Think of examples of other non-linguistic communication systems used by humans.

Section 1.1 What do we investigate when we investigate language?

We humans have a fascinating and (as far as we know) unique skill: we can synchronize our thoughts across space and time. For example, I am thinking about a tree at the moment of writing this in a café in Berlin in July 2025 — and now, so are you, in a different location and at a point in time that for me, right now, is in the future.

How is it possible for me to make you think of a tree? The answer would be less mysterious if you were sitting in the café with me, with me tugging at your sleeve and pointing at a tree across the street. Or if we were telepaths capable of sending and receiving thoughts to and from different points in each other’s past and future. However, neither of these things are the case.

The reason why we are both thinking about a tree — I at the time of writing and you at the time of reading — is, of course, that I used the word tree. In doing so, I made use of the fact that both you and I have, at some point in the past, learnt to associate a particular sequence of speech sounds (and later, a sequence of letters, i.e. shapes loosely related to these sounds) with a particular meaning. When I thought of a tree, I typed the sequence ⟨tree⟩, and when you saw the sequence ⟨tree⟩, it made you think of a tree. We have synchronized our thoughts (or, to use a more familiar term, we have communicated) using language.

Subsection Language and other ways of communicating

Linguistics is the scientific investigation of language in this sense of the word. Using language is not the only way in which humans communicate — other ways of doing so include using gestures like tugging at someone’s sleeve and pointing at something, using pictograms like one of those in Figure 1.1.1 (road signs indicating a ‘picnic area’) or giving someone flowers.

(a) A blue rectangle in portrait orientation with a white square containing the black silhouette of a bench to the left of a stylized coniferous tree leaning to the left; (b) a brown rectangle in portrait orientation containing a white silhouette of a person sitting on a bench at a table to the left of a silhouette of a straight coniferous tree; (c) a blue square containing a white silhouette of a bench to the right of a stylized deciduous tree leaning to the right; (d) a brown rectangle-like shape with jagged edges in landscape orientation containing the white silhouette of a bench and a table to the right of a stylized silhouette of a baobab tree.

We do not usually call such behaviours “language” (although some people may metaphorically refer to the act of giving flowers or other gifts as their “love language”), and they are not a primary object of investigation in linguistics. However, since they can be used to communicate, they may be of interest to linguists when they are used in combination with language. There is one class of human behaviours referred to as “language” that are not of interest to linguists at all — programming languages, such as Python, C++ or COBOL. Their function is too different from that of language as we understand the term here to be studied using the same tools (in fact, since they were intentionally created by humans based on well-understood mathematical and technical concepts, their properties are fully known, we do not need to investigate them scientifically at all).

Question 1.1.2.

There are also non-human ways of communicating — those used by animals. These are of interest to linguists only insofar as we can use them as a standard of comparison to work out the unique properties of human language (but of course, they are a fascinating area of investigation in their own right).

So, linguists investigate individual languages, such as English, French, Polish, Turkish, Arabic or Vietnamese as well as the abstract principles that underlie all human languages — the properties that make them human languages. We will discuss the most important of these properties in broad terms in the next section , and in more detail throughout this book, but very generally they include the following: languages have stable associations of sound and meaning (“words” like tree) and rules by which these can be combined into larger units (for example apple tree, the tree outside our apartment or Let’s climb that tree!).

Because individual languages are just different manifestations of the same underlying human skill, they are translatable into each other. So, if you are unsure whether a particular human (or other animal) behavior is a “language” or not, try translating it to English and try to take an English sentence and translate it into that behaviour. This will work flawlessly for French, Polish, Turkish, Arabic, Vietnamese, etc. (although it may require some thought), but not for gestures, traffic signs, flower bouquets or animal behaviours. For the latter, you may be able to paraphrase their general meaning in English, but trying the same thing in the opposite direction will not work.

Subsection Language and modality

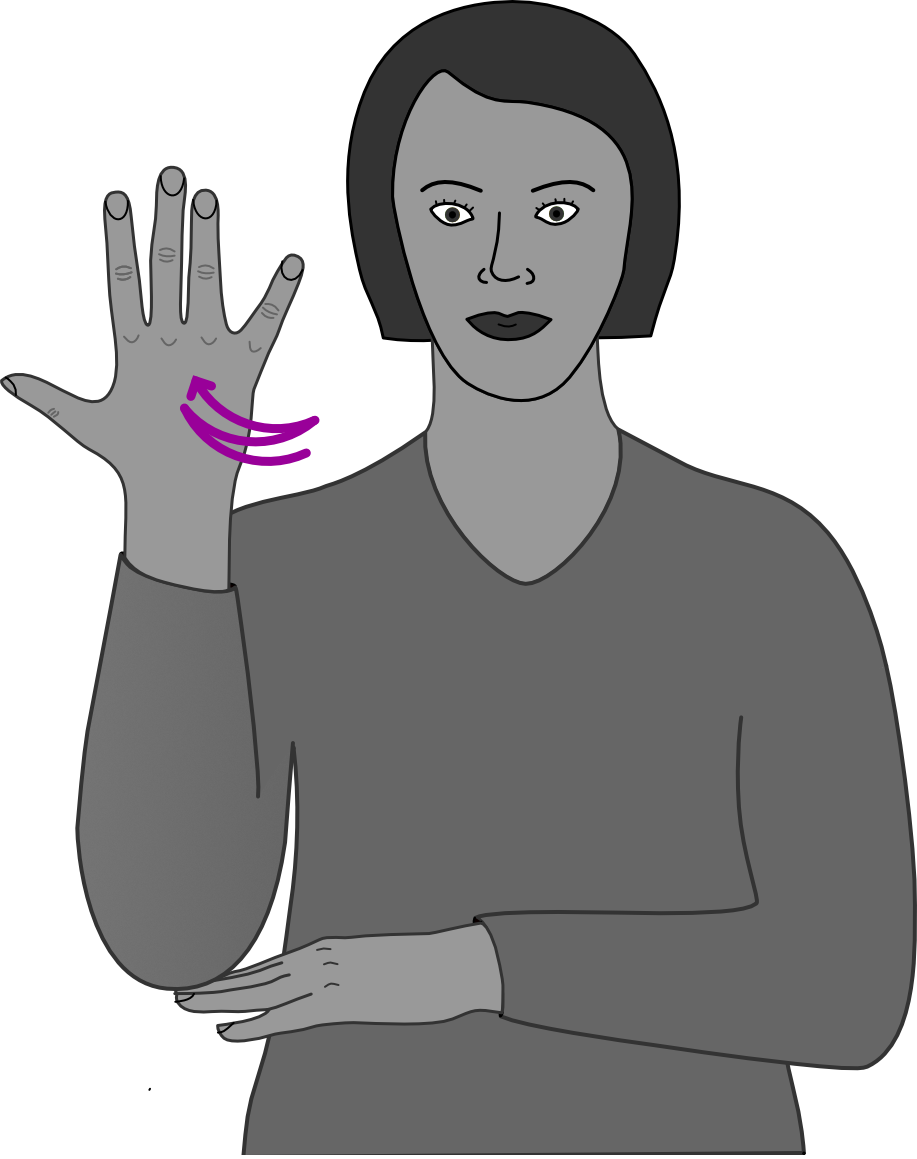

Earlier, we mentioned gesture as a human behaviour that is different from language, but that is an oversimplification. It is true for gestures like tugging at someone’s sleeve or pointing — gestures that are likely to accompany the use of language. However, there are also gestures that are language. For example, Figure 1.1.3 shows the word for ‘tree’ in American Sign Language. It consists of starting with the “gesture” depicted, and then twisting the right upper arm a quarter turn clockwise, a quarter turn anti-clockwise and a quarter turn clockwise again. This is a word, not a gesture imitating the shape of a tree (although you may note a relationship of similarity) — to distinguish such words from the types of gestures mentioned before, they are referred to as signs and languages consisting of such signs are referred to as sign languages (or signed languages). Except for their mode of expression (gesture instead of sound), sign languages are just like other languages, with words that are combined into larger units according to language-specific rules.

A b/w drawing of a person holding their left lower arm horizontally across their body with the hand stretched and palm-down, the right elbow resting on the back of the left hand with the right lower arm pointing vertically up and the right hand stretched, the fingers slightly apart. A pink arrow near the wrist of the right arm indicates a quarter turn clockwise, a quarter turn anti-clockwise and a quarter turn clockwise again.

The existence of sign languages illustrates another important property of human language: it is independent of a particular modality. The same general principles underlie spoken and signed languages, and anything expressed in English (or another spoken language) can also be expressed in American Sign Language (or another signed language) and vice versa.

Modality independence is also the reason why the same language may be expressed in different media. All spoken languages can be represented in the visual mode we call “writing” — the practice of using particular shapes to represent speech sounds (depending on the writing system these are called graphemes or syllabograms) and/or word meanings (these are called logograms). Not all spoken languages (and no signed languages) are regularly or systematically expressed in this way, but many spoken languages are. These tend to have a conventional way of doing so — something called an orthography that makes use of a particular writing system. For example, English is traditionally written using a variant of the Latin alphabet, with an orthography that, for historical reasons, does not have a very close relationship to the sound of words.

Subsection Language and writing

The use of a particular writing system and orthography often has cultural relevance for the members of a language community. From a linguistic perspective, however, speech (for spoken languages) and signing (for signed languages) are the main focus of interest, while orthography and writing systems are of relatively little importance. The reason for this is that speech and signing are primary modes of expression, while writing is a secondary mode:

-

in the history of humankind, speech and signing arose much earlier than writing ; as a consequence

-

all languages have a spoken or signed form, but not all languages have a written form; and

-

the written form of a language is an attempt to represent the spoken/signed form, not the other way around;

-

developmentally, language users acquire spoken/signed language before they learn to write; in fact

-

all humans learn to speak/sign at least one language unless they are severely cognitively impaired, but not all humans learn to write all (or any) of their languages;

-

all humans acquire spoken/signed languages naturally and without explicit instruction and they are able to do so as soon as they are born (in fact, there is evidence that hearing fetuses start learning to recognize the sounds of the languages spoken around them while still in the womb), while most humans need explicit instruction to learn to write;

-

the way words are pronounced (in speech) or articulated (in signing) changes slowly over time according to general tendencies of language change, while the spelling of words (or even the writing system used for an entire language) can change rapidly based on intentional decisions by the language users;

-

when the spoken/signed form of a language changes substantially, it is no longer the same language (think about Italian, French, Catalan, Spanish, Portuguese and other Romance languages, which all evolved from Latin), while a language remains the same if the orthography is reformed (as was the case, for example, in Germany in 1996) or a different writing system is adopted (for example, when Romanian speakers in Moldova switched from the Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet after the demise of the Soviet Union);

-

more generally, different languages can use the same writing system — English, Hausa and Vietnamese all use variants of the Latin alphabet —, and the same language can use different writing systems — for example, Serbo-Croatian in Serbia, Bosnia and Montenegro is written using both Latin and Cyrillic, and Levantine Arabic is written using the Arabic, the Latin or the Hebrew alphabet.

This does not mean that linguists ignore written language — they do investigate it (sometimes consciously, sometimes subconsciously). In large, literate language communities, written language plays an important role — in fact, there are media and social domains where it is the main medium of communication—, and understanding how it is used in that role is an important part of understanding how language works. However, it means that linguists always keep in mind (or at least try to keep in mind) that it is a secondary mode that is ultimately based on spoken/signed language. There are other secondary modes, by the way — some languages can be represented by whistling or drumming in a particular way. There are even tertiary modes of language, that represent writing in a different medium — for example, Morse code, which represents graphemes as sequences of short and long sounds, or semaphore, which represents graphemes as configurations of flags showing different colored patterns.

Subsection The study of language in other disciplines

Due to its central role in human societies, at least some aspects of language are relevant to all disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, but there are some where is a major focus of interest. These include, among others, psycholinguistics (a subfield of psychology concerned with language acquisition, production and comprehension), neurolinguistics (a subfield of neurology concerned with the way language is represented in the brain), language pedagogy (an interdisciplinary area of research concerned with issues of foreign-language teaching and learning), sociolinguistics (an interdisciplinary area of research concerned with the relationship between language and social factors such as class, gender, subculture, migration, etc.), and literary studies (concerned with a specific type of culturally relevant linguistic products — literary texts). Linguistics shares research interests and methods with all of these disciplines. What makes it special is that its focus in on the properties of language itself, the principles that make them languages in the first place. This textbook introduces these principles, mostly using the example of English, but occasionally bringing other languages into the discussion.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Written by Anatol Stefanowitsch