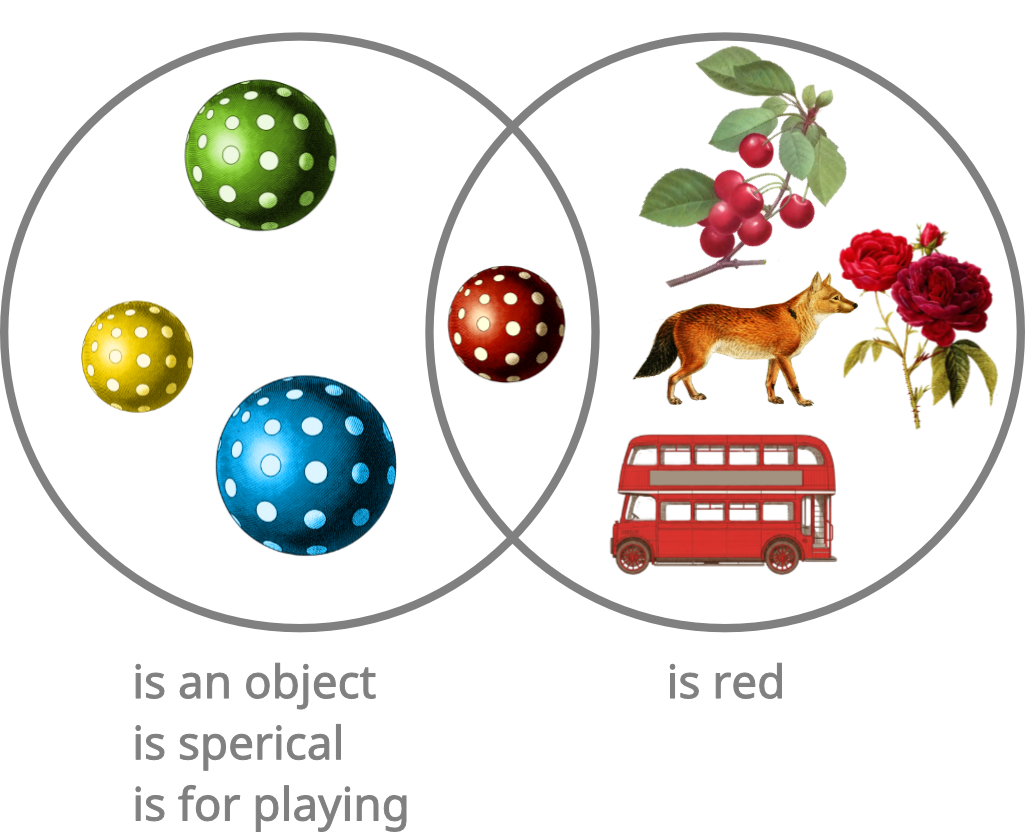

This principle can be applied to other types of phrases and to whole sentences. For example, the meaning of the sentence Aylin bought a ball is the intersection of the set of referents involved in a buying event (e.g. Noah will buy a bike, Zoe is buying milk, …), the set of events involving Aylin doing something (e.g. Aylin rides bikes, Aylin carried a book, …), and the set of events involving something being done to balls (e.g. Zoe drew a ball, Barabara will kick the ball, …). Figure Figure 4.4.3 illustrates this.

Three overlapping circles; the first one is labeled BUY(x, y), the second one is labeled PRED(A,…), the third one is labeled PRED(…, BALL). The intersection of all three circles contains BUY(AYLIN, BALL), the intersection of the first and second circle contains BUY(A, BIKE), the intersection of the first and third circle contains BUY(N, BALL), the intersection of the second and third circle contains CARRY(A, BALL); the remainder of the first circle contains BUY(N. BIKE), BUY(N, DOG), BUY(Z. MILK), the remainder of the second circle contains RIDE(A, BIKE), FELL(A, TREE), CARRY(A, BOOK), the remainder of the third circle contains DRAW(Z. BALL), THROW(B, BALL), KICK(B, BALL).

Question 4.4.4.

Use this type of representation to illustrate the compositional meaning of one the following sentences: Zoe felled a tree, Aylin gave Seyda a ball., Barbara adopted Noah.

Subsection Idiomaticity

While the principle of compositionality is crucial for the proper functioning of human languages, there is a class of linguistic expressions that violate this principle. Look at example (3):

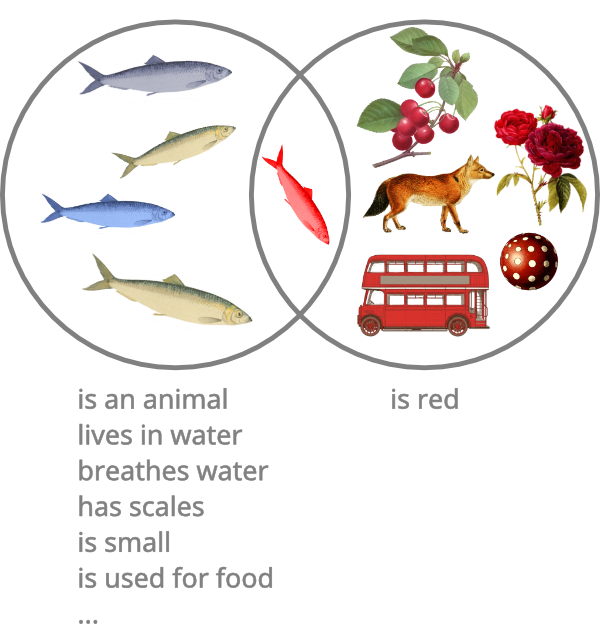

If the phrase red herring were compositional, it should refer to the intersection of the set of entities that are red and the set of entities that are herrings (i.e., entities whose intension contains features such as “is an animal”, “lives in water”, “is small”, “is used for food”, etc.), as shown in Figure 4.4.5.

