Section 6.5 World knowledge and word meaning

There is one important aspect of sense (or intension) that we have to address. As discussed above, we have used the word “concept” to refer to the sense of a linguistic sign. This is not wrong — clearly signs exist in the minds of humans, so both their form and their meaning must be mental concepts. However, word senses are not the only concepts humans have — any declarative knowledge that we have comes in the form of concepts. This poses a challenge for linguists: how do we distinguish the knowledge that we have about a particular entity (or property, state, process, etc.), sometimes called world knowledge or encyclopedic knowledge, from the meaning of a word referring to that entity (word meaning)?

There may not always be a clear boundary between these kinds of knowledge, but it is clear that they are not the same. If they were, there could be no referential synonyms — two words that refer to the same entity (property, process, …) but have different meanings, like the words morning star and evening star mentioned in Section 2.2. Both of them refer to the planet Venus, so if world knowledge and word meaning were the same, they should have the same intension — whatever we know about the planet Venus, which includes properties like ‘is a planet’, ‘is in orbit around the sun’, ‘is the second closest planet to the sun’, ‘is the first celestial object other than the moon to be visible in the evening sky’, ‘is the last celestial object other than the moon to be visible in the morning sky’. However, while this world knowledge may always be in the background when we use the words morning star, evening star or Venus, each of the three has a slightly different meaning, the first two focusing on the morning and evening sky, the last one being purely referential.

Consider the following properties of trees, which we have compiled from dictionaries and encyclopedias:

-

is a plant

-

can become taller than any other plant

-

is made of wood

-

has a single stem

-

has branches in the upper part of the stem

-

has roots

-

can live for many years

-

is used to produce lumber

-

reduces the erosion of soil

-

removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

-

produces its stem by secondary growth

-

can belong to many different species

-

some kinds have fruit that we can eat

-

some kinds are put into people’s houses and decorated for Christmas

-

most kinds are angiosperms, some are gymnosperms

Which of these are part of the meaning of tree and which of them are part of our knowledge about trees? For some properties, this may be easy to see: many of you probably did not know the information listed in 11 or 15. These are things that biologists know about trees, but other people generally do not; since all speakers of English know how to use the word tree, these properties can therefore not be part of its meaning. This may seem obvious, but it is important to remember: language users sometimes appeal to expert definitions when arguing about the meaning of a word, but they are wrong to do so — experts often take words from everyday language and give them a more precise meaning in their field, but that does not change the meaning of the word in general language. (Therefore, if you want to find out about word meaning, you should consult a dictionary rather than an encyclopedia.)

But what about other pieces of knowledge that all language users are likely to have about trees, such as the fact that they have branches in the upper part of their trunk or that they can live for many years? It has been suggested that only those properties should be considered part of the word meaning that are necessary and sufficient to distinguish categories of entities from each other (remember the idea of a taxonomy of features discussed in the preceding section). For the word tree, these properties would be:

-

is a plant (distinguishes trees from people, animals, rocks, manufactured objects, etc,)

-

is made of wood (distinguishes trees from all other plants except shrubs)

-

has a single central stem (distinguishes trees from shrubs)

These properties are necessary in that any entity that we can truthfully call tree must have them and sufficient in that no additional properties are needed to distinguish trees from other entities. The question is: do these three conditions collectively represent the sense of the word tree? It seems that the notion of leaves and branches figures very prominently in the meaning of the word tree — should we exclude them just because we don’t need them to distinguish trees from other plants? The Greek philosopher Plato is said to have defined the word man (in the sense of ‘human being’) as a ‘featherless biped’, and it is true that the features ‘has two legs’ distinguish humans from all other entities except birds, and ‘featherless’ distinguishes them from birds, so collectively, these two properties are necessary and sufficient to distinguish humans from all other entities. But nobody would claim that ‘featherless biped’ is actually the meaning of human being.

This problem can be alleviated somewhat by choosing necessary and sufficient properties more carefully — the linguist Robbins Burling calls humans the talking ape in the title of a famous book. He did not intend this to be a definition, but note that, ‘can talk’ and ‘is a primate’ are also individually necessary and collectively sufficient properties distinguishing humans from other entities. They also feel much more central to the meaning of human than the features ‘does not have feathers’ and ‘has two legs’. So, how do we recognize that both Plato’s and Burling’s definition consist of necessary and sufficient conditions and how do we know that one of them captures more relevant aspects of meaning than the other? This can only be because the intension of human is not limited to some smallest possible set of necessary and sufficient conditions.

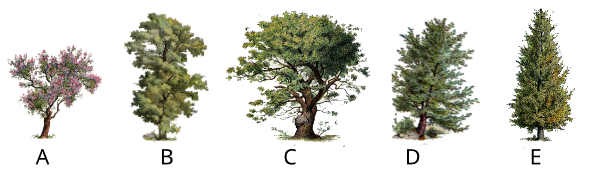

Another approach to distinguishing word meaning from world knowledge is by thinking about the shared nature of language: we use words to communicate, and for this to be possible, their meaning must be shared. But what if your tree has properties different from those of mine? When you hear the word tree without context, which of the trees in Figure 6.5.1 matches your mental image most closely?

Five trees in a row: A) a tree with pink blossoms, B) a decidous tree with branches along the entire trunk, C) a decidous tree with branches growing only in the upper part, D) a coniferous tree with a roundish shape, E) a coniferous tree with a triangular shape

For us, it is the tree in C. This tree is one of the two trees shown that actually fully matches what we have so far assumed to be the definition of a tree: the trees in B, D and E have branches beginning in the lower part of their stem, not, as most dictionaries state, in the upper part of the tree. And the trees in D and E do have leaves if we adopt a biologist’s definition of leaf, but not if we adopt the dictionary definition given above, which corresponds to our everyday understanding of the word. In everyday language, we would call the leaves of the trees in D and E needles. What the dictionaries have given us is not in fact a list of features shared by all trees, but a list of features that we typically associate with trees. We can include another feature, that the dictionaries do not mention: we do not typically think of trees as having colorful petals — this is why we think of the tree in C rather than the one in A.

The following definition probably captures our shared associations with the word tree:

-

is a plant

-

can become very tall

-

is woody

-

has a single stem

-

has branches in the upper part of the stem

-

has green, flat leaves

Only the first and the third property are necessary for the inclusion of a referent in the extension of tree, and they are not sufficient to distinguish the meaning from that of the word shrub. How can this be? The best explanation is that the world within which we define the meaning of words is a bit simpler and has less variation than the actual world. The definition given above describes the properties that make up the intension of the word tree based on an idealized concept of what trees are like — this is sometimes called a prototype concept, the meaning would be the prototypical meaning. In the real world, matters are more complex, so we have to allow for a certain degree of mismatch when applying our idealized meanings to real-world referents.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Written by Anatol Stefanowitsch