Think about what features you would have to posit to distinguish bears from other animals, birches from other trees, brambles from other shrubs, boats from other artefacts, boulders from other natural objects and beauty from other abstract entities. How many of the features you have to posit seem plausible candidates for semantic atoms?

Section 6.4 How to represent meaning

Before we look at meaning in more detail, let us think about how to represent it. We have said or implied throughout the preceding chapters and the preceding sections of this chapter that meaning takes the form of “concepts”, which we did not define any further, but which we assumed to be mental states. To be a little more precise, we could say that the meaning of a linguistic sign is a mental state that is related to the mental state we would have if we directly experienced the referent (or relation between referents) associated with the sign. It is more abstract than the mental state associated with a particular referent — it is what all mental states associated with all potential referents have in common.

But how do we represent mental states? As humans, we have evolved exactly one tool to do so: language. So, whatever the meaning of a word actually is, the only way we can represent it is using other words. This brings with it a number of problems, most importantly, the problems of increasing abstractness and of circularity.

The most straightforward way of representing the meaning of a word using other words is the type of definition found in dictionaries — as we have done repeatedly throughout this book. A typical definition of the word tree (compiled from a number of well-known dictionaries) would be the following:

tree, n /tɹi/ a long-lived plant with a single thick wooden stem that grows to a great height, with branches growing from its upper part, and leaves

Such definitions are attempts to summarize in simple terms the knowledge that language users have about the referents of the word. As such, they rely on the knowledge that language users have about the referents of the words used in the definition — the definition of tree relies heavily on the words plant, stem, branch, and leaf, among others. Of course, in order for the definition to capture what we know about the potential referents of the word tree, these words would also have to be defined. Typical definitions would be the following:

plant, n /plænt/ a living thing that grows in the earth, on surfaces or other plants, or in water, usually has roots, a stem and leaves, and produces seedsstem, n /stɛm/ a central, tube-shaped part of a plant that grows above the ground and to which branches or leaves are attachedbranch, n /bɹænt͡ʃ/ a part of a tree that grows from its stem and has leaves attached to itleaf, n /lif/ a flat part of a plant that is attached to a stem or branch

You can see the problem of circularity: the definition of tree uses the word branch, and the word branch uses the word tree. Likewise, the definition of the word stem uses the word leaf and the definition of leaf uses the word stem. In each case, you already have to know the meaning of one of the words to understand the definition of the other.

You can also see the problem of abstractness: The word tree is defined using the word plant, the word plant is defined using the word thing. How is thing defined? A typical definition is the following, which uses the word object:

thing, n. /θɪŋ/ an object that the language user cannot or does not want to name

A typical definition of object is the following:

object, n. /ˈɑb.d͡ʒɛkt/ something with a stable form that can be perceived by sight and touch and that is not alive

The word thing is obviously not used in the dictionary definitions in the way that it is defined — first, it is not used because the lexicographer does not want to name it, as it is already named at the beginning of the definitions, second, it does not mean ‘object’, as objects are defined as ‘not alive’, so a ‘living thing’ would be a contradiction.

Instead, thing is used in the way that we have used the word entity at various points in the book — a typical dictionary definition for entity is the following:

entity, n. /ˈɛn.tɪ.ti/ something that exists separately of and can be distinguished from other parts of the world

(In fact, it is not entirely typical — most dictionaries use the word thing to define entity, which leads us back to the problem just mentioned.)

The problem with this definition is that it is so abstract that it can only be understood in terms of concrete examples: we have to know a range of entities — people, ideas, objects, plants, animals, etc. — in order for this definition to make any sense at all.

The same problems exist if, instead of using dictionary definitions, we define words in terms of lists of properties, as we have also done above, for example, when stating the meaning of tree as ‘is a plant’, ‘is perennial’, ‘is made of wood’, ‘has a single trunk’, ‘has branches’, ‘has leaves’. Such a list format forces us to think more precisely about the properties that define the extension of a word, and so it can be more useful than a dictionary definition written as a continuous text, but the two are essentially just different representations of the same information — we can easily paraphrase a dictionary definition as a list of properties or vice versa.

There are two ways of dealing with this problem. The first one would be to simply accept it. When we are describing the meaning of a word, we are using language to describe commonalities of the mental experiences that humans have when interacting — or thinking about interacting — with one or more of its referents and the relations between referents. It would be surprising if language would allow us to do so in a way that is free of circularities and free of complex relationships between more abstract and more concrete meanings. Since as linguists we are describing the meaning of linguistic expressions for humans, not for aliens or robots, we can rely on the assumption that those humans will somehow make sense of these descriptions. The circularity and the abstractions are often unproblematic when discussing the meaning of a morpheme or the difference in meaning between two or more morphemes.

The second way of dealing with this problem would be to come up with a restricted set of expressions that cannot and do not need to be further defined but that can be used to define all other linguistic signs — atoms of meaning, so to speak. This has been attempted repeatedly, usually not very systematically.

One such attempt that you will occasionally see is to postulate semantic features (or semantic components) and define the meaning of words in terms of the presence or absence of these features. Such features should (a) be able to distinguish the meaning of the word in question from other words and (b) be useful for defining many different words. Such features would be organized hierarchically yielding a taxonomy of all words of a language.

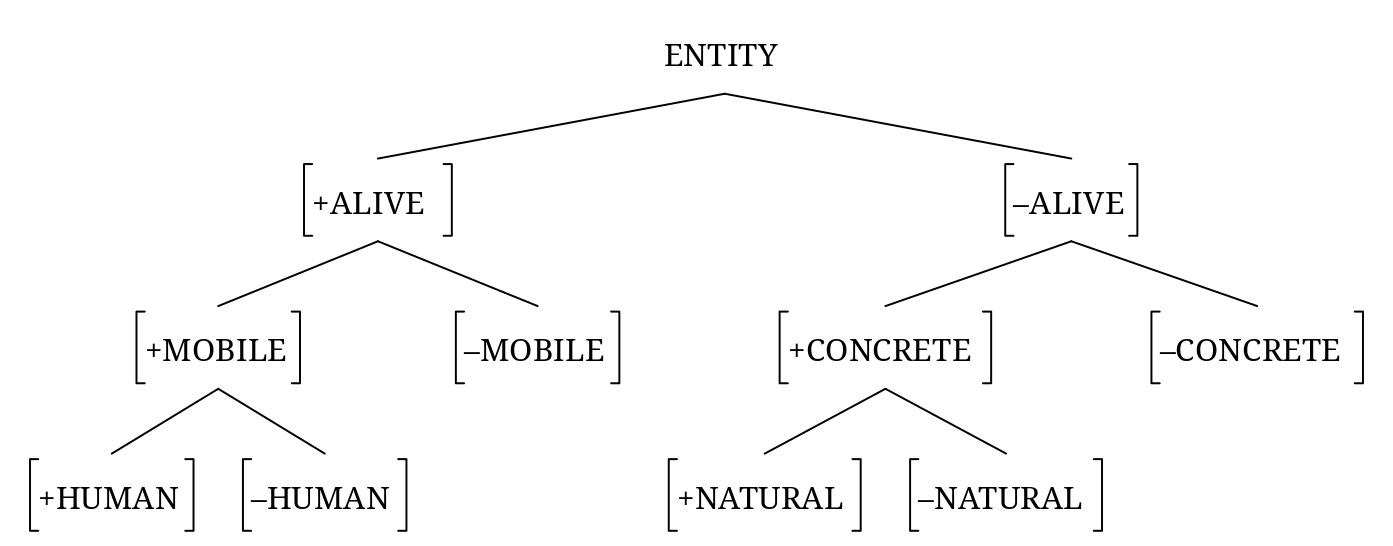

You will not be surprised that nobody has ever managed to create such a feature hierarchy for a substantial portion of the vocabulary of a language. To illustrate the complexity of the task, consider the hierarchy we would need to define a small portion of words from the letter B of a dictionary: bear, beauty, birch, boat, boulder, boy, bramble. All of them are entities in the sense of the term discussed above. A major distinction, and one that is likely to be useful for many other words, is that between entities that are (potentially) ALIVE (bear, birch, boy, bramble) and those that are not (beauty, boat, boulder). Within the first category, there is another major distinction between plants and animals (including humans). We might distinguish them by the feature MOBILE. Within the category of ALIVE/MOBILE entities, we have to distinguish between HUMAN and non-human animals (although humans are animals from a scientific point of view, we do not feel as though they are and we do not treat them linguistically as though they are). Within the domain of entities that are not potentially alive, we might want to distinguish between those that are CONCRETE (can be seen and touched, like boulder and boat) and those that are not (like beauty), and within the the former, we might want to distinguish between NATURAL and non-natural entities. This gives us the taxonomy of features shown in Figure 6.4.1

A taxonymy

This taxonomy allows us to distinguish the meaning of the very general expressions human, animal, plant, natural object, artificial object (artefact), and abstract entity. Not all of these would be used in everyday language, some are still too general.

The word boy would have the features [+ALIVE, +MOBILE, +HUMAN], but it would share these features with all other words for human beings. To distinguish it from girl, we would have to add the feature [+MALE] or [–FEMALE], depending on which of these we consider basic. To distinguish it from man, we would have to add the feature [–ADULT]. Thus, boy would be defined as [+ALIVE, +MOBILE, +HUMAN, –FEMALE, –ADULT]

The words birch and bramble would have to be distinguished from each other (one is a tree, one is a shrub), and from other plants. The features we would need to do so no longer have the generality of the features we have posited so far — they both have trunks, as opposed to other plants, but [± TRUNK] does not seem very plausible as a semantic atom, and we would not need it to distinguish any words other than tree and shrub (and their synonyms). The fact that trees have a single trunk and shrubs do not poses another problem: we cannot easily specify it in terms of presence or absence. It would be better to have some form of quantification — [0 TRUNK] (for other plants), [1 TRUNK] (for tree), [\<1 TRUNK] (for shrub).

Question 6.4.2.

Problems like this led most linguists to abandon the idea that the meaning of words can be described in terms of semantically simple and general features. However, many linguists believe that there are some features of this kind that are useful when modeling meaning, because they pick out aspects of a word’s intension that are relevant to morphological and syntactic rules. We will discuss this idea briefly in Chapter 7.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Written by Anatol Stefanowitsch