Section 7.2 Types of morphemes

In studying the internal structure of words, we must distinguish different types of morphemes along a number of dimensions. Look at the following words, paying attention to their constituent elements:

Subsection Free and bound morphemes

The first distinction is that between morphemes that can stand alone, like {/lɑː/} law, and those that cannot, like {‑/ləs/} in lawless. The former are called free morphemes, the latter are called bound morphemes. Polymorphemic words may consist of several free morphemes, like /ˈaʊt.lɑː/ outlaw, which consists of the preposition {/aʊt/} and the noun {/lɑː/} or /ˈlɑː.mən/ lawman, which consists of the nouns {/ˈlɑː/} law and {/mæn/} man (the latter is pronounced with a schwa in lawman because it is unstressed). Such words are called compound words (or simply compound). Polymorphemic words can also consist of a free morpheme and one or more bound morphemes, like /ˈlɑː.ləs/ lawless or /lɑːz/ laws. In this case, the free morpheme — {/lɑː/} law — is called the root, the bound morphemes — {‑/ləs/} or {‑/z/} — are called affixes. Depending on their position in the word, there are more specific labels: affixes that attach to the beginning are called prefix, affixes are attached to the end are called suffix (we will see more types of affixes in a moment). Affixes can also attach to words that are already polymorphemic — like {/ʌn/‑}, which attaches to /ˈlɑː.fəl/ lawful, which itself consists of the root {/ˈlɑː/} and the affix {-fəl/} ‑ful. A more general term for the thing an affix attaches to is base — bases can be simple, in which case they are also roots, or complex, in which case they are not.

Most affixes attach only to bases of a particular word class, or, in a few cases, a small set of word classes. For example, the prefix {un‑} only attaches to adjectives, so we get unlawful, but not *unlaw. You may think that verbs like undo, unlock, unfold, unravel, unveil etc. contradict this claim, as in all these cases it looks as though the prefix {un‑} attaches to verbal bases. However, we are actually dealing with two different affixes here: {un‑}₁ ‘not’, which attaches to adjectives, and {un‑}₂ ‘reverse’, which attaches to verbs: unlawful means ‘not lawful’ (and likewise for the other adjectives), but ‘undo’ does not mean ‘not do’, it means ‘reverse what was done earlier’ (and likewise for the other verbs).

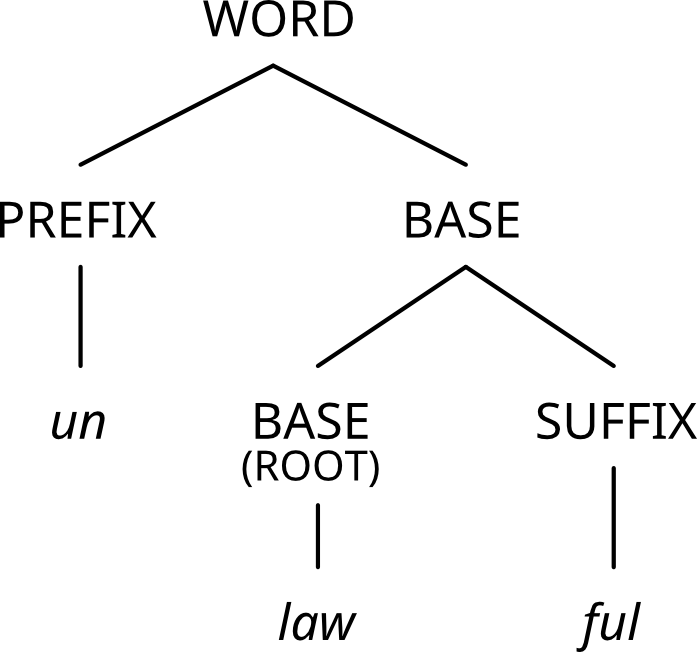

We can represent the structure of complex words using tree diagrams like the one shown in Figure 7.2.1

[WORD [PREFIX un] [BASE [BASE law] [SUFFIX ful]]

The distinction between bound and free morphemes is usually very clear, but there are morphemes that fall somewhere in-between. An example is {/laɪk/} in /ˈaʊt.lɑːlaɪk/ outlaw-like (e.g. She had an outlaw-like appearance). The meaning of ‑like is still more or less identical to the meaning of the preposition like (as in Her appearance was like that of an outlaw), and the form is identical. One might think that they are, in fact, the same morpheme, and that outlaw-like is a compound. This would not only explain that they seem to have the same meaning, but it would also explain why like has secondary stress, which affixes do not. Note that we would not confuse the {‑less} in lawless with the less in There is less crime now that there is a new lawman in town: the meaning of the two morphemes is different ({less} means ‘not as much’ while {‑less} means ‘not having’), and the word less is pronounced /lɛs/ while the affix is pronounced /ləs/. On the other hand, note that outlaw-like does not behave like a compound: compounds typically have the same word class as their second part, but outlaw-like is an adjective, while like is a preposition. Morphemes that have this type of ambiguity between free and bound are sometimes referred to as affixoids.

The distinction between monomorphemic and polymorphemic words is also usually clear, but here, too, there are borderline cases. Take the example of the Japanese loan word /ˌtɛrɪˈjɑːki/ teriyaki. If you like Japanese food, you might have noticed that the sequence [jɑːki] yaki occurs not only in teriyaki, but also in teppanyaki, takoyaki and yakitori (to name just a few). You might therefore suspect that these words consist of more than one morpheme and that yaki means the same thing in all of them. And as far as Japanese is concerned, you would be right: yaki (焼き) roughly means ‘grilled’, ‘fried’ or ‘broiled’ in Japanese, teri (照り) means ‘shine’, teppan (鉄板) means ‘iron plate’, tako (たこ) means ‘octopus’ and tori (鳥) means ‘bird’. But while this is relevant for the analysis of Japanese, it is not relevant to English: from the perspective of English, teriyaki, teppanyaki, takoyaki and yakitori are simple morphemes.

However, when a sufficient number of loanwords enter a language, the language community may at some point connect the form and meaning. Consider the following loanwords from Latin: circumstance, circumvent, circumference, circumscribe, circumspect, circumcise, circumnavigate, circumlocution, circumflex. These are just a few of the many Latin loanwords containing the form circum, and the meaning of all of these words includes something like AROUND. In Latin, it is the adverbial accusative of the word circus ‘circle, ring’. In English, the first loanwords were likely treated as monomorphemic by speakers, just like teriyaki, teppanyaki etc. But at some point, a sufficiently large number of speakers recognized the systematic form-meaning relationship and began to treat {circum‑} as a morpheme with the meaning ‘around’. We know this, because words like circumantarctic, circumpolar, circumlunar, circumsolar, and circumterrestrial were formed in English, meaning ‘around the antarctic, pole, moon, sun, earth’ respectively. In other words, what speakers treat as a morpheme may change in the course of the history of a language.

Subsection Types of affixes

Note that affixes differ in their relationship to the base. In English, there are only the two types of affixes we have already mentioned: prefixes and suffixes, but other languages have other types of affixes.

Prefixes attach to the beginning of a base: {un‑} in unlawful (or unusual, unable, unlikely, unknown, etc.) is a prefix.

Suffixes attach to the end of a base: {‑ful} in lawful (or beautiful, successful, powerful, wonderful, useful, etc.) and {‑less} in lawless (or endless, countless, useless, helpless, harmless etc.) are suffixes.

Circumfixes, also known as discontinuous affixes, are affixes that come in two parts with a single, unified function. They attach to the beginning and the end of a base simultaneously. This happens, for example, in German past participles:

The affix in these cases is {ge‑ … ‑en}.

Note that, in linguistics, examples from languages other than the one in which a book or research paper is written are presented in the three-line format introduced here:

-

the first line gives the example in the original language, either as a phonetic or phonemic transcription or in the standard orthography of the respective language; for polymorphemic words, hyphens are inserted at the morpheme boundaries;

-

the second line gives the meaning or function of each morpheme (this is called a gloss)

-

the third line gives an idiomatic translation of the whole example into the language the author is writing in.

Morpheme-by-morpheme glosses are not standardized in linguistics, but many linguists nowadays follow the Leipzig Glossing Rules, which you can find here: https://www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/resources/glossing-rules.php.

1

www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/resources/glossing-rules.php

Infixes are affixes that appear within another morpheme. For example, in Tagalog (a language with about 24 million speakers, most of them in the Philippines) the infix {‑um‑} is inserted after the first consonant of the base to which it attaches. This infix expresses perfective aspect for verbs. Perfective aspect indicates completed action, usually translated with the English simple past:

Subsection Clitics

There is another type of bound morpheme that looks like an affix at first sight, but on closer inspection behaves very differently. Consider the following expressions, which all contain the morpheme {’s POSSESSIVE}:

In examples (4a) and (4b), the morpheme looks as though it attaches to the proper name Aylin, the way we would expect it from a suffix — the plural would attach in the same way: I know two Aylins, These are my neighbors. However, in (4c), it seems to attach to the wrong noun: the dog belongs to the neighbor, not to the road! A suffix would attach to the right noun: These are my neighbors across the road, not *These are my neighbor across the roads. In (4d) and (4e), the possessive {’s} does not even attach to a noun — in (d) it attaches to a spatial adverb, in (4e) to a verb. Again, a suffix would not do this: These are my neighbors three doors down, not *These are my neighbor three doors downs and These guys I know, not *These guy I knows.

So, what is going on here? In fact, the morpheme {’s} does not attach to an individual word at all, but to the expressions [Aylin], [my neighbor], [my neighbor across the road], [my neighbor three doors down] and [this guy I know]. As we will learn in the next chapter, these expressions are referred to as noun phrases. Morphemes that attach to phrases rather than words are called clitics. To distinguish them from affixes, we use an equal sign instead of a hyphen to show on which side of a phrase they attach, so the proper way to notate the English possessive is {=’s} or {=/z/}.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adapted from Catherine Anderson, Bronwyn Bjorkman, Derek Denis, Julianne Doner, Margaret Grant, Nathan Sanders, and Ai Taniguchi, Essentials of Linguistics. 2nd ed. by Kirsten Middeke, rewriting and additional section on Clitics by Anatol Stefanowitsch.