Section 7.3 Derivation vs. inflection

There is another distinction that we can draw between affixes. Consider, again, these words introduced at the beginning of Section 7.2:

Both (b) and (c) contain an affix that attaches to the base law, but the function of the two affixes is fundamentally different. The affix {‑less} creates a new word: lawless is obviously related to the word law in form and meaning, but it is not the same word. By attaching the affix {‑less} ‘not having’ to law, we add a new word to the vocabulary of English. Affixes that derive a new word are referred to as derivational affixes.

In contrast, the affix {‑s} ‘plural’ does not create a new word: laws is not just related to the word law in form and meaning, it is the same word. By attaching the affix {‑s} to a noun, we do not add a new word to the vocabulary of English — we simply create a different form of the same word (the plural). Affixes that create a different form of an existing word are referred to as inflectional affixes (a complete overview of the inflectional affixes of English can be found in Section 7.4).

There are several differences between derivational and inflectional morphemes, all tied to their different functions.

Subsection Differences between inflection and derivation

A first difference is that derivation is always optional — nothing about the grammar of English forces you to derive the word lawless in order to express the idea that a person or a place are not governed by or willing to adhere to laws. Instead of saying For a time, the west was a lawless place, you can say The west was not governed by laws. In contrast, inflection is obligatory in the relevant contexts: if you want to modify the noun law by a numeral, for example, in the sentence The west knew only two laws: kill or be killed, you must attach the plural suffix {‑s}.

A second difference is that derivation can (but does not have to) be accompanied by a change in word class. For example, law is a noun, lawless is an adjective. (But note do and undo for a case of derivation without a change in word class.) Inflection can never lead to such a change. For example, laws is a noun, just like law. This is because derivation creates a new word, while inflection creates a word form of the same word. Read the subsection below if you need to brush up your understanding of word classes.

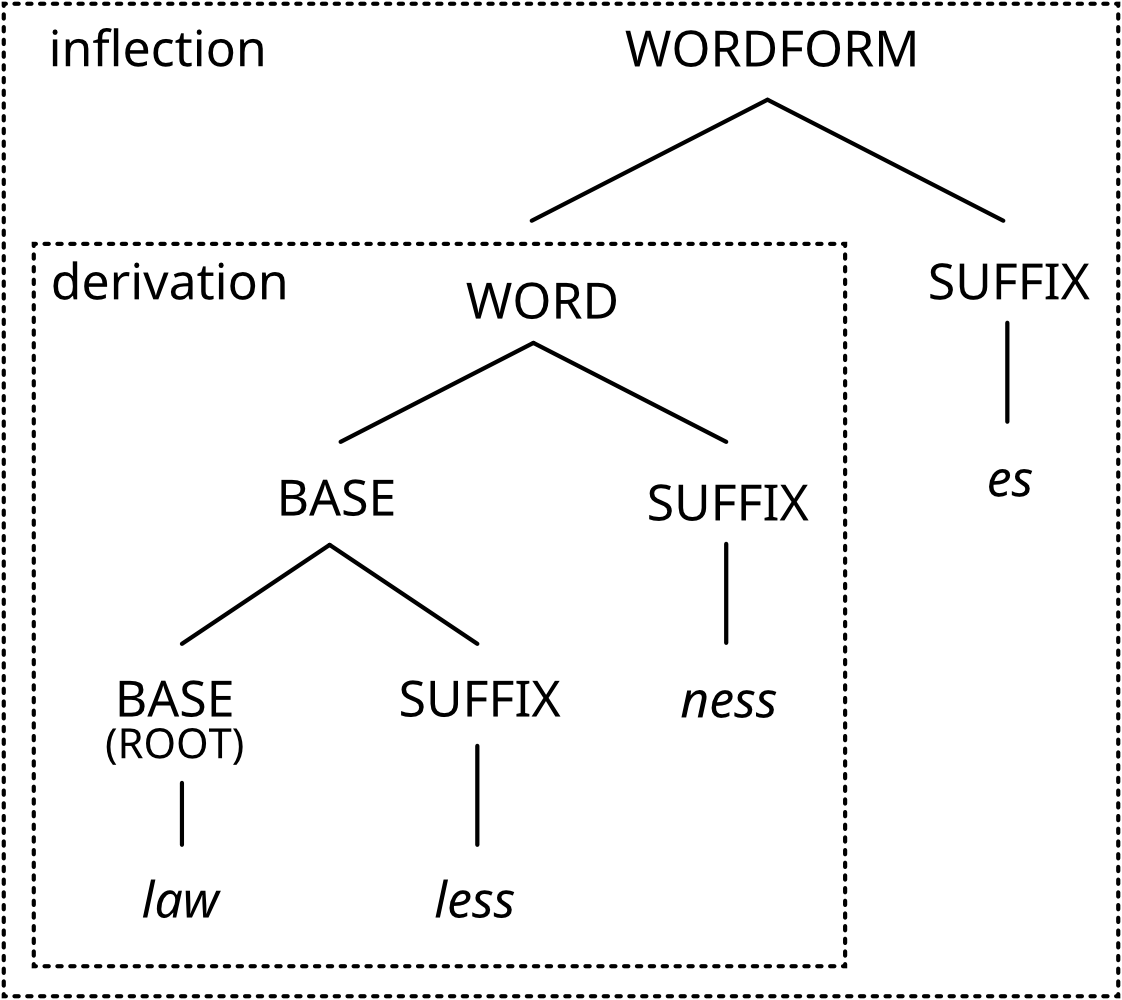

A third difference is that derivational affixes are almost always attached before inflectional affixes (see Figure 7.3.1) and derivational affixes cannot be attached to an inflected base. This is because they create new words from existing words, while inflectional affixes create different forms of these existing words. For example, we can form a plural of the derivative lawlessness (as in the Bible quotation and their sins and their lawlessnesses I will never remember any more, Hebrews 10:17), but we cannot derive an adjective from the inflected wordform laws using the affix ‑less: *lawsless.

A tree showing the word lawlessnesses, with a box labeled “derivation” around the part corresponding to “lawlessness” and a box labeled “inflection” around the entire word.

A final difference between inflectional and derivational morphemes is their productivity. While inflectional morphemes are generally highly productive, meaning that they can attach to (almost) every word of the appropriate word class, the productivity of derivational morphemes is normally limited in various ways — derivational affixes often cannot attach to all words with the appropriate word class, and even if they can, speakers often make no use of this potential. This is because inflectional affixes produce word forms with a very predictable meaning that are obligatory in certain contexts, so they must be able to create such forms for any word (of course, there are always a few exceptions, for example, nouns that cannot be pluralized). In contrast, derivational morphemes are used to create new words, and this only happens when those words make sense and when they are needed.

Subsection An excursion: word classes

In order to describe and distinguish derivational and inflectional processes, it is necessary to have a good grasp of word classes. This subsection provides a short overview.

You might be familiar with traditional semantic definitions for word classes — definitions that are based on a word’s meaning. If you ever learned that a noun is a “person, place or thing”, or that a verb is an “action word”, these are semantic tests. However, semantic tests don’t always identify the categories that are relevant for linguistic analysis. They can also be hard to apply in borderline cases, and sometimes yield inconsistent results; for example, surely action and event are “action” words, so according to the semantic definition we might think they’re verbs, but in fact these are both nouns! We therefore define word classes based on the grammatical contexts in which words or morphemes are used—their distribution.

In the following, we present some tests to identify the most important word classes in the context of morphology, which are nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs:

Nouns (N)

-

Syntactic tests for nouns:

-

Can follow a determiner

-

As in: an event or the proposal

-

-

Can be modified by adjectives

-

As in: a happy event or the new proposal

-

-

Can be the subject or object of a verb

-

As in: Events occurred. or We made proposals.

-

-

Can be replaced by a pronoun

-

As in: Events occurred. becoming They occurred.

-

-

Do not allow objects (without a preposition).

-

-

Morphological tests for nouns:

-

Have singular and plural forms: e.g. books, governments, happinesses

-

Note: The plurals of some abstract nouns can seem odd! Think outside the box to find contexts where they might naturally occur.

-

-

Verbs (V)

-

Syntactic tests:

-

Can combine with auxiliary verbs (e.g. can, will, have, be)

-

Can follow the infinitive marker to

-

Can take an object (without a preposition):

-

As in: kick the ball.

-

-

-

Morphological tests

-

Have a third person singular present tense form with ‑s

-

As in: (she/he/it) kicks, goes, proposes

-

-

Have a past tense form, usually (but not always) with ‑ed

-

As in: (she/he/it) kicked, went, proposed

-

-

Have a perfect / passive form, usually with ‑ed or ‑en

-

As in: (she/he/it) has kicked, gone, proposed

-

-

Have a progressive form with ‑ing

-

As in: kicking, going, proposing

-

Note: words in ‑ing are also often nouns!

-

-

-

Adjectives (Adj)

-

Syntactic tests:

-

Modify nouns (occur between a determiner and a noun)

-

As in: a happy event or the new proposal

-

-

Can be modified by very (but so can many adverbs!)

-

As in: very happy, very new

-

-

Do not normally allow noun phrase objects (if objects are possible, they must be introduced in a prepositional phrase)

-

-

Morphological tests:

-

Can often be suffixed by ‑ish

-

May have comparative and superlative forms (e.g. happier, happiest)

-

Adverbs (Adv)

-

Syntactic tests:

-

Modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs (anything but nouns!)

-

Cannot appear alone between a determiner and a noun

-

Can be modified by very (but so can adjectives!)

-

-

Morphological tests:

-

Many (not all) adverbs end in ‑ly

-

Subsection Critical cases

So, there are two types of morphological processes: derivational morphology, which is concerned with processes that lead to the creation of new words, and inflectional morphology, which is concerned with processes that lead to the creation of new word forms. The examples discussed above may have left you with the impression that the boundaries between these two types of process are always clear. The following two cases will show that this is not always the case.

The first example is the affix {‑ly}, as in lawless vs. lawlessly. It is treated as an inflectional affix by most researchers (and is presented as such in most textbooks), but if we apply the four criteria, we get mixed results.

First, we could argue that the affix is obligatory if we want to use an adjectival base to modify a verb: She acted lawlessly, not She acted lawless. Note that this is not true of all dialects of English, but it is true of those dialects that have the affix. This suggests that the affix is inflectional.

Second, we could argue that the affix derives an adverb from an adjective and must therefore be a derivational affix. Whether or not this is a good argument depends on whether or not we can argue convincingly that adverbs and adjectives are actually different word classes — the fact that they have distinct names may suggest this, but note that we consider participles to be verb forms, yet we still have a distinct name for them: “participle”, If you think about it, the only difference between adjectives and adverbs is that the former modify nouns and the latter modify verbs:

The meaning stays the same, so lawless and lawlessly really feel more like different forms of the same word. Thus, we could argue just as well that {‑ly} is an inflectional affix that must be attached to adjectives if they modify a verb instead of a noun.

Third, it it clear that {‑ly} does not attach to inflected stems, such as comparatives or superlatives: She grinned madly, *She grinned madderly, *She grinned maddestly. This, by itself, does not tell us anything: derivational affixes cannot occur after inflectional affixes, but in English, inflectional affixes cannot occur after other inflectional affixes either. The interesting question is whether inflectional affixes can attach to {‑ly}. If they can, this would be evidence that {‑ly} is a derivational affix. If they cannot, this could be evidence that it is an inflectional affix, or it could be evidence that the inflectional affixes in question cannot attach to adverbs at all.

So, which is it? The answer is that adverbs with {‑ly} can be inflected, as in the following examples (the first from Hamlin Garland’s novel The Eagle’s Heart, the second from Aldous Huxley’s “Eyeless in Gaza”):

- (3b)

- Helen was … feeling more and more sick with apprehension at every step. Walking slowlier and slowlier in the hope of never getting there.

However, speakers almost never do this in Present-Day English — you have to go to literary texts or older stages of English to find examples. This is not because adverbs cannot be inflected in general. There are a few adverbs that do not contain the affix {‑ly} — some are irregular, like well (corresponding to the adjective good), and some are not inflected, like fast (corresponding to the adjective fast). These adverbs are frequently inflected (He slept better, She walked faster and faster, …). This would be expected if {‑ly} were an inflectional affix.

Fourth, the affix has a very high productivity — it can attach to almost any adjectival base. There are a few exceptions, like the adjective good, which has the adverbial form well instead of goodly, but, as mentioned above, there are always a few exceptions. The high productivity suggests that {-ly} may be an inflectional affix after all.

The second example is the affix {‑ess}, which derives specifically female forms from male or gender-neutral human nouns, as in princess or waitress. It is generally considered to be a derivational affix, but, again, let us apply the four criteria.

First, it is hardly ever obligatory (in fact, it is hardly ever used at all, see below). We can refer to a female waiter as a waitress or a female actor as an actress, but we do not have to — we can use the gender neutral forms actor and waiter for people of all genders. This suggests that, indeed, it is a derivational affix.

Second, it is very difficult to say whether it creates a new word — is actress really a different word from actor, or is it just a different form? One could argue either way. The difference between the two words is highly predictable — a form with {‑ess} always means ‘a female version of whatever the stem refers to’, and the word with and without the suffix thus feel very much like different word forms of the same word. This suggests that it may be better thought of as an inflectional affix.

Third, the affix cannot attach to inflected bases, instead, inflectional affixes have to follow: Sigourney Weaver and Jodie Foster are among the world’s best actr-ess-es, not *…among the world’s best actor-s-ess. This suggests, again, that it is a derivational affix.

Fourth, the productivity is very difficult to assess. On the one hand, speakers simply do not use the affix anymore, and they never really did so in the history of English. It seems, then, that it has a low productivity, which suggests that it is a derivational affix. On the other hand, it can be attached to any human noun, and speakers occasionally do so — we do find isolated uses like professoress, programmeress and astronautess, for example. This suggests that the affix is highly productive, but that speakers simply choose not to use it productively — for example, because they feel that it is sexist to differentiate between men and women (Sigourney Weaver has commented publicly that she thinks of herself as an actor rather than an actress). This would suggest that it is an inflectional affix.

Does the difficulty in determining the status of the suffixes {‑ly} and {‑ess} suggest that our previously established criteria are useless? Not really. First, wherever there are categories, there can be phenomena that do not fit neatly into these categories. Second, such cases can help us in understanding the categories better — for example, note that the criterion of order — derivation before inflection — provided very clear results in both cases, while productivity turned out to be a problematic criterion. Thus, we might rethink using productivity as a diagnostic, or we might give the ordering criterion a more prominent place, but neither of these choices has an impact on the categories themselves.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Section “Free and bound morphemes” written by Anatol Stefanowitsch with minor inspirations from Catherine Anderson, Bronwyn Bjorkman, Derek Denis, Julianne Doner, Margaret Grant, Nathan Sanders, and Ai Taniguchi, Essentials of Linguistics. 2nd ed., Section “An excursion: word classes” adapted from Anderson et al. with edits by Arne Werfel; Section “Critical Cases” written by Anatol Stefanowitsch and Arne Werfel.