Section 3.4 Describing consonants: Manner

Consonant phones can also be categorized by their manner of articulation (or manner for short), which is how air flows through the vocal tract, based on the size and shape of the constriction between the articulators.

Subsection Plosives

The most basic manner of articulation is the stop, in which the active articulator presses firmly against the passive articulator to make a complete closure, blocking all airflow at that point. In the context of the type of phonation we are concerned with here — one based on airflow from the lungs —, there are two major types of stops: plosives, where the airflow is stopped completely and then released in an explosive burst, and nasals, where there is a complete closure in the oral cavity, but where velum is lowered to allow airflow through the nasal cavity. Plosives are the most common type of stop, so let us look at them first before we come back to nasals.

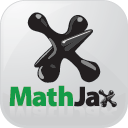

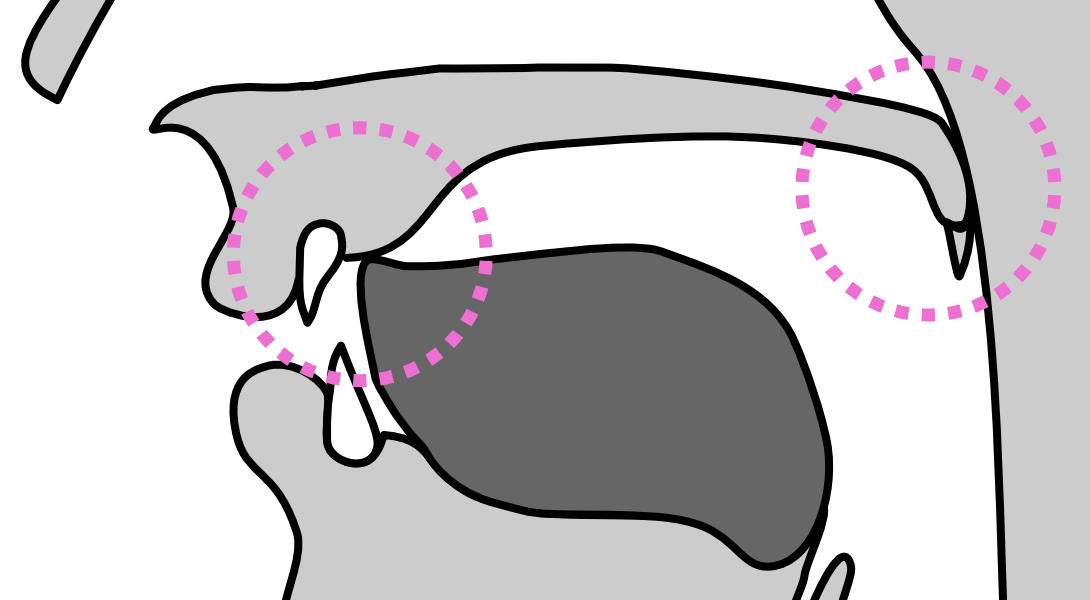

Figure 3.4.1 shows the tongue position for an alveolar plosive (the sound at the beginning of the word dog if it is voiced, i.e., if the vocal folds are closed and vibrating, or tail if it is is unvoiced, i.e., if the vocal folds are not vibrating). Figure 3.4.2 shows the tongue position for a dorsovelar plosive (velar for short); the sound at the beginning of the word goat if it is voiced, and at the beginning of the word coat if it is unvoiced). In both cases, the velum is raised and the nasal cavity is closed off, so the closure is complete and there is no airflow at all until the tongue moves away from the respective passive articulator.

Midsagittal diagram of the front of the tongue making contact with the alveolar ridge and the velum raised against the paryngeal wall, closing off the nasal cavity from the oral cavity.

Midsagittal diagram of the back of the tongue making contact with the velum, which is raised against the paryngeal wall, closing off the nasal cavity from the oral cavity.

Subsection Nasals

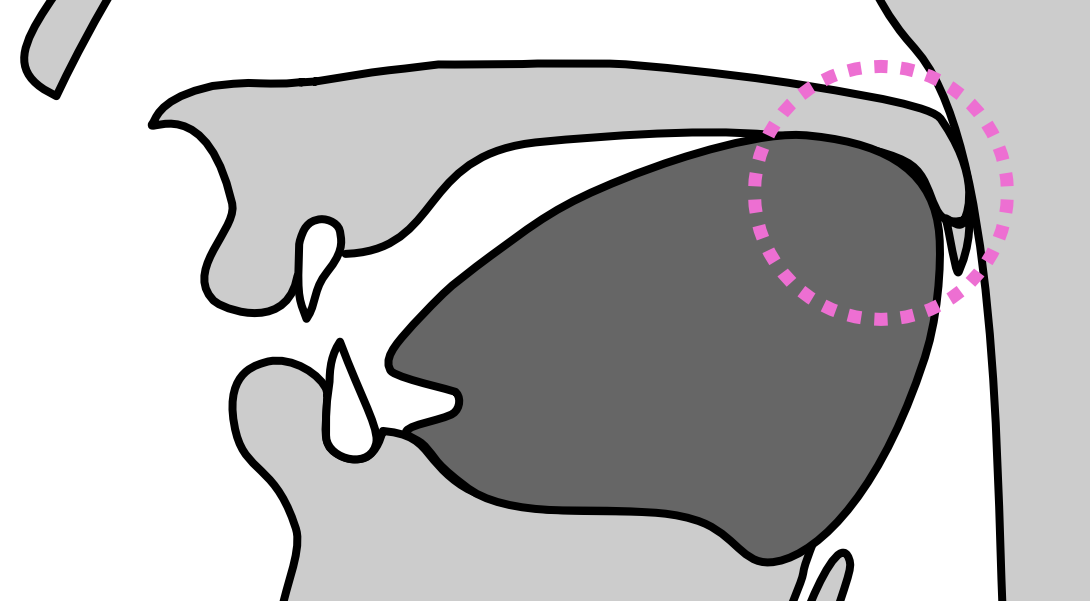

Figure 3.4.3 shows the position of tongue and velum in the articulation of an alveolar nasal (the sound at the beginning of the word nail). As you can see, the tongue position is identical to that of the alveolar plosive at the beginning of the word tail, but the velum is lowered so that the air from the lungs can flow through the nasal cavity. Phones with a total closure in the oral cavity and airflow through the nasal cavity are sometimes called nasal stops, but this terminology is confusing because the airflow is not stopped in the nasal cavity. We will therefore follow more modern terminology and simply call these sounds nasals.

Midsagittal diagram of the front of the tongue making contact with the alveolar ridge and the velum lowered, so that there is no closure between the oral and the nasal cavity.

Subsection Other types of stops

Most languages have plosives as their only oral stops, and since nasal stops are normally referred to simply as nasals, the terms plosive and (oral) stop are often used interchangeably in the linguistic literature on these languages. However, in more careful work, they must be distinguished, because plosives are only one kind of oral stop. Other kinds of oral stops include: ejectives, in which air is pushed up by raising the vocal folds rather than exhaling from the lungs (found, for example, in Hausa and Georgian); implosives, in which air is sucked in by lowering the vocal folds (found, for example, in Igbo and Sindhi); and clicks, in which air is sucked in by quickly lowering the tongue (found, as mentioned in Section 3.2, in the Khoisan languages and in some Bantu languages).

Subsection Fricatives

If the active and passive articulators are very close but not touching, creating a narrow constriction, airflow through this constriction becomes very turbulent, resulting in highly random noisy airflow called frication, which sounds like hissing or buzzing. A phone articulated this way is called a fricative. The English words set and vet begin with fricatives.

Subsection Approximants

If the active and passive articulators are not touching and are spaced far enough apart to create little or no frication in the airflow, then the resulting phone is called an approximant. Most approximants have relatively unrestricted airflow through the middle of the oral cavity and are called central approximants. However, during the articulation of an approximant, part of the tongue may instead make full contact with an upper articulator, causing the airflow to be diverted along one or both sides of the tongue, but still without frication. Such an approximant is called a lateral approximant. The English words yet and wet begin with central approximants, while the English word let begins with a lateral approximant.

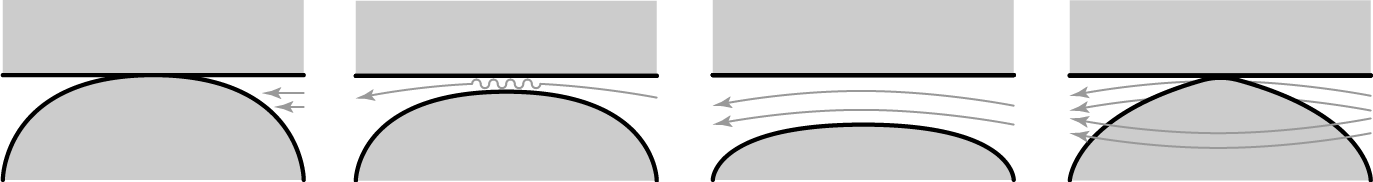

These four manners of articulation are schematized in the diagrams in Figure 3.4.4, in which the flat bars across the top of each diagram represent the midsagittal view of some arbitrary passive articulator, such as the alveolar ridge or hard palate, while the rounded shapes represent some active articulator, such as the tongue tip or tongue back, and arrows represent the nature of the airflow during the consonant.

Four diagrams showing two stylized articulators and their relation: Full closure, near closure (causing vibration as the air passes through), proximity without closure, allowing air to pass without causing vibration, and central closure with air being able to pass around the sides.

The stop (far left in Figure 3.4.4) has a complete closure between the two articulators, preventing airflow from getting past, indicated by the short airflow arrows that do not continue past the closure. The fricative (second from the left) has a narrow opening with tightly constrained, fricated airflow, indicated with a wavy line in the middle of the airflow arrow. The central approximant (third from the left) has a wider opening with relatively unobstructed airflow, indicated by the gently curved arrows. Finally, the lateral approximant (far right) also has a wide aperture, but with a small central obstruction that forces airflow to be diverted around the sides of the obstruction.

Subsection Affricates

Normally, the stop closure for a plosive is released relatively quickly, allowing the air to begin flowing almost immediately. However, it is also possible to release the closure slowly, so that a very brief fricative-like sound is created, causing the release of the plosive to have some frication, in which case, we say that it has a fricated release. A plosive with such a fricated release is often referred to as an affricate, which is a fifth kind of manner of articulation. The English words jet and chat begin with an affricate.

Careful study of the language is usually required to determine what is really going on when you encounter some sort of plosive followed by some frication. In this textbook, you will be told whether you are dealing with an affricate or not. It can be difficult to determine the difference between a true affricate versus a sequence of a true plosive followed by a true fricative, because they are both very similar. In some languages, the difference between an affricