Use the rule in 6 to create different English NPs. Make sure you could represent them as a tree diagram.

Section 8.4 Phrase structure rules

Phrase structure is useful in the analysis of individual sentences, for example, in order to identify structural ambiguity, but it is also useful in the analysis of whole grammars. By analyzing a large number of phrases or sentences in terms of their phrase structure, we can identify the general syntactic rules that determine how phrases and sentences are constructed in a given language. Let us look at how this could be done.

Subsection The noun phrase

The example sentences in Section 8.3 contain noun phrases with different structures. Here are some examples:

Let us look at the phrase structure of each example in turn. Example (1a) and (1b) consist of a single noun and nothing else — a proper noun in the case of (1a) and a common noun in the case of (1b). The structure of these noun phrases is shown in (2):

This structure is not unique to examples (1a) and (1b) — the NP Aylin and the NP sushi, for example, have the same structure, and if we think of a combination of a first name plus a last name as a compound noun, so does the NP Al Gore. So, (2) is not just a description of specific noun phrases in specific sentences, but also a general rule for making a particular type of noun phrase in English! It tells you that you can take a noun and use it as a noun phrase.

The same is true of the phrase structure of the example in (1c) — it consists of an article and a noun, as shown in (3):

Other noun phrases with the same structure are a student, the cafeteria, the apartment, the package, the grass, the train, the tree, a garden hose (where garden hose is a compound noun), and the avocado. Again, (3) can be thought of as a description of these particular noun phrases, or as a general rule for making such noun phrases: we can make more English noun phrases by combining articles and nouns according to the phrase structure in (3).

The NP in (1d) consists of an adjective phrase (in this case, consisting of a single adjective) and a noun, its structure is shown in (4):

Other noun phrases with this structure are renewable energy, vegan pizza, and — with more complex adjective phrases — unbelievably green hair, and more convincing arguments. As before, we can make a large number of additional noun phrases by treating (4) as a rule for combining adjective phrases and nouns.

So far, we have three rules for creating NPs in English. Now look at the NP in (1e). It contains an article (like that in (1c)), and an adjective, like that in (1d):

Another NP that has this structure is a fascinating but very long documentary, and again, we can treat (5) as a rule for creating NPs by combining an article, an adjective phrase and a noun. We have four rules now, but note that the rule in 5 is just a combination of the rules in (2), (3) and (4): an English NP consists of a noun, optionally preceded by an adjective phrase, optionally preceded by an article. Using parentheses to show optionality, we can combine all our rules into one:

Question 8.4.1.

Next, look at the NP in (1f) — it does not have an article, instead, it has what is sometimes called a ‘possessive pronoun’, but what in linguistics is usually called a possessive determiner. Determiners are words that provide grammatical information about a noun, such as articles like a and the (which provide information about definiteness and, in some languages, number and gender), demonstratives (this, that, these, those, pointing out specific instances), quantifiers and numerals (some, many, one, seventeen, etc., providing information about quantity), and possessive determiners (my, your, etc.), providing information about possession. In order to include all of these, we can change the rule to the one shown in (7):

Next, look at the verb phrase in (1g). It consists of a determiner and a noun, followed by a PP, so we can simply add an optional PP to our rule:

This is not a complete rule for the English NP yet. It does not, for example, include the possibility of a relative clause, as in the student who has green hair. But it’s not too bad either — most NPs that you are likely to encounter in English texts are created using this rule. Except, that is, NPs that consist of just a pronoun. For these, we need an alternative rule:

The existence of this alternative rule explains why we can test whether a sequence of words is an NP by replacing it with a pronoun!

Finally, look at the NP in (1i). It contains the form Zoe’s, i.e, a combination of the NP Zoe and the possessive clitic we discussed in Section 7.5. In that section, we proposed a treatment of the possessive clitic as a word-formation rule, as shown in (10a), because we argued that it produces a unit that behaves like a word — a possessive determiner. However, it is a strange word-formation rule, because the clitic attaches to a phrase rather than a word or wordstem. So, alternatively, we could represent it as a phrase-structure rule, as shown in (10b):

- (10a)

-

Form: \(\text{[ X}{\tiny{\text{NP}}} ~ \text{=s]}{\tiny{\text{DET.POSS}}}\)Meaning: ‘belonging to X’

We could then argue that such a unit is a particular type of phrase — a “possessive phrase”, and that possessive determiners are actually a particular type of pronoun that can replace this phrase (at least that would explain the traditional label “possessive pronoun”)!

Question 8.4.2.

Since different languages have different grammars, phrase structure rules are specific to individual languages. Think about other languages you know — do they have the same NP rule as English, or a similar one, or a completely different one? If you know a language that has a different NP rule, try to formulate this rule!

Subsection The adjective phrase

We have seen two types of adjective phrases so far, shown in (11a) and (11b), but there are other types of APs, such as the ones shown in (11c) to (11f):

Obviously, adjective phrases always contain an adjective. In addition, they can optionally contain adverbs, as in (11b) and prepositional phrases, as in (11c), so the phrase structure rule for adjectives would look like this:

This rule also accounts for (11d), where more is a specific type of adverb (namely one that is used to form a comparative form with adjectives that do not have a morphological comparative). It also accounts for (11e), where than functions as a preposition.

Example (11f) is not covered by the rule: although enough seems to be used as an adverb here, it follows the adjective instead of preceding it. It is the only adverb in English that behaves like this, however, so we should treat it as an exception rather than postulating a rule that says that adverbs can follow adjectives in English!

Subsection The prepositional phrase

The example sentences in the preceding section also contained a number of prepositional phrases, for example those in (14):

They all have the following phrase structure:

This is the simplest rule we have seen so far — while NPs and APs can have many different forms, depending on which of the optional elements are used, PPs always seem to have the same form.

However, this is not quite true. First, prepositional phrases can contain adverbs:

- (15b)

- Zoe watched a documentary seemingly about renewable energy, but actually advertising cold fusion.

So we have to extend the rule as follows:

So what about the following examples:

The underlined words are called ‘spatial adverbs’ in traditional grammar. However, they do not really behave like typical adverbs — for example, they cannot modify an adjective or a preposition, as the phrase-structure rules for APs and PPs suggest, and they also cannot modify verbs, which is the typical function of an adverb. Instead, they behave like PPs — they occur in the same positions, as shown in (18):

In fact, the ’spatial adverbs’ are sometimes the same words as the prepositions, as in (17a) and (18a) or (17c) and (18c)! So, it makes sense to assume that these spatial adverbs are actually prepositions and that the NP in prepositional phrases is optional. Our rule for PPs would then look like this:

In fact, PPs can also consist of a preposition and another PP, as in The sun appeared from behind the clouds, so a more complete rule would look like this:

Subsection The verb phrase

Finally, the examples in the preceding sections also contained a range of different types of verb phrases, some of which are shown in (20):

We know that each of the underlined sequences is a single verb phrase — it can be replaced by do the same or do so as a whole, but not in parts:

- (21b)

- Zoe watched a documentary and Aylin did the same (but not: *… and Aylin did the same a telenovela).

- (21d)

- Zoe was talking about renewable energy and so was Aylin (but not: *…and so was Aylin about magical realism).

This is going to be important later on, but for now, look at the phrase structure of the individual examples:

All of them contain a verb, of course — that is why they are verb phrases. In the simplest case, this is all they contain, but in addition, they can optionally contain an NP, an AP or a PP. Using parentheses to indicate optionality, as we did before, and using a slash to indicate alternatives, we could combine these rules as follows:

However, things are a little more complex, as the following examples show:

These are the phrase structures corresponding to these examples:

In other words, VPs can contain (a) just a verb, (b) a verb and an NP, AP or PP, or (c) a verb and an NP plus an additional NP, AP or PP, so the phrase-structure rule has to look like this:

But things are even more complicated. Recall VPs like those in (27):

Again, we know that the underlined sequences are VPs, because they can be replaced by do the same, but in these cases, we can also replace parts of the VPs with do the same:

- (27a)

-

Zoe watched a documentary in the cafeteria……and Aylin did the same (i.e., she also watched a documentary in the cafeteria).…and Aylin did the same in the library (i.e., she also watched a documentary, but not in the cafeteria).

- (27b)

-

Aylin rolled the sushi with a rolling mat…… and Noah did the same (i.e., he also rolled sushi with a rolling mat).… and Noah did the same with a towel (i.e., he also rolled sushi, but not with a rolling mat).

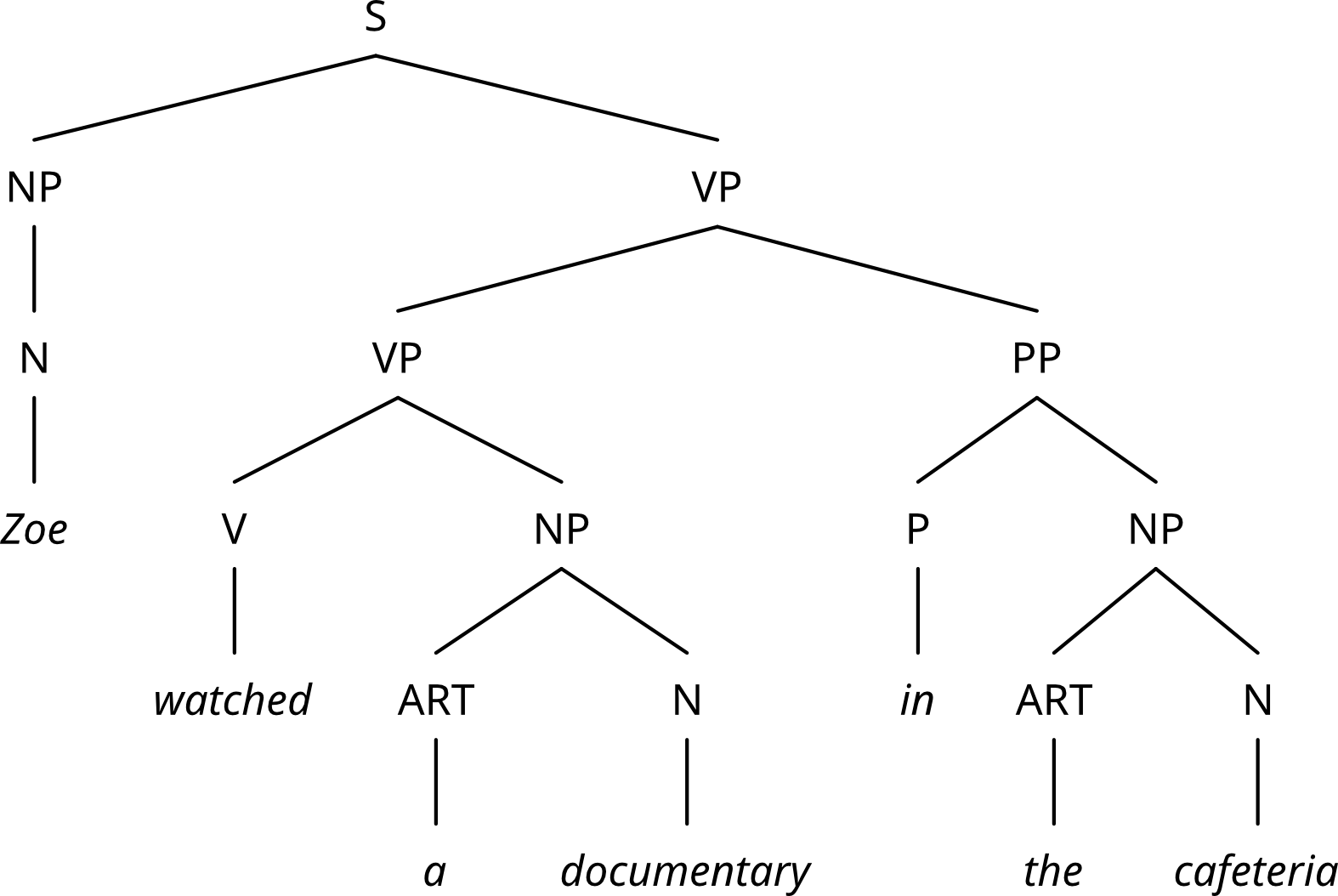

In other words, the smaller sequences watched a documentary and rolled the sushi are VPs, and so are the larger sequences. Remember that we represented this structure as shown in Figure 8.4.3

[S [NP [N Zoe]] [VP [VP [V watched] [NP [ART a] [N documentary]]] [PP [P in] [NP [ART the] [N cafeteria]]]]]

So, a VP can also consist of a VP and a PP (one or more PPs, in fact, but lets keep things simple):

This rule cannot be combined with the rule in (26) — we need both.

Subsection Auxiliaries and modals

You might wonder what to do about auxiliary verbs, like the one in (29a), or modal verbs, like the one in (29b):

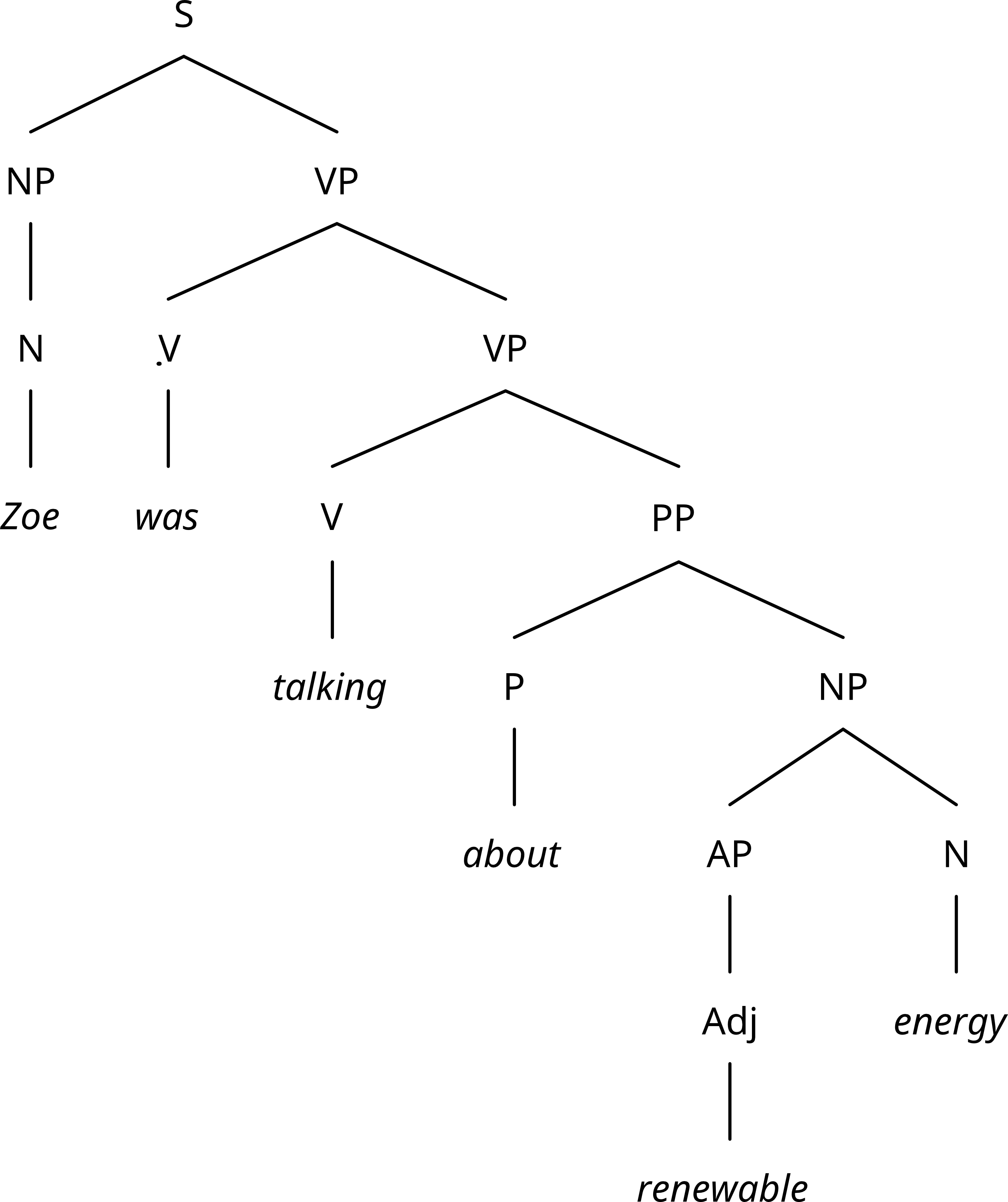

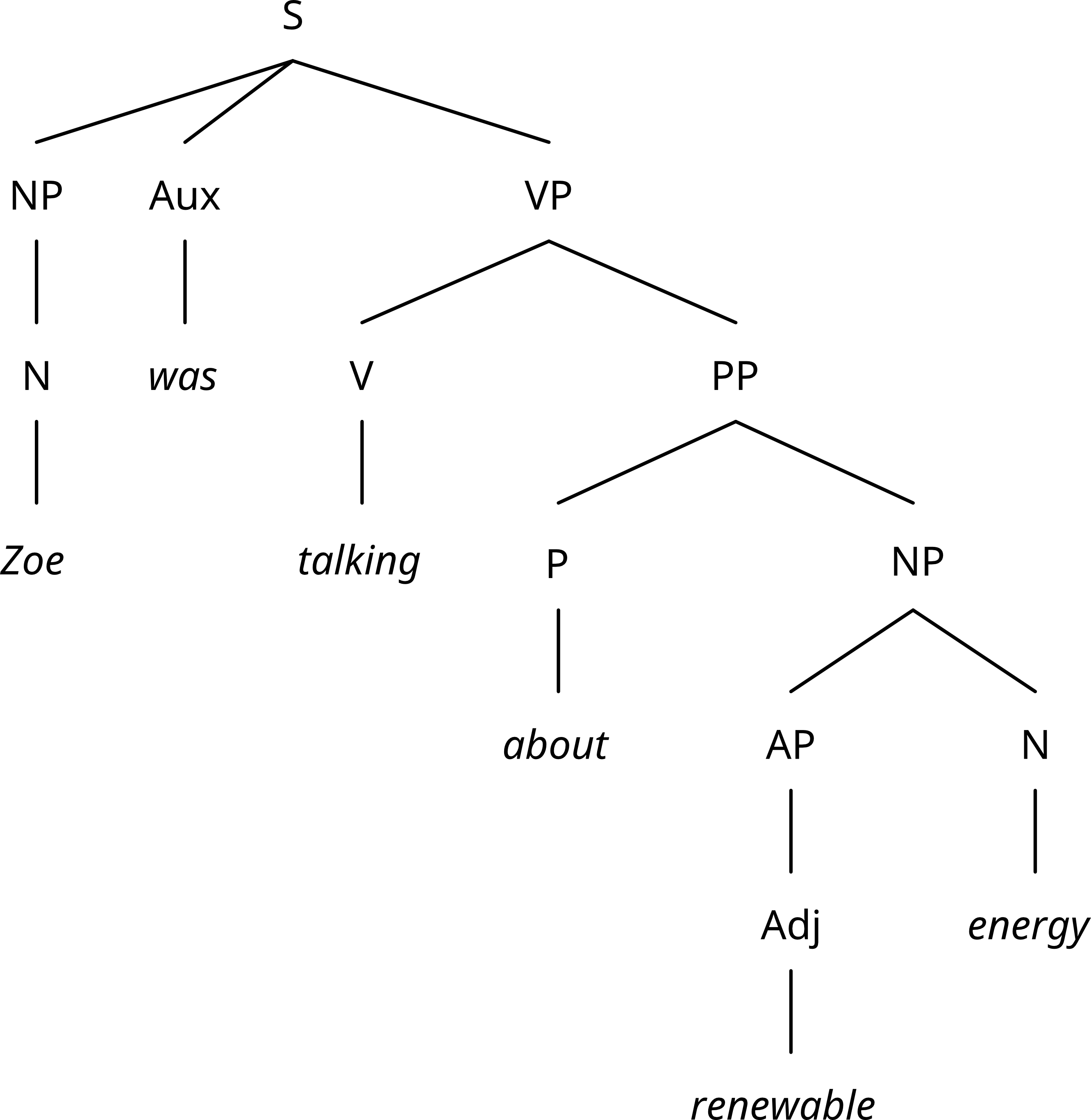

There seem to be two possibilities: either they are part of the verb phrase, as shown in Figure 8.4.4, or they form a constituent by themselves, as shown in Figure 8.4.5

[S [NP [N Zoe]] [Aux was] [VP [V talking] [PP [P about][NP[AP [Adj renewable]][N energy]]]]]

[S [NP [N Zoe]] [VP [V_aux_ was] [VP [V talking] [PP [P about] [NP [AP [Adj renewable]] [N energy]]]]]]

Unfortunately, constituent tests do not give us a clear answer as to which of the two analyses is correct. On the one hand, Fragment and movement tests suggest that auxiliaries (and modals) do not form a constituent with the verb phrase:

- (30a)

- What is she doing? — Watching the documentary.

- (30b)

- What is she doing? — * Is watching the documentary.

On the other hand, the deletion test shows that if we have a sequence of auxiliaries and modals followed by the verb, we can only delete sub-sequences that are contiguous to the verb, as in (31), but we cannot delete an auxiliary at the beginning or in the middle of a sequence, as in (32):

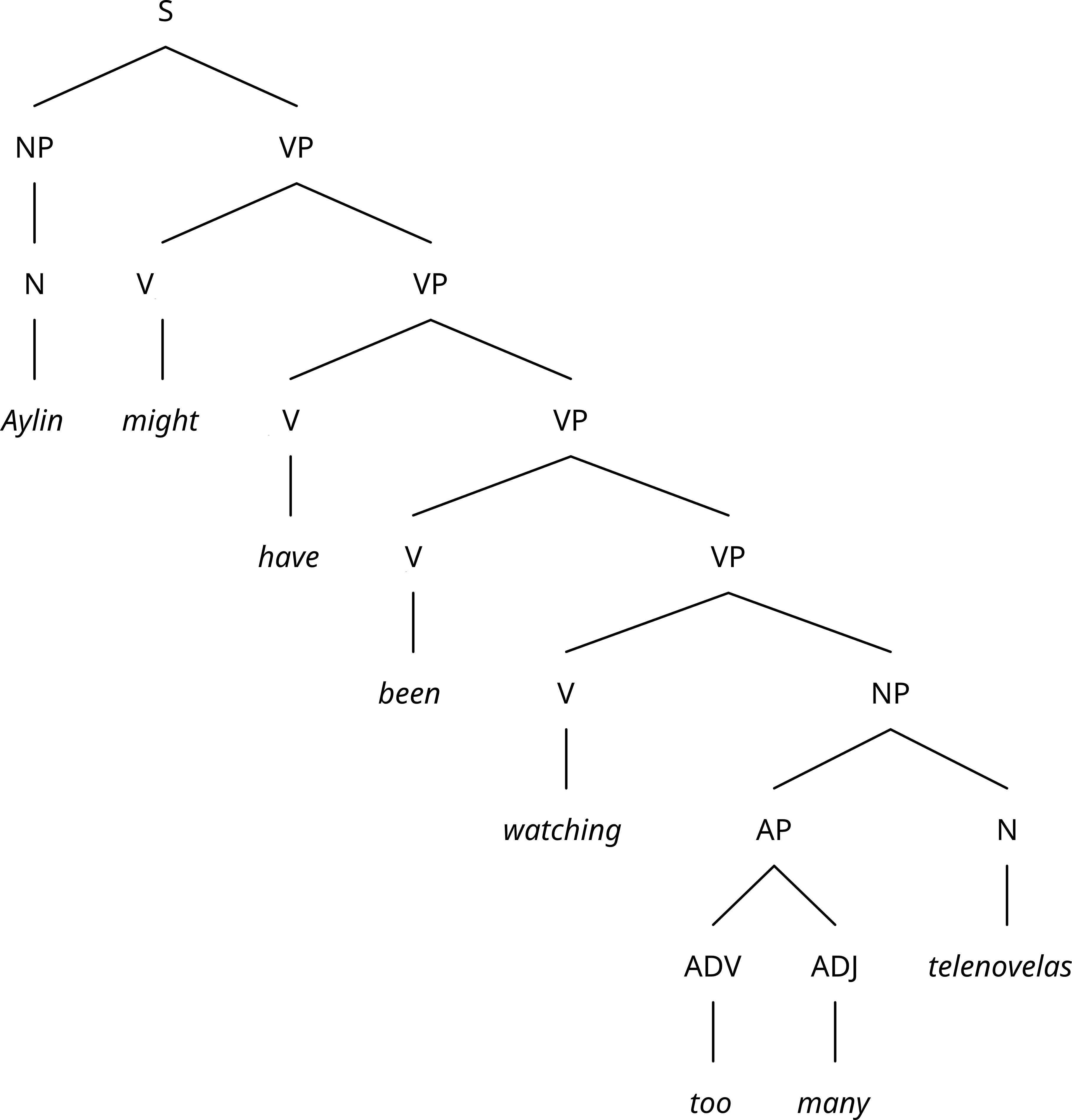

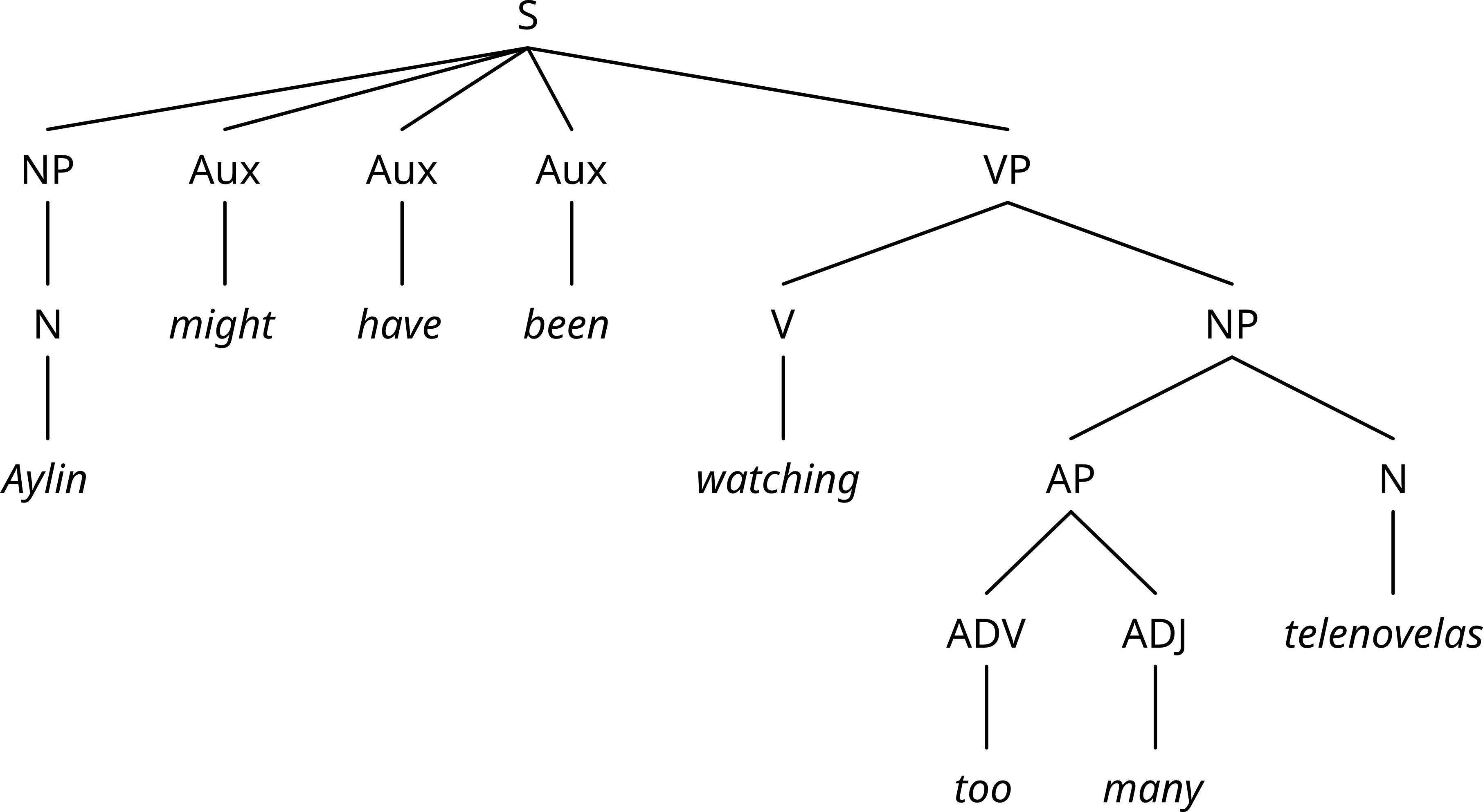

This is more easily explained if each auxiliary or modal forms a verb phrase containing the next one, as in Figure 8.4.6, than it is if the auxiliaries each have their own branch, as in Figure 8.4.7

[S [NP [N Aylin]] [VP [V_aux_ might] [VP [V_aux_ have] [VP [V_aux_ been] [VP [V watching] [NP [AP [ADV too] [ADJ many]] [N telenovelas]]]]]]]

[S[NP [N Aylin]][Aux might][Aux have][Aux been][VP[V watching][NP[AP [ADV too] [ADJ many]][N telenovelas]]]]

There are good reasons for preferring the analysis in terms of the hierarchical structure (for example, it is much easier to describe the order in which auxiliary verbs and modals occur in such sequences), and we are going to proceed as though this is the right analysis, so we need an additional phrase structure rule for VPs:

However, in terms of constituency structure, there are good arguments for both analyses.

Finally, note that auxiliaries can also be used as the main verb of a sentence — in this case, they follow the phrase structure rule in (26) above:

Subsection The adverb phrase

Adverbs are considered to be a major word class, and as such, we would expect them to head a type of phrase called adverb(ial) phrase. We have ignored this in the preceding sections and shown adjectives directly as modifiers in verb phrases and adjective phrases — not, because adverbial phrases do not exist but because they are a bit too complex to be discussed exhaustively in an introductory textbook. But we’ll give an overview of the basics to finish of this section. First, note that what is traditionally called “adverb” is a very heterogeneous category of words that do not behave in a consistent way. There are at least three subcategories. First, the spatial adverbs we discussed in the context of examples (17) and (18) above and which turned out to be prepositions. Second, so-called degree adverbs — words that indicate intensity, like very, quite, rather, extremely etc. And third, words related in meaning to adjectives from which they are usually derived by the suffix {-ly} (although there are irregular cases, like the adverb fast from the adjective fast or the adverb well from the adjective good).

Degree adverbs can modify adjectives, as in (36a), or adverbs related to adjectives, as in (36b), but they cannot modify verbs, as (36c) shows:

Adverbs related to adjectives, in contrast, can modify adjectives, as in (37a), other adverbs related to adjectives (although rarely), as in (37b), and verbs, as in (37c):

Thus, we need to posit at least two types of adverbial phrases — the one in (38a), where DEG stands for “degree adverb” and the one in (38b), where ADV stands for adverbs related to adjectives:

We need two types of phrases because they occur in different rules, and we must be able to distinguish them — (38a) and (38b) occur in APs and ADVPs, (38b) also occurs in VPs!

Question 8.4.8.

Look at all rules given previously in this section and think about whether ADV must be replaced by the rule in (38a), the one in (38b), or both.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Written by Anatol Stefanowitsch