Section 3.5 Describing vowels

Subsection Vowel quality

Vowel phones can be categorized by the configuration of the tongue and lips during their articulation, which determines the vowel’s overall quality. Vowel quality is often much more of a continuum than consonant categories like place and manner. A slight change in articulation makes little difference in what a vowel sounds like, but it can have a drastic effect on a consonant. For example, moving an active articulator away from a passive articulator by just a tiny bit, less than 1 mm, is enough to turn a stop into a fricative, but that same distance for a vowel will have no noticeable effect. However, we can still identify several broad categories of vowel qualities based on dividing up this continuum into a few major regions.

Subsection Openness

Vowels are articulated with a larger opening of the oral cavity than consonants are, requiring the tongue to move farther down than for approximants. This is typically facilitated by also moving the jaw down to allow the tongue to move even lower. The size of the resulting opening is the first dimension along which vowels are categorized. There are two competing terminologies for this dimension: some researchers describe the opening in terms of the height of the tongue and distinguish between high vowels (the tongue is high, i.e. the opening is relatively small) and low vowels (the tongue is low, i.e., the opening is relatively large). Other researchers refer to the degree of openness itself and distinguish between close vowels (the opening is small) and open vowels (the opening is large). In both terminologies, we can also distinguish various degrees between high/close and low/open. We will follow the second strategy here, as it is the one standardized by the International Phonetics Association (see further Section 3.6).

Examples of close vowels (or high vowels) are the vowels in the English words beat and boot; examples of open vowels (or low vowels) are the vowel in the English word bat and the one in the North American pronunciation of the word bot. Close vowels have an opening just slightly larger than approximants. Indeed, close vowels and approximants are often related in many languages, with one turning into the other in certain positions. Compare the different pronunciations of the phone represented by the letter i in the middle of the English words unique (with a close vowel) and union (with an approximant).

Open vowels have a much larger opening than any consonants, in fact, they have the largest opening of the oral cavity of any phones.

Vowels with an opening that is slightly smaller than that of open vowels are those in the words bet or in the British English pronunciation of the word bot. These are called open-mid vowels. There are also vowels with an opening that is slightly larger than that of close vowels, but not as large as that of open-mid vowels, for example the beginning of the vowel in bait or the vowel in the Scottish English pronunciation of the word boat (or the corresponding German word Boot). These are called close-mid vowels.

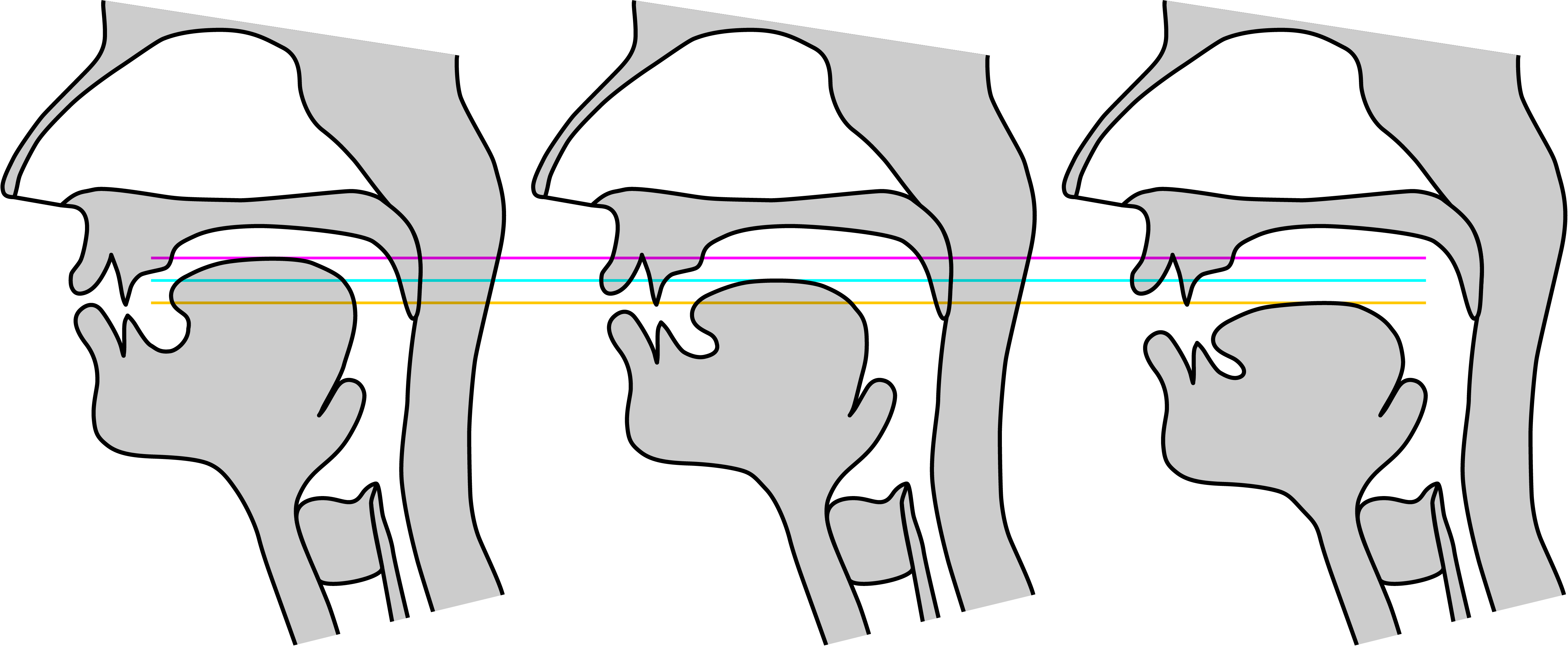

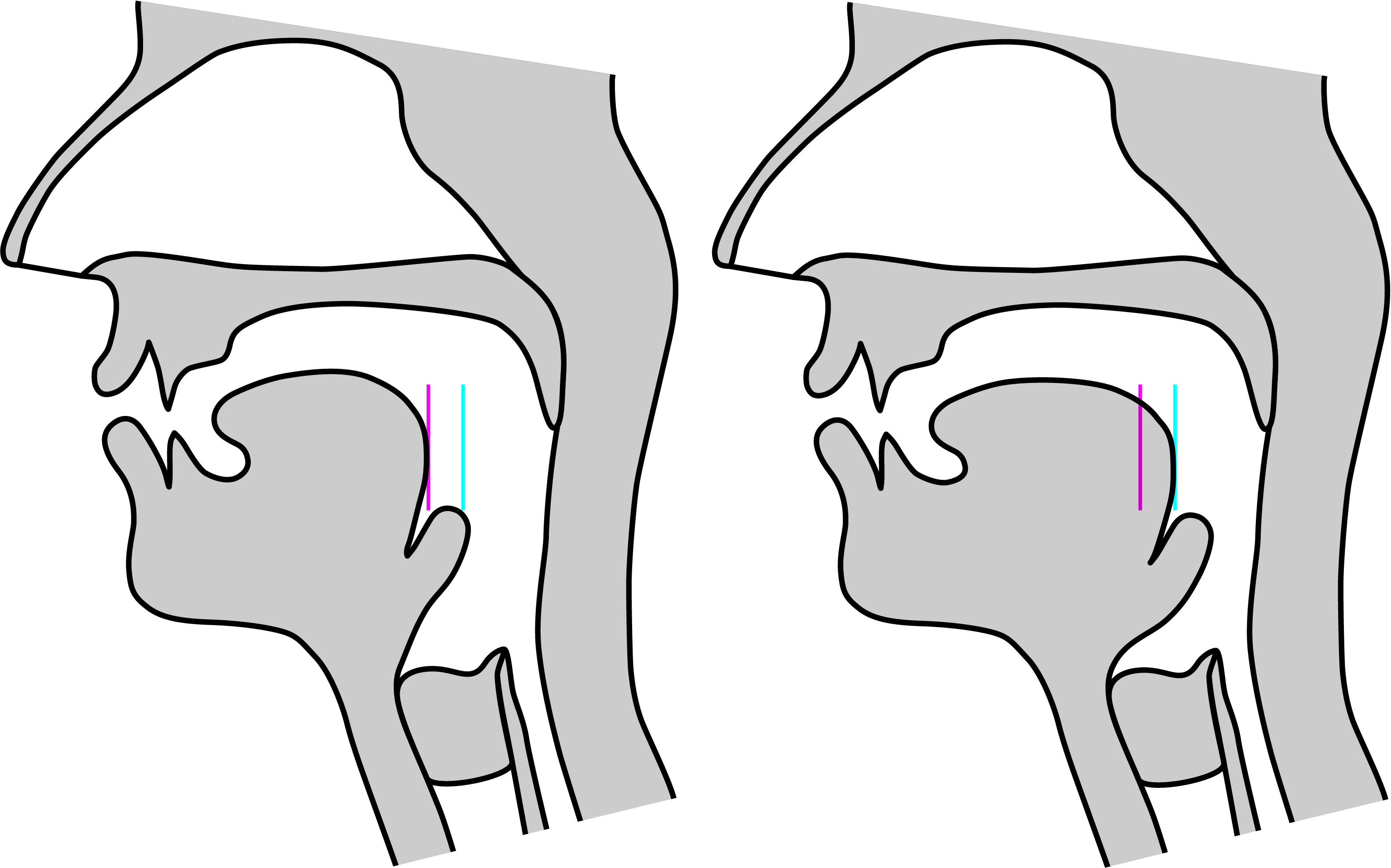

Figure 3.5.1 shows three vertical tongue positons — that for close vowels on the left, that for open vowels on the left, and an intermediate position somewhere between close-mid and open-mid vowels. Note how the jaw lowers along with the tongue in these diagrams.

Three midsagittal diagrams, showing a high tongue position, a mid tongue position, and a low tongue position. Each height is also represented with a line across all three diagrams for ease of comparison: close (magenta), mid (cyan), and open (yellow).

Subsection Backness

The horizontal position of the tongue, known as its backness, also affects vowel quality. Backness could equally be called frontness, and sometimes this term is used, but “backness” is more standard and preferred. If the tongue is positioned in the front of the oral cavity, so that the highest point of the tongue is under the front of the hard palate, as for the vowel in the English word beat or bat, the vowel is called a front vowel.

If the tongue is positioned farther back in the oral cavity, so that the highest point of the tongue is under the back part of the hard palate or under the velum, as in the English word boot or bot (in the American or British pronunciation), the vowel is called a back vowel.

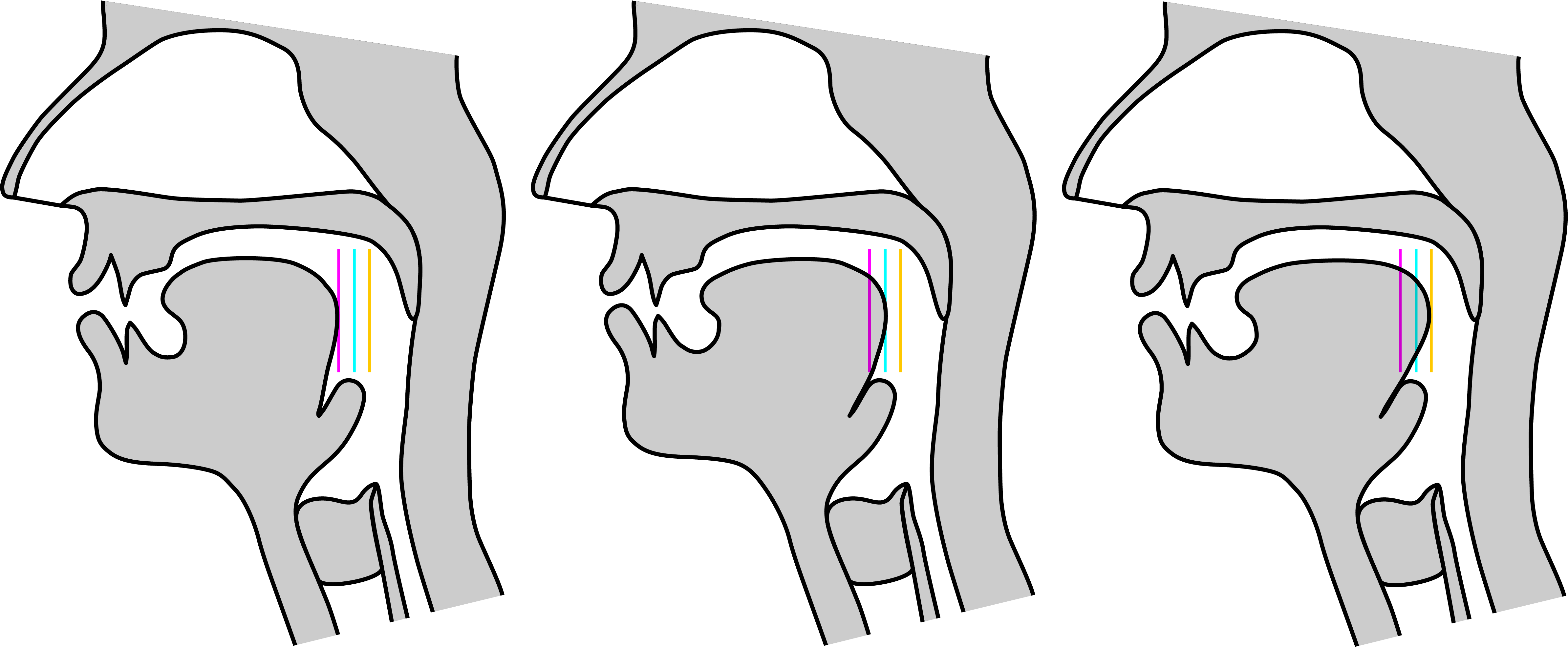

If the tongue is positioned in the centre of the oral cavity, so that the highest point of the tongue is roughly under the centre of the hard palate, in between the positions for front and back vowels, as for the English word but, the vowel is called a central vowel. Be careful not to confuse the technical terms central and mid (in open-mid and close-mid). Central refers to an intermediate position in backness, while mid refers to an intermediate position in openness (height). These two terms are not interchangeable! The differences in horizontal tongue position for these three categories of vowel backness are shown in Figure 3.5.2 from frontest on the left (as in beat) to backest on the right (as in boot).

Three midsagittal diagrams, showing a front tongue position, a central tongue position, and a back tongue position. Each backness is also represented with a line in the same position in all three diagrams for ease of comparison: front (magenta), central (cyan), and back (orange).

Note that what counts as front for a vowel depends on its openness, because of how the jaw moves. Humans have a hinged jaw, which means that as the jaw moves down to create a larger opening, it also swings backward, carrying the tongue along with it. As the tongue moves backward due to this hinged movement, its centre position also moves backward, and it becomes more difficult for this lowered tongue to move as far forward as for a more close vowel.

In fact, the most front (phoneticians sometimes say frontest) position for am open vowel (as in the English word bat) typically has an actual overall backness a bit farther back than for a front close vowel (as in the English word beat). Thus, backness must be defined relative to the possible range of horizontal positions at a given degree of openness, rather than being defined in absolute terms with respect to the roof of the mouth, which results in a skewed shape of the possible combinations of vowel height and backness, with more distance between front and back positions for close vowels than for open vowels.

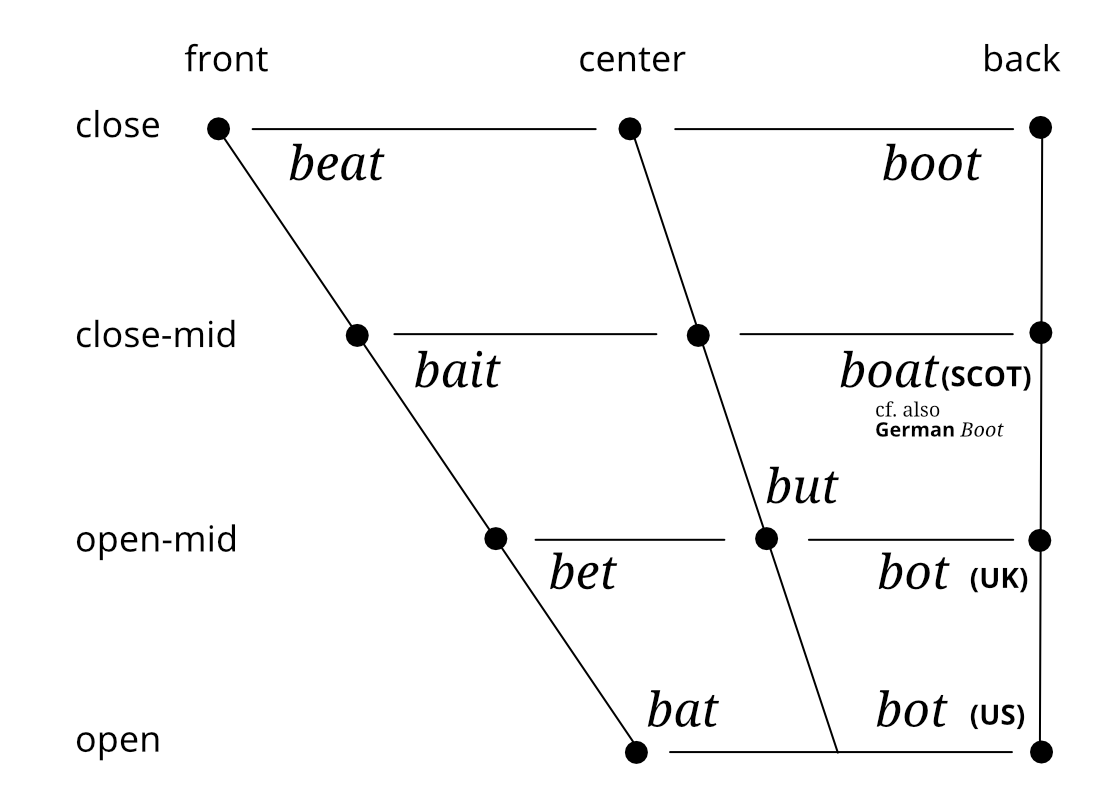

This is often graphically represented as in Figure 3.5.3, with the total vowel space drawn as an asymmetric quadrangle, like a rectangle with the bottom left corner cut off. This missing corner represents the space where humans cannot produce a vowel because of the how the tongue moves backward as the jaw lowers. A few example words of English are listed in as a rough indications for what tongue position many speakers use for the vowels in these words.

Quadrangle with lower left corner cut off, divided into nine cells, labelled front, center, and back across the top, and close, close-mid, open-mid and open down the right side. Inside the cells are the English words: beat in the front close cell, bait in the front close-mid cell, bet in the front open-mid cell, bat in the front open cell, but in the center open-mid cell, boot in the back close cell, boat (Scot. Eng.) and Boot (German) in the back close-mid cell, boat in the back close-mid cell, bot (UK) in the back open-mid cell and bot (US) in the back open cell.

The cells in this quadrangle represent possible positions of the tongue within the oral cavity. For example, beat is shown in the close front cell, which indicates that it is pronounced with a close front tongue position. Note that there is much variation in English vowels across speakers, so the positions in Figure 3.5.3 are only meant to be suggestive of broad patterns across a range of dialects. The positions of the tongue for the vowels in these words may be somewhat different for you or for other speakers. For example, some speakers may have an open or back vowel for but, and some may have a more central vowel for bot or boat.

Subsection Rounding

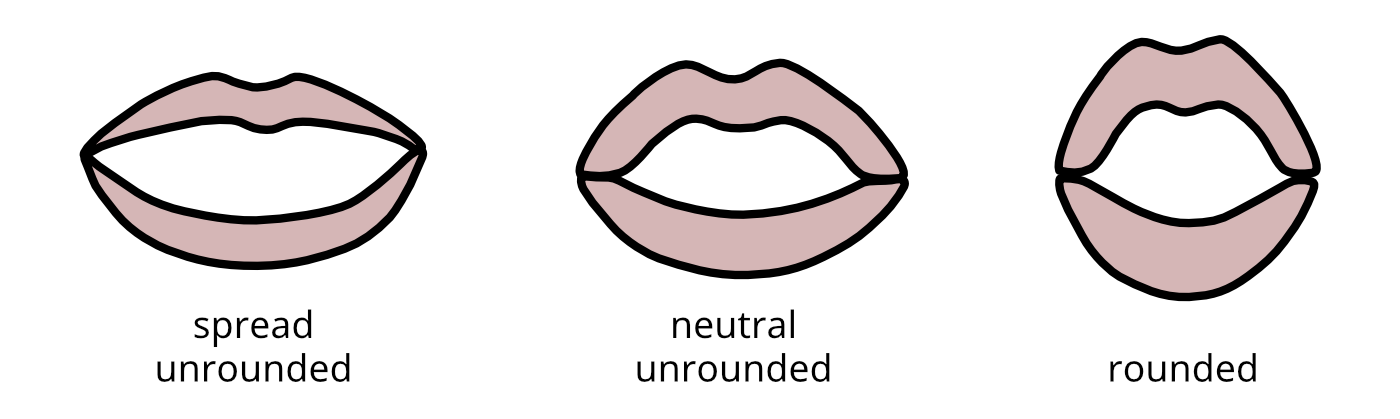

Vowel quality also depends on the shape of the lips, generally referred to as the vowel’s rounding. If the corners of the mouth are pulled together so that the lips are compressed and protruded to form a circular shape, as for the vowel in the English word boot in many dialects, the lips are said to be rounded and the corresponding vowel is called a round or rounded vowel.

If the corners of the mouth are pulled apart and upward so that the lips are thinly stretched into a shape like a smile, as for the vowel in the English word beat, the lips are said to be spread.

The lips may also be in an intermediate configuration, neither rounded nor spread, as for the vowel in the English word but, in which case, the lips are said to be neutral. Spread and neutral vowels are collectively referred to as unrounded or non-rounded vowels, because the distinction between spread and neutral lips seems almost never to be needed in any spoken language, whereas the distinction between rounded and unrounded frequently is needed. The differences in lip shape for these three categories of vowel rounding are shown in Figure 3.5.4

Three sets of lips in different configurations: spread unrounded, neutral unrounded and rounded.

Subsection Tenseness

The position of the tongue root may also play a role in vowel quality. If the tongue root is advanced forward away from the pharyngeal wall, as for the vowel in the English word beat, the tongue root pushes into the rest of the tongue. This causes the tongue to be somewhat denser and firmer overall, so a vowel with an advanced tongue root is sometimes called a tense vowel. If the tongue root is instead in a more retracted position closer to the pharyngeal wall, as for the vowel in the English word bit, it keeps the tongue somewhat more relaxed, so a vowel with a retracted tongue root is sometimes called a lax vowel. The property of whether a vowel is tense or lax is called tenseness. The different positions of the tongue root for tense and lax vowels are shown in Figure 3.5.5

Two midsagittal diagrams, the left with an advanced tongue root and the right with a retracted tongue root. Each tenseness is also represented with a line in the same position in both diagrams for ease of comparison: tense (magenta) and lax (cyan).

Languages differ in how tense or lax their vowels are, but for many languages, the distinction between the two is not a relevant property. However, there are spoken languages that have more complex vowel systems, with vowel pairs articulated in roughly the same way, except for tenseness. For example, most dialects of English have multiple pairs of vowels that are distinguished primarily by tenseness, such as the vowels in beat and bit. Both of them have a high front tongue position and are unrounded, but the beat vowel is tense, while the bit vowel is lax. Thus, for languages like English, the terms tense and lax are useful in describing the vowel system.

Note that there are linguists who doubt the relevance of this distinction. They argue that lax vowels are more centralized than tense vowels and that the front-central-back dimension is sufficient to describe the difference between them. This is certainly true for English, where the lax vowels in bit or full are more central than their tense counterparts in beat and fool. In many languages, there is also a correlation between tenseness and length: tense vowels are often longer in duration than lax vowels. This is true of some varieties of English (e.g. British English) but not others (e.g. General American English), so length would not be sufficient to capture the distinction across languages.

Subsection Length

While it is no alternative for the tense-lax distinction, length (duration) can be a relevant distinction for vowel phones in spoken languages. In most spoken languages where vowel length matters, there is just a two-way distinction between long vowels and short vowels. For example, in Japanese (a Japonic language spoken in Japan), the word いい ‘good’ and the word 胃 ‘stomach’ have the same vowel quality in terms of openness, backness and roundness: they are both close front unrounded vowels. However, いい has a long vowel and 胃 has a short vowel.

Vowels with the same quality may differ in length even in languages where this distinction does not matter. For example, English vowels are often pronounced a bit longer before voiced consonants than before voiceless consonants. Thus, the vowel in the English word bead is usually pronounced longer than the vowel in the word beat, even they both have the same vowel quality: close front unrounded.

By the way, consonants may also differ from each other in length in some languages. Long consonants are often called geminates, while short consonants are called singletons. English does not really make regular use of consonant length, though there are some marginal examples for some speakers, such as unnamed (with a geminate alveolar nasal) versus unaimed (with a singleton alveolar nasal). However, many other languages have widespread distinctions based on consonant length.

For example, geminates and singletons are contrasted in Hindi (a Central Indo-Aryan language of the Indo-European family, spoken in India). Hindi has word pairs like सम्मान (sammān) ‘honour’ (with a geminate bilabial nasal in the middle of the word) versus समान (samān) ‘equal’ (with a singleton bilabial nasal in the middle of the word).

Subsection Nasality

In Section 3.4, we talked about how the velum can move to make a distinction between oral and nasal stops based on whether or not air can flow into the nasal cavity. The same distinction can be found for vowels. If a vowel is articulated with a raised velum to block airflow into the nasal cavity, the vowel is called oral. If instead the velum is lowered, allowing airflow into the nasal cavity, the vowel is called nasal or nasalized. The property of whether a vowel is oral or nasal is called its nasality. Vowels in most dialects of English are often nasal when they are immediately before a nasal consonant, as in the English word bent. In other languages, nasality does not depend on the presence of nasal consonants. For example, in French, the words gras (‘fat’) and grand (‘great’) end in a vowel with the same openness, backness and roundedness: an open, back, unrounded vowel. However, that vowel is oral in gras and nasal in grand.

Subsection Multiple vowel qualities in sequence

The vowel phones we have discussed so far all have a relatively stable pronunciation from beginning to end: their openness, backness and roundedness do not change perceptibly. These kinds of vowel phones are called monophthongs. However, just as there are consonant phones that change their articulation from beginning to end — affricates like the sound at the beginning of chin or gin —, vowel phones may also change their articulation from beginning to end.

The most typical case of such vowels are diphthongs, which begin with one specific articulation and shift quickly into another, as with the vowel in the English word toy, which begins with an open-mid back round quality but ends close, front, and unrounded. As with affricates, it can be difficult to determine whether a given change in vowel quality is best treated as a true diphthong or instead as a sequence of two separate monophthongs.

Some languages can even have triphthongs, which are vowel phones that change from one vowel quality to another and then to a third, as in rượu ‘alcohol’ in Vietnamese (a Viet-Muong language of the Austronesian family, spoken in Vietnam and China). The word rượu has a vowel phone that begins with a close central unrounded quality, then lowers to a mid position, and then finally ends in a close back position with rounding.

Subsection Putting it all together!

There is not as much consistency in the order of descriptions for vowels as for consonants. Perhaps the most common order is openness – backness – rounding, but rounding is sometimes given first instead, and though openness is usually given immediately before backness, these can also be switched. Thus, the vowel in the English word bet might be described as an open-mid front unrounded vowel, or as an unrounded open-mid front vowel, or as a front open-mid unrounded vowel, or as an unrounded front open-mid vowel. All of these would be considered correct.

When descriptions of nasality are needed, they are almost always placed after the description of vowel quality. Thus, the vowel in the English word bent might be described as an open-mid front unrounded nasal vowel, or as an unrounded open-mid front nasal vowel, but rarely as a nasal open-mid front unrounded vowel.

If descriptions of tenseness or length are also needed, these are often placed before the other descriptions, but sometimes either or both may be placed after vowel quality, but usually still before the position for the description for nasality. Thus, the vowel in the English word bend could be described as a long lax open-mid front unrounded nasal vowel, or as a lax open-mid front unrounded long nasal vowel, or as an unrounded open-mid front long lax nasal vowel, or many other combinations!

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adapted from Catherine Anderson, Bronwyn Bjorkman, Derek Denis, Julianne Doner, Margaret Grant, Nathan Sanders, and Ai Taniguchi, Essentials of Linguistics. 2nd ed.; terminology updated to IPA, figures redrawn; restructured and extended by Anatol Stefanowitsch.