Think of other examples of words (or larger expressions) with different senses but the same reference.

Section 2.3 More on meaning

In Section 2.1, we discussed the fact that the meaning of a word is a mental representation of our knowledge about a particular entity. And clearly, we use language much of the time to talk about such entities in an abstract way. Imagine that Aylin and Zoe are roommates in a city with lots of street trees. It hasn’t rained in weeks and they have noticed that the trees in front of their apartment building seem to be in bad shape. They go online to research ways to nurture trees through a drought. They find a website that says the following:

- (1)

- Young trees need a lot of water (at least 50 liters per week). Mature trees need to be watered about once a month during an extended drought, and it is important to make sure that the water reaches the roots. The best way of achieving this is by using drip irrigation, where you lay a water hose with holes in it around the roots and let the water soak into the ground slowly.

Whoever wrote this passage is talking about trees in general, not any particular tree, and certainly not the trees in front of Aylin’s and Zoe’s apartment. While they are reading, they also do not think about these (or any other) specific trees. They understand what they read because they know the meaning of words like tree, root, water, liter, month, hose etc. independently of any actual trees, roots, water, etc.

But clearly, we also use language to talk about the world and the specific entities contained in it. Imagine that after having read up on watering street trees in general, Aylin and Zoe take a walk around the neigbourhood and look at specific trees. Aylin could say something like This tree here will be easy to water, but our hose is not long enough to water the tree over there. Now, she is using the words tree and hose to talk about two specific trees and a specific gardening hose — she is using the words to refer to specific real-world instances of the concepts TREE and HOSE.

Subsection Two kinds of meaning

When we talk about the meaning of a linguistic expression, there are two possible ways in which this word can be interpreted: it could refer to the concept — as in What does the word tree mean? — or it could refer to a specific entity corresponding to that concept — as in Which of the trees do you mean? To avoid confusion, linguists often refer to the concept associated with a particular word as the sense of that word, and the ability of speakers to apply the word to specific entities in the world as its reference (the entities themselves are referred to as potential referents of the word).

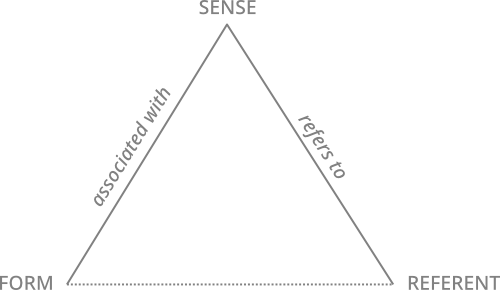

We can represent the relation between the form, sense and reference of a linguistic sign as shown in Figure 2.3.1 (simplifying a diagram first proposed by the linguist Charles Kay Ogden (1889–1957) and the literary critic Ivor Armstrong Richards, and using the terms introduced here).

A triangle with a solid line rising from the left to the center, and falling from the center to the left, with a dashed line connecting the endpoints. The lower left is labeled “FORM”, the top is labeled “SENSE”, the lower right is labeled “REFERENT”. The line connecting FORM and SENSE is labeled “associated with”, the line connecting SENSE and REFERENCE is labeled “refers to”

Once made, the distinction between sense and reference seems simple, but there is much more to it than first meets the eye.

First, two expressions with different senses may have the same reference. A famous example, introduced by the German philosopher Gottlieb Frege, are the expressions morning star and evening star. The sense of the first expression is something like ‘the brightest celestial body visible in the eastern sky after sunset’, the sense of the second expression is something like ‘the brightest celestial body visible in the western sky before sunrise’. It just so happens that in both cases, that body is the planet Venus, so both expressions refer to this planet. If this example seems a little boring to you, think of the different ways that Aylin’s and Zoe’s neigbours might refer to them after they start watering the trees outside their house. Say one neigbour calls them tree huggers, one calls them conservationists and one calls them nature-lovers. They are all doing the same thing on the level of reference — referring to two specific individuals. But they are doing very different things at the level of word sense — one is criticizing them, the other two are not, but they are attributing different motives to their actions.

Question 2.3.2.

Second, two expressions can have the same sense but different referents, depending on when, where and by whom they are used. For example, if a professor tells a colleague I have a meeting with the president, the colleague will assume that they mean the president of the university. In contrast, if the secretary of defense tells a colleague the same thing, the colleague will assume that they mean the president of the country. And of course, the precise referent of the word president will then depend on which university or which country we are talking about. Yet, the word president has the same sense in all cases — something like ‘the elected head of an institution’. Or think of a word that you use dozens of times each day: I. The sense of the word is ‘speaker of the current utterance’, which means that the reference is different for every single person who uses it!

Question 2.3.3.

Think of other examples of words (or larger expressions) with the same sense but different reference.

Third, there are expressions that have a sense but no reference. A textbook example is the word unicorn. We all know what it means — ‘a horse-like creature with a single horn on its forehead’. We can talk about unicorns, for example arguing whether they have wings, whether they can fly without wings or whether they cannot fly at all, discussing whether and how they can best be captured, what exactly their relationship to rainbows is, etc. All this in spite of the fact that — as far we know — unicorns do not exist and never have.

Question 2.3.4.

Think of other examples of words (or larger expressions) with a sense but no reference.

Fourth, there are expressions that have reference, but no sense. In fact, these are very common, you all have at least one: a name. The names of our two environmental activists, Aylin and Zoe, do not have a sense, even though Aylin might claim that her name means ‘one who belongs to the moon’ (ay means ‘moon’ in Turkish) and Zoe might claim that her name means ‘life’ (the Greek word for life is zoí (ζωή)). While these meanings may have played a role in the creation of these names at some point in the past, they do not play a role in the use of the names. Someone called Aylin does not belong to the moon, nor do we think they belong to the moon, nor would we know what it means to ‘belong to the moon’. We would keep referring to Zoe as Zoe even after her death. And we can use the names, and most of us do use these and other names, without knowing anything about their supposed original senses. That does not mean that such (real or imagined) senses do not play a role in name-giving, but that is a completely different question.

Question 2.3.5.

(a) Find out whether your own first name has (or is claimed to have) a “meaning”. Think about whether you identify with this meaning and why it is completely irrelevant to the use of the name whether you do so or not. (b) Think about last names (family names) in the languages you know: these are often derived from common nouns, as in the case of Smith, Baker or Brown in English. Sometimes, these words have potentially embarassing connotations, which may or may not be related to their etymology — for example, Assmann, Cobbledick or Titball. To what extent may such cases challenge the idea that names are meaningless?

Subsection Signs and speakers

While referring to entities and situations is the most important function of linguistic signs, humans use language for other reasons, too. Consider the word timber ‘wood for construction’ from Table 2.2.5 in the following examples:

- (1a)

- The increasing demand for timber resulted in rapid deforestation.

- (1b)

- Well shiver my timbers, if it isn’t Long John Silver!

- (1c)

- Timber!

Example (1a) might occur in a book about environmental issues, example (1b) in a dialogue from an adventure novel involving pirates (the expression shiver my timbers frequently occurs in R L Stevenson’s Treasure Island and in every pirate story since), and example (1c) is what lumberjacks used to shout in the US and Canada when they were cutting down a tree. In all three cases, the word timber refers to “wood used as construction material” (in 2b more specifically to the frames and ribs of a ship). But it is only in example (1a) that this referring function is the dominant function. In example (1b), the word forms part of an expression whose dominant function is the expression of surprise on the part of the speaker, and in example (1c) it is a warning to a potential hearer that a tree is falling.

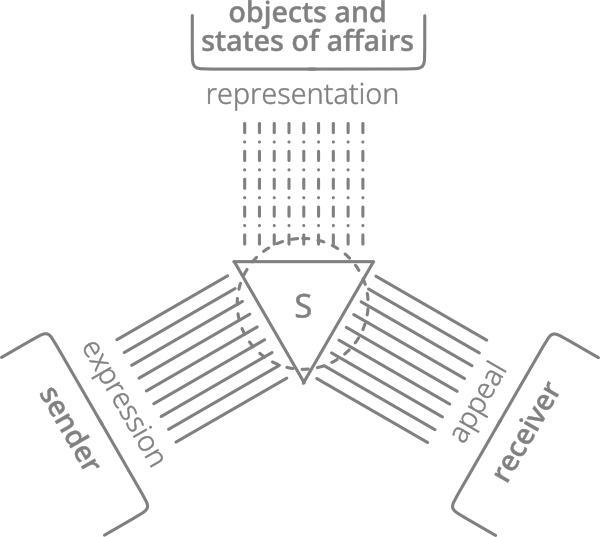

The latter two functions were first described by the German psychologist Karl Bühler (1879–1963), who called them expression and appeal. Unlike the referential function, which relates a sign to entities in the world, these two functions relate to the speaker and the hearer: the speaker may express something about themselves (in example (1b), the fact that they are surprised), and/or they may appeal to the hearer (in example (1c), to get out of the way of a falling tree). Bühler summarized his ideas in what he called the Organon (Classical Greek for “tool”) model of the linguistic sign (see Figure 2.3.6).

A triangle labeled S, with a circle superimposed that leaves the corners outside. A set of lines is radiating outward from each side of the triangle, leading to three boxes labeled "representation"/"objects and states of affairs", "expression"/"sender" and "appeal"/"recipient".

While most linguistic signs can be used in all three functions, there are signs that are dominantly (or even exclusively) expressive — for example, interjections like ouch (expressing pain), oh (expressing surprise), wow (expressing astonishment or admiration) or eww (expressing disgust). Likewise, there are signs that are dominantly (or exclusively) appellative — for example hey in American English or oi in British and Australian English (appeal to be noticed) or fuck off (appeal to leave).

Question 2.3.7.

Think of some utterances (not necessarily single words) with a dominant expressive or appellative function.

Bühler’s work was extended by the Russian linguist Roman Jakobson (1896–1982), who called the expressive function emotive and the appellative function conative, and added three more functions:

the phatic function, where language is used to establish and maintain human contact (e.g. greetings like hello or feedback signals like m-hm) — the phatic function could be seen as a combination of the expressive and the appellative one — the speaker expresses his wish for contact and appeals to the hearer to enter into such contact; the poetic function, where language is used for its own sake, without a clear communicative goal — for example a nonsense limerick like There was a young lady from Imber, / Who built her house out of timber. / Her name was Brigid, / and she started out rigid, / but all the hard work made her limber! (the only point of this limerick is to play with the word timber); the metalingual function, where language is used to describe itself (this is a special case of the referential function).

Again, most utterances serve more than one of these functions simultaneously, but in many cases one of them is dominant.

Question 2.3.8.

Do you agree that poetry is always language for its own sake? Find examples providing evidence for and against this idea!

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Written by Anatol Stefanowitsch