Describe the words bat, pig and cod in this way.

Section 3.6 The International Phonetic Alphabet

Subsection Segmentation

We have been talking about phones as if it were obvious what they are, but this is not always the case. It is sometimes easy to find a clear separation between the phones in a given word, that is, to segment the word into its component phones, but sometimes, it can be very difficult.

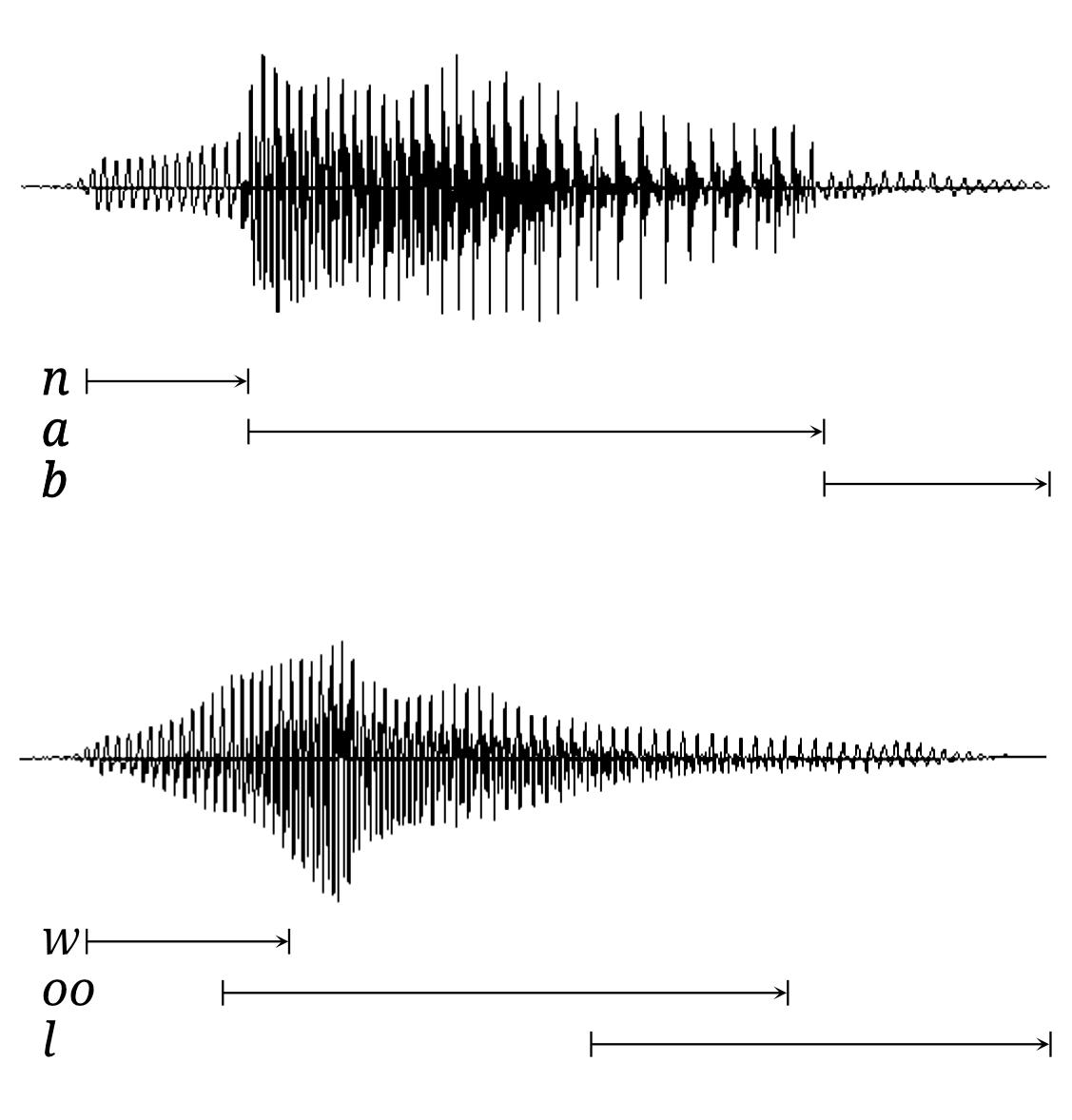

Let us take a small detour into the field of acoustic phonetics and look at the waveforms of two words, nab and wool. Waveforms are visual representations of an acoustic signal in terms of their overall amplitude (i.e., the air pressure produced by the signal) at different points in time (the ones shown here were produced using the free audio editing software Audacity, using sound recordings of an American English speaker provided as part of the Wiktionary entries for the two words).