Two overlapping circles; the first one contains a grey herring, a blue herring, two yellowish herrings and a red herring, the second circle contains a bunch of cherries, a red rose, a fox, a London bus, a red ball and the red herring. The circles are labeled with the semantic features mentioned in the text.

And of course, that is a possible meaning of this phrase — if we were to paint a herring red, for example, that is how we would refer to the result. However, the phrase is almost exclusively used as shown in (3), where it means “something that is intended to distract people from a more relevant topic” — example (3) means that Zoe thinks the idea of companies paying for the right to pollute the environment is intended to distract from something (such as the question of how such pollution can be avoided in the first place).

If we wanted to analyze this expression as compositional, we would have to take one of two approaches. First, we could point out that red herring refers to herring that has been soaked in brine and strongly smoked, giving its flesh a slightly reddish color, and that there are reports that such herrings were used to train dogs for fox hunting, such that they had to learn to ignore the scent of the herring and follow the fox instead. We could then argue that language users transfer this situation to more abstract domains when using the expression red herring. The problem with this idea is that it requires language users to be aware of this (potential) origin of the expression, but most people using the expression have probably never heard of this story.

Second, we could posit special senses of the word red and herring. We could claim that the adjective red has a special sense “intended to be distracting” and that the noun herring has a special sense “information”. In this way, we could argue that the extension of red herring is the intersection of things that are intended to be distracting and things that are information. The problem with this idea, however, is that these word senses never seem to occur outside of this particular expression. We cannot say, for example, The spies played red music, meaning “music intended to distract opponents from their conversation” or I need more herring, meaning “I need more information”.

Thus, the more obvious way of dealing with such expressions is to admit that there are expressions that are not compositional and that have to be learned as a whole. Such expressions are called idioms — the principle of compositionality is limited by the phenomenon of idiomaticity.

Question 4.4.6.

Determine which of the following expressions can be idiomatic and which are always compositional (use a dictionary if you are unsure): cold turkey, cold pork, bitter cabbage, bitter pill, red banner, red flag, bright idea, bright light.

Idiomaticity and compositionality are two endpoints on a scale rather than fully discrete categories — many expressions fall somewhere in-between the two extremes. Look at the following sentences containing the verb bite:

- (4a)

- Laika tried to bite the pizza delivery man again.

- (4b)

- Zoe wanted to complain to her boss but Noah told her not to bite the hand that feeds her.

- (4c)

- Aylin secretly wished that the president would bite the dust already.

- (4d)

- Noah didn’t feel like studying so Aylin told him to just bite the bullet.

Example (4a) is a compositional use of the verb bite meaning “use one’s teeth to cut into” — its extension is the intersection of biting events, events involving Laika doing something and events of someone doing something to the pizza delivery man. In contrast, examples (4b-d) are idiomatic uses — there are no teeth involved in any of the events described. However, they differ in how difficult they are to interpret. Even someone unfamiliar with the expression in (4b) can make a reasonable guess at what Noah said to Zoe — that she should not antagonize her boss, because he might fire her. The image of someone (a dog or cat, perhaps) biting the hand of the person feeding them is immediately obvious, unlike that of dogs following the scent of a heavily smoked red herring. The expression in (4c) is a little more difficult to interpret for language users who have never heard it. One might think that it refers to an unpleasant experience, such as eating lettuce that has not been washed properly and biting on sand or earth, or that it refers to a situation where someone cleans their apartment thoroughly, attacking the dust ferociously. Once we know that it means “to die”, however, we can easily picture someone falling over dead and landing with their face in the dust, so we understand the motivation for the idiom. Finally, language users who are unfamiliar with the expression bite the bullet will not be able to guess what it means — a plausible interpretation would be “to die” again, based on the image of someone getting shot in the mouth. Even when we learn that it actually means “to accept an unpleasant task or situation”, it is unclear why this should be the case (the story goes that the idiom originates in the practice of letting soldiers bite on a lead bullet while performing surgery on them without anesthesia).

Idioms whose meaning we can guess with reasonable accuracy are sometimes referred to as idioms of encoding — they cannot be constructed using the general rules of language and following the principle of compositionality, but if we encounter them, we can understand them. Idioms whose meaning cannot be guessed — true idioms — are sometimes called idioms of decoding.

Question 4.4.7.

Look at the following expressions and determine whether they are idioms of encoding or idioms of decoding: kick the shit out of someone, kick the bucket, bear the responsibility, bear the brunt, shoot the breeze, shoot the messenger, pop pills, pop the question, between a rock and a hard place, between the devil and the deep blue sea, outside the box, outside the law.