Both words consist of three phones — a consonant phone, followed by a vowel phone, followed by another consonant phone. But how do we know this? Certainly not from the spelling, since spelling is an extremely poor reflection of the phonetic form of a word at best, and often not a reflection at all. Perhaps there is something about the acoustic signal itself that tells us where to segment a word into phones? The answer is that sometimes there is, sometimes there isn’t: the waveforms for the two words, presented in Figure 3.6.1, show a notable difference in how easy it is to segment nab and wool.

Two waveforms. Top waveform for the word nab is segmented into three distinct regions, labelled n, a, and b. The right waveform for the word wool has overlaps in the regions corresponding to w, oo, and l and the boundaries of these regions cannot easily be determined by looking at the waveform.

The waveform for nab contains abrupt transitions between three very different regions, and these correspond very well to the points at which you would hear the beginning and end of the individual phones. In comparison, the waveform for wool has smooth transitions from beginning to end, with no obvious divisions between phones. The points at which you would hear the approximate beginnings and ends of the three phones overlap and they do not correspond very closely to visible properties of the waveform.

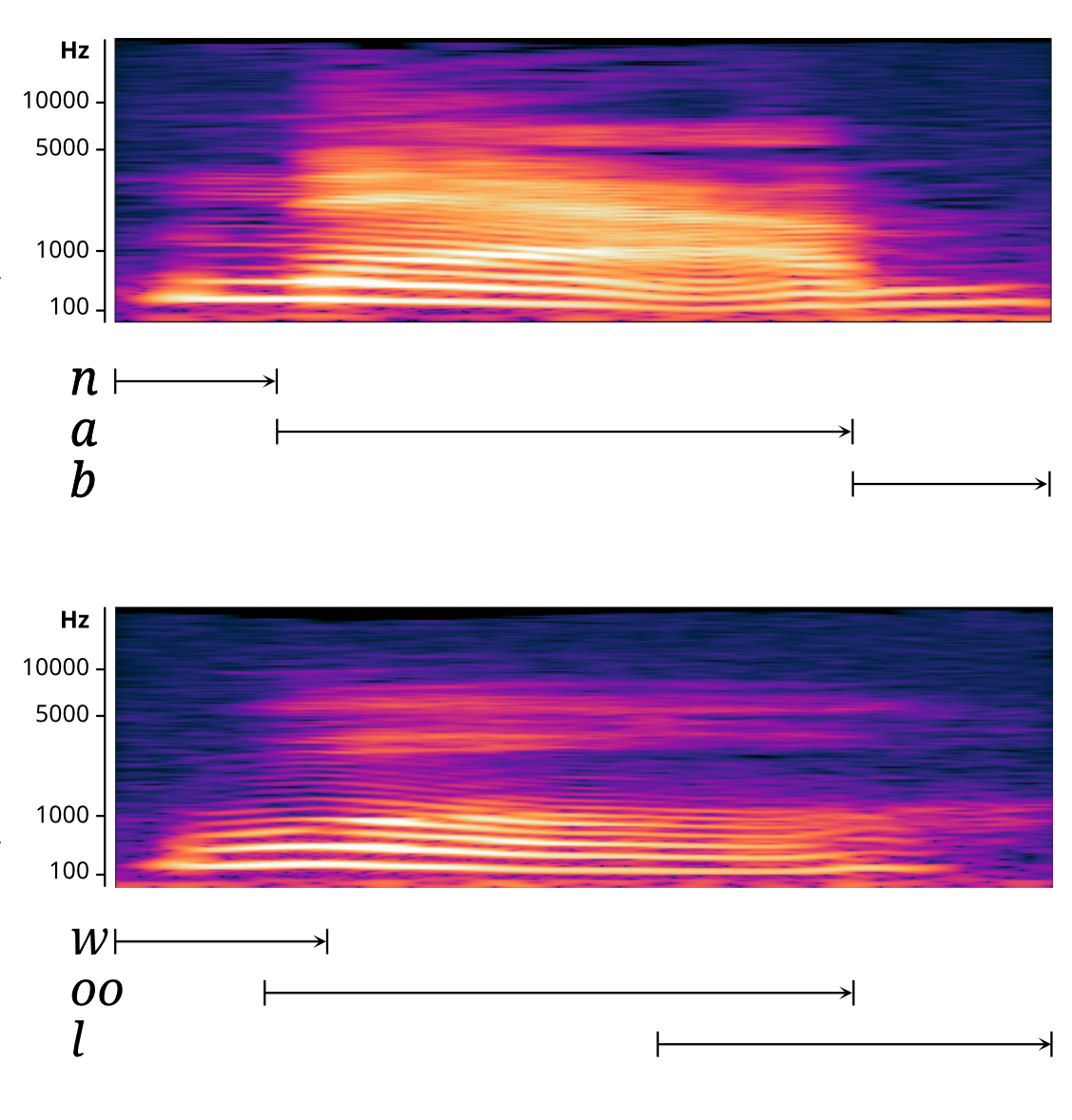

We can get more specific information about speech signals by looking at spectrograms, which are diagrams that represent the acoustic signal in terms of their amplitude at specific frequencies. The two spectrograms in Figure 3.6.2 represent the same two words as the waveforms in Figure 3.6.1

Two spectrograms. Top spectrogram for the word nab is segmented into three distinct regions, labelled n, a, and b. The bottom waveform for the word wool has overlaps in the regions corresponding to w, oo, and l and the boundaries of these regions cannot easily be determined by looking at the waveform.

Again, we can see the transitions between the phones very well for the word nab, while it is more difficult for wool, where we can see roughly where the vowel phone begins and ends, but where the beginnings and ends of two consonant phones cannot be easily determined. It should be clear that spectrograms are a very useful tool in phonetic analysis, but ultimately, a phonetician must train and rely on their hearing skills to analyze the phones of a spoken language. For the purposes of this textbook, the words will be presented already segmented into individual phones, but it is important to remember that the segmentation of raw data from a spoken language is a complex skill that takes a lot of practice. (There may even be disagreements about the right segmentation of a word.)

Subsection Transcription

When we have identified the individual phones in a word, we want to write them down — transcribe them — in a way that conveys the relevant information about them to another linguist in a consistent and unambiguous way.

We can produce precise, consistent and unambiguous descriptions using the categories introduced in the preceding sections — we could say that the phonetic structure of nab is “a voiced alveolar nasal consonant, followed by an open front unrounded vowel, followed by a voiced bilabial plosive” and that the phonetic structure of wool is “a voiced labial-velar approximant, followed by a close back rounded vowel, followed by a voiced alveolar lateral approximant”.

Question 3.6.3.

Such descriptions are accurate, but very cumbersome — imagine a whole sentence or even a longer spoken text being described in this way.

A usable transcription system should provide symbols for these combinations of articulation features. You might think that that is what the orthographies of spoken languages do, but this is not the case.

As mentioned earlier, the orthographies of most languages do not represent phones in a consistent or unambiguous way. In the preceding sections, we did use orthographically represented words to describe sounds — for example, we talked about “the vowel in the word beat”. But this only works if you already know how the word spelled beat is pronounced — with a close front unrounded vowel. The orthography itself does not tell you this: the letter sequence ea can also stand for an open-mid front unrounded vowel (as in head), an open back unrounded vowel (as in heart), a vowel that starts out as a close-mid front unrounded vowel and then becoms a slightly centralized close front unrounded vowel (as in great), an open-mid central unrounded vowel (as in the British English pronunciation of search), a rhoticized open-mid central unrounded vowel (as in the American English pronunciation of search), and others. And each of these vowels can also be represented by other letters or letter combinations: the one in head by ai (in said) or e (in bed), the one in heart by a (in smart) or ua (in guard), the one in great by ai (in bait) or a (in hate), to give you just a few examples.

Note also that even if you do know how a particular orthographically represented word is pronounced, this does not always allow you to deduce which sound someone has in mind when they write something like “the vowel in beat”. If we were to say, for example, “the vowel in either”, “the vowel in data” or “the vowel in route” — you would have to know how they pronounce these words, as these words have different pronunciations for different speakers — the vowel in either could be the same as that in heat or as that in height, the vowel in data could be the same as that in bait or as that in bat, and the one in route could be the same as that in bout or as that in boot.

Granted, English orthography is particularly bad at representing phones, but all writing systems have inconsistencies and irregularities of this type. In addition, not all languages contain all possible phones, and so even the most consistent and regular writing systems will not be able to represent the phones that do not occur in the language they were developed for. This is the second reason why we cannot use existing writing systems to represent the phonetic structure of words — we need a writing system that works for any language.

Several such writing systems have been devised, all based on the idea that each combination of articulatory features should be represented by one — and only one — letter symbol and that every letter symbol should represent one — and only one — combination of features. The system most widely used today is the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Subsection The International Phonetic Alphabet

The International Phonetic Alphabet (abbreviated IPA) was created by the International Phonetic Association, founded by British and French linguists in the late 19th century and still in existence today. The first version was proposed in 1897 and has undergone many revisions as our understanding of the world’s spoken languages has evolved.

The IPA uses mostly letter symbols from various versions of the Latin and Greek alphabets and a number of newly invented symbols (or variations of symbols). For example, the symbol [n] stands for a voiced alveolar nasal and [b] stands for a voiced bilabial plosive, which is what these letters represent in most orthographies based on the Latin alphabet. The symbol [æ] stands for a low front unrounded vowel, which is what it normally represents in the versions of the Latin alphabet used for Danish, Norwegian and Icelandic, and [w] stands for a voiced labial-velar approximant, which is what it usually represents in English. The symbol [ð] represents a voiced dental fricative, which is what it normally represents in Icelandic (and in Old English), [ɫ] represents the “dark” L-sound found in word-final position in many varieties of English, [ʊ] represents a slightly centralized close rounded back vowel, and [ə] represents a central mid unrounded unstressed vowel. These last three letters are variations of letters from the Latin alphabet.

Using these symbols, the phonetic structure of the phrase <nab the wool> can be transcribed as [næbðəwʊɫ]. This is much simpler than listing the features of each phone in order to describe it! IPA characters are enclosed in square brackets [ ] to clarify that they represent phonetic structure. Note that orthographic forms are enclosed in angled brackets < > in the context of phonetic analysis, to clarify that they do not represent phonetic structure.

The full IPA chart can be downloaded from the website of the International Phonetics Association here. There are also some online versions that are accessible for screenreaders, such as this one created by Weston Ruter. Note that the IPA includes not just letter symbols, but also a number of diacritics, smaller glyphs like [ ̪ ] and [ʰ] that are placed above, below, through, or next to the basic letters of the IPA to indicate small variations in the way the corresponding phones may be pronounced in a given language. The squiggly line through the [ɫ] in <wool> above is such a diacritic, indicating that the body of the tongue is raised towards the velum. Using these diacritics, phoneticians can create more or less detailed phonetic transcriptions — broad transcriptions that give a general idea of the phones occurring in a word or phrase, and narrow transcriptions that give a very precise idea.

Subsection Transcribing English with the IPA

We will discuss the symbols most useful to the transcription of English varieties in the remainder of this section, and we will mostly stick to broad transcriptions. Learning the IPA takes a lot of time, practice, and guidance, and it is not just about memorizing symbols. The underlying structure and principles behind the organization of this alphabet are what really matter. In this way, the IPA is like the periodic table of elements in chemistry. So, while it is helpful to know that Na is the chemical symbol for the element sodium with atomic number 11 and that [m] is the IPA symbol for a voiced bilabial nasal, it is much more important to know what these concepts are and what those terms mean. What is sodium? What does it mean for an element to have an atomic number of 11? What does it mean for a phone to be voiced? How is the vocal tract configured for a bilabial nasal? In reading the remainder of this chapter, you should be able to build a solid foundation in understanding how phones are articulated, so that you can start using the IPA notation in a meaningful way.

Subsection Consonants

We begin with consonants, which are generally easier to identify accurately and which do not vary very much across varieties of English (at least not as long as we stick to a broad transcription).

Table 3.6.4 lists the plosives and affricates typical of the major dialects of English with their IPA symbols and example words containing each consonant in various positions, where possible. For each word, the portion of the spelling that corresponds to the phone is in bold. Finally, a phonetic description of each consonant is also given.

| example | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| symbol | initial | medial | final | description |

| [p] | pan | rapid | lap | voiceless bilabial plosive |

| [b] | ban | rabid | lab | voiced bilabial plosive |

| [t] | tan | atop | let | voiceless alveolar plosive |

| [d] | den | adopt | led | voiced alveolar plosive |

| [t͡ʃ] | chin | batches | rich | voiceless postalveolar affricate |

| [d͡ʒ] | gin | badges | ridge | voiced postalveolar affricate |

| [k] | can | bicker | lack | voiceless velar plosive |

| [ɡ] | gain | bigger | lag | voiced velar plosive |

| [ʔ] | — | uh–oh | — | voiceless glottal plosive |

Depending on the specific dialect of English you are transcribing, you may need additional symbols. For example, in some varieties of Indian English, the voiced and voiceless alveolar plosives are retroflex (with the tip of the tongue curled back, as shown in Section 3.2). The IPA symbols for retroflex plosives are [ɖ] (voiced) and [ʈ] (voiceless).

As discussed in Section 3.3, the alveolar consonants are normally apicoalveolar (which is what the symbols in Table 3.6.4 reflect), but some speakers may pronounce them with the blade of the tongue. If that detail is necessary, these consonants can be transcribed as [t̻] and [d̻], using the diacritic [ ̻ ] for ’laminal’. Regardless of the active articulator, some speakers may pronounce these consonants on the back of the teeth rather than on the alveolar ridge, in which case, they would be transcribed as [t̪] and [d̪], using the diacritic [ ̪ ] for ’dental’.

The glottal plosive (also frequently called a glottal stop) is only a marginal consonant in English. It can be found as the catch in the throat in the middle of the interjection uh-oh. Some speakers also have it elsewhere, such as in the middle of some British English pronunciations of the word bottle. It is articulated by making a full stop closure with the vocal folds, blocking all airflow through the glottis.

Table 3.6.5 lists some fricatives of English.

| example | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| symbol | initial | medial | final | description |

| [f] | fan | wafer | leaf | voiceless labiodental fricative |

| [v] | van | waver | leave | voiced labiodental fricative |

| [θ] | thin | ether | truth | voiceless interdental fricative |

| [ð] | than | either | smooth | voiced interdental fricative |

| [s] | sin | muscle | bus | voiceless alveolar fricative |

| [z] | zone | muzzle | buzz | voiced alveolar fricative |

| [ʃ] | shin | Haitian | rush | voiceless postalveolar fricative |

| [ʒ] | genre | Asian | rouge | voiced postalveolar fricative |

| [h] | hen | ahead | — | voiceless glottal fricative |

The most notable variation here is that some speakers do not have [θ] and [ð], and instead use [t] and [d] or [f] and [v], depending on the dialect and the position in the word. Postalveolar fricatives are usually somewhat rounded, so they could be more narrowly transcribed as [ʃʷ] and [ʒʷ]. The voiced postalveolar fricative [ʒ] is one of the rarest consonants in English, occurring in just a handful of words (for example, <pleasure>, <measure>, <garage> and <genre>), and many speakers pronounce it as an affricate in word-initial and word-final position. For example, you may hear speakers pronounce the initial consonant of <genre> and the final consonant of <garage> as the affricate [d͡ʒ] rather than the fricative [ʒ].

Table 3.6.6 lists some sonorants of English. Across the world’s spoken languages, sonorants tend to be voiced by default, because their high degree of airflow causes the vocal folds to spontaneously vibrate, unless extra effort is put in to keep them from vibrating. This is true for English, so the phonation of the sonorants is not listed here.

| example | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| symbol | initial | medial | final | description |

| [m] | man | simmer | ram | bilabial nasal |

| [n] | nun | sinner | ran | alveolar nasal |

| [ŋ] | — | singer | rang | velar nasal |

| [l] | lane | folly | ball | alveolar lateral approximant |

| [ɹ] | run | sorry | bar | alveolar central approximant |

| [j] | yawn | onion | — | palatal central approximant |

| [w] | won | awake | — | labial-velar central approximant |

A few of these sonorants warrant extra discussion. The alveolar nasal [n] has much of the same variation as the alveolar plosives, with some speakers having a laminoalveolar articulation [n̻] and some having a dental articulation [n̪]. The velar nasal [ŋ] is often one of the most surprising phones of English to English speakers who are new to phonetics, because is not easily identifiable as its own phone. Many people are misled by the spelling and think they say words like singer with a [ɡ], but in fact, most speakers have only a nasal there, so that singer differs from finger, with singer having only [ŋ] and finger having [ŋɡ]. There are speakers who do genuinely pronounce all words like these with a [ɡ] after the nasal, but even then, the nasal they have is still velar [ŋ], not alveolar [n].

A notable consonant here is [w], which is special among the consonants of English in being doubly articulated, which means that it has two equal places of articulation. It is both bilabial (with an approximant constriction between the two lips) and velar (with a second approximant constriction between the tongue back and the velum). Its place of articulation is usually called labial-velar. English used to consistently have two labial-velar approximants, a voiced [w] and a voiceless [ʍ]. Very few speakers today have both of these, but some pronounce the words witch and which differently, with voiced [w] in witch and voiceless [ʍ] in which.

Subsection Vowels

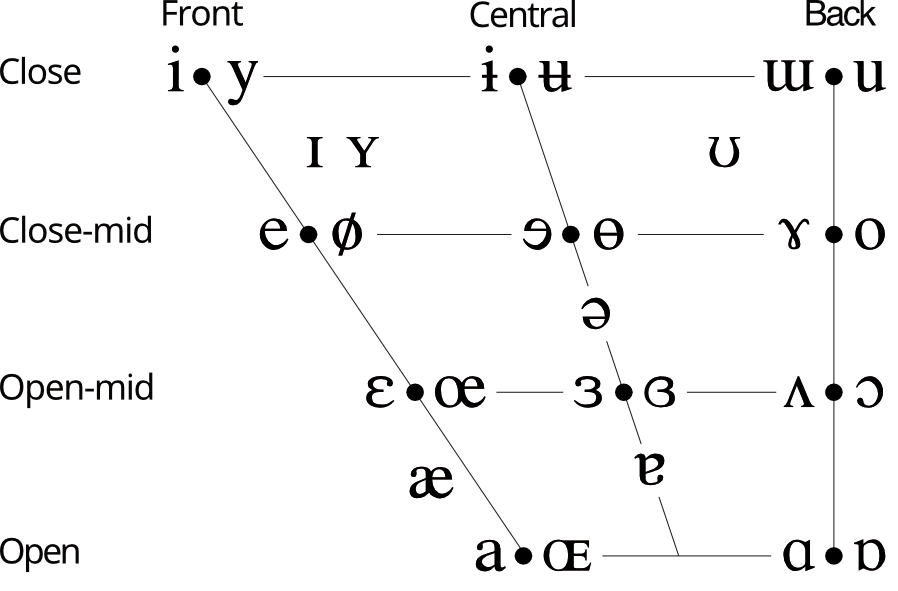

Now we can move on to the vowels. Figure 3.6.7 shows the vowel diagram we already saw in the previous section, but this time, the IPA vowel symbols for each combination of openness, backness and rounding are given (where there are two symbols, the one on the right always represents the rounded variant).

The IPA vowel chart: A trapezoid grid with the dimensions Front-Central-Back and Close-Close Mid-Open Mid-Open containing the basic vowel symbols of the IPA

Vowels are where much of the variation in pronunciation occurs across English dialects, and fully describing all of the vowels in English would take up an entire textbook of its own. Note that this is not a general property of spoken languages overall. Some are like English, with most dialectal variation in the vowels, but others have much more dialectal variation in the consonants, while others may have a relatively even mixture of variation in both consonants and vowels. We will focus on four standard varieties of English here: British English, US English (typically referred to as “American English” in English linguistics), Australian English and Canadian English.

In order to study the variation of vowels across varieties of English, the British phonetician John C. Wells devised a list of words that, collectively, are supposed to be able to demonstrate all possible distinctions for the major varieties. For some varieties, it has to be extended in minor ways, but it has remained very useful. Table 3.6.8shows this list along with the vowels in the four varieties (for the “rhotic” varieties, i.e. those where the consonant [ɹ] can occur after a vowel, this is shown in the table to remind you of this, but of course these cases are not vowels, but sequences of a vowel and an [ɹ]).

| Word | British (BrE) | Australian (AusE) | CanaDian (CanE) | US (AmE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fleece | iː | iː | iː or ɪi | i |

| happy | i | i | i | i |

| kit | ɪ | ɪ | ɪ | ɪ |

| near | ɪə | ɪə | iːɹ | ɪɹ |

| face | eɪ | æɪ | eɪ | eɪ |

| dress | ɛ | e | ɛ | ɛ |

| square | ɛə | eː | ɛɹ | ɛɹ |

| trap | æ | æ | æ | æ |

| price | aɪ | ɑe | ʌɪ | aɪ |

| pride | aɪ | ɑe | aɪ | aɪ |

| moucell> | aʊ | æɔ | ʌʊ | aʊ |

| cloud | aʊ | æɔ | au | aʊ |

| nurse | ɜː | ɜː | ɜɹ | ɝː |

| goat | əʊ | əʉ | oː or oʊ | oʊ |

| letter | ə | ə | əɹ | əɹ |

| comma | ə | ə | ə | ə |

| goose | uː | ʉː | uː or ʉu | u |

| foot | ʊ | ʊ | ʊ | ʊ |

| cure | ʊə/(ɔː) | ʊə | ʊɹ or ɜɹ | ʊɹ |

| strut | ʌ | ɐ | ʌ | ʌ |

| th>ought | ɔː | oː | ɒ or oː | ɔ or ɑ |

| saw | ɔː | oː | ɒː | ɑ |

| north | ɔː | oː | ɔɹ | ɔɹ |

| force | ɔː | oː | ɔɹ | ɔɹ or ɔʊɹ |

| choice | ɔɪ | oɪ | ɔi | ɔɪ |

| palm | ɑː | ɐː | ɒ | ɑ |

| start | ɑː | ɐː | ʌɹ | ɑɹ |

| star | ɑː | ɐː | ɑɹ | ɑɹ |

| bath | ɑː | ɐː | æ | æ |

| lot | ɒ | ɔ | ɒ | ɑ |

| cloth | ɒ | ɔ | ɒ | ɔ or ɑ |

This table is quite complex, but it is useful in two ways: first, it shows the substantial variation in vowel qualities across the four varieties — this variation would only increase if we added some other major varieties of English, such as Irish English, Indian English or South African English, let alone regional standards and local dialects within these varieties. So, be sure to remember that the vowel inventories in the table are an idealization that you can use to orient yourself in the much messier reality of studying the vowel inventories of actual speech communities or even individual speakers within the English-speaking world.

It also shows that the varieties differ in the number of vowel phones they have, although you have to study the table carefully to see this: in many cases, a number of words in the list have the same vowel in one variety but different vowels in another — this is an indication that one of them has fewer vowel phones overall. For example, note that in US and Canadian English, trap and bath both contain the vowel [æ], while in British and Australian English they have different vowel sounds: [æ] in bath and [ɑː] (BrE) or [ɐː] (AusE) in bath. This is not because US/Canadian English does not have a low back vowel [ɑ] — they do, CanE has [ɒ] and AmE has [ɑ], and they use them, for example, in palm, just like BrE and AusE. In other words, they have the same potential distinction in vowel quality, but they use it in slightly different places.

However, CanE and most varieties of AmE also use the same back vowel that they use in palm in lot, thought and saw (in CanE, the latter is longer than the former, but the quality is the same). Here, BrE and AusE also use different phonemes: British English has [ɒ] and [ɔː] in lot and thought/saw, and AusE has [ɔː] and [oː]. Thus, BrE and AusE have four different vowels in these five words, while CanE and AmE only have two. This is a quantitative difference: BrE and AusE really have more vowels than AmE (CanE makes up for the difference in a different place that we will return to immediately). In AmE, things are a little more complex: some varieties do have a difference between lot and thought, with [ɑ] in the former and [ɔ] in the latter, so they have one more vowel phone as compared to the major variety of AmE, but still one less than BrE or AusE. The varieties that do not distinguish between lot and thought used to do so in the past, but the two vowels have merged (this is called the lot-thought merger, or the cot-caught merger).

As just mentioned, Canadian English has fewer vowels than BrE and AusE in the set just mentioned, but makes up for this in a different set: the other three varieties all have the same diphthong in pride and price — BrE and AmE have [aɪ], AusE has [ɑe]. Canadian English, in contrast, has [aɪ] for pride, but [ʌɪ] for price. A similar difference exists for mouth and cloud — the other three varieties do not make a distinction here, using [aʊ] (BrE/AmE) or [æɔ] (AusE) for both. Canadian English, in contrast, has [aʊ] for cloud, but [ʌʊ] for mouth. This is referred to as “Canadian raising” (because, [ʌ] is higher in the vowel space than [a]), we will briefly come back to it in Section 4.3.

Let us now briefly point out some noticeable differences in vowel quality. First, while BrE and AmE do not have the monophthongs [e] and [o], using these phones only as part of the diphthongs [eɪ] and, in the case of AmE, [oʊ], AusE and most varieties of CanE have [o] and AusE also has [e]. Interestingly, however, they use them in completely different ways. Australian English uses [o] where the other varieties use [ɔ] (BrE and some varieties of AmE), [ɒ] (CanE) or [ɑ] (most varieties of AmE) and [e] where the other varieties use [ɛ], and it does not use [ɔ, ɒ, ɑ] and [ɛ] at all. In other words, it uses these monophthongs instead of other monophthongs.In contrast, most CanE speakers use the monophthong [oː] where the other varieties use the diphthongs [əʊ] (BrE) [əʉ] (AusE) or [oʊ] (AmE).

A second interesting difference concerns the rhoticity mentioned above. In Canadian and US English, the consonant [ɹ] can occur after vowels, in British and Australian English, it cannot. This has led to two differences in vowel quality. In the non-rhotic varieties (BrE and CanE), the vowels that preceded an [ɹ] sound in older stages of the language — which are generally still represented in the orthography by a sequence of the vowel and the grapheme r — developed into long vowels or diphthongs. In BrE, we find [ɑː] in star, [ɜː] in nurse, [ɔː| in north, [ɛə] in square, [ɪə] in near and [ʊə] in cure. In CanE and AmE, the corresponding vowels are all short monophthongs.

A final interesting difference also concerns rhoticity. In AmE, vowels preceding [ɹ] are often realized simultaneously with the [ɹ], leading to what is called a “rhoticized vowel”. In most cases, this simultaneous realization is optional, in slow, careful speech, the two phones are still recognizable as a sequence (although they tend to blend into each other). In one case, the rhoticization is an obligatory feature of the vowel: in the vowel in nurse. Rhoticization can be represented in the IPA by a small hook. This is a fixed part of the character for the nurse vowel: [ɝː], but it can also be added to other vowels in order to allow an accurate transcription.

A final remark pertaining to all varieties of English: The two mid central vowels [ʌ] and [ə] are often treated as related pronunciations of the same vowel, based on whether or not they occur in a stressed syllable (see Section 3.7 and Section 4.6 for more about syllables and stress). For now, just note that some vowels of English are pronounced louder and longer than others, which we call stressed, while the other softer and shorter vowels are said to be unstressed. We can see the difference in stress in pairs like billow and below, which differ mostly in which syllable is stressed: the first syllable in billow and the second syllable in below. The two central vowels of English differ in stress: the first syllable of the name Bubba is stressed, and the second is unstressed, so we might transcribe this name as [bʌbə]. Although these two vowels sound very similar for many speakers and could easily be notated with the same symbol, there is a long tradition of notating the unstressed mid central vowel of English with [ə] and the stressed mid central vowel with [ʌ], based on historical pronunciations in which the stressed vowel used to be pronounced much farther back (and still is, in some dialects).

Subsection The IPA in the real world: A warning

The IPA is a very useful notation system, not only for theoretical research, but also in many practical contexts. Most importantly, it can be used in dictionaries and other reference materials to describe the pronunciation of words in an unambiguous way.

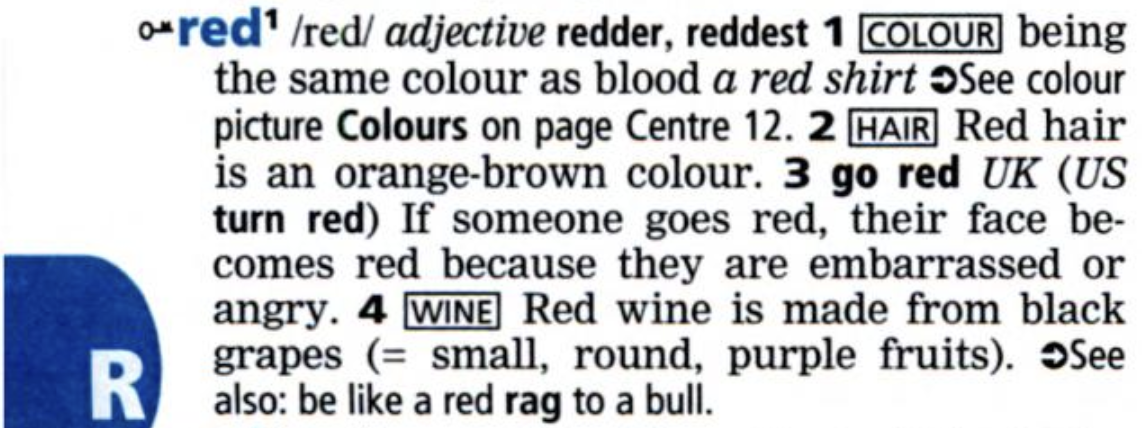

At least that is the theory. Unfortunately, you will encounter quite a bit of ambiguity in the real world, because publishers of reference materials often use the IPA in very idiosyncratic ways. In order to reduce the number of unfamiliar symbols for their readers, and perhaps also out of pure laziness, they will often use a typographically simpler character to represent a phone even if that character has the wrong value. In British and American English, for example, the phone [e] never occurs by itself. This has prompted dictionary makers to print [e] in places where the correct IPA character would be [ɛ]. Similarly, British and American English do not have the voiced alveolar trill [r], so dictionary makers us the character [r] instead of the correct [ɹ]. The excerpt from the Cambridge Learners Dictionary shown in Figure 3.6.9 illustrates both practices at once.

The entry for the word “red” in the Cambridge Learner’s Dictionary. The phonetic transcription given is “red”.

This practice means that you always have to check how a particular reference work uses the IPA — this is precisely the problem that the IPA was meant to avoid.

You will also find the IPA symbols used in an imprecise way that may seem similar at first glance but that actually has different reasons (not better, just different). We will come back to these in Chapter 4.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adapted from Catherine Anderson, Bronwyn Bjorkman, Derek Denis, Julianne Doner, Margaret Grant, Nathan Sanders, and Ai Taniguchi, Essentials of Linguistics. 2nd ed. with additions and extensions by Anatol Stefanowitsch and edits by Kirsten Middeke and Berit Johannsen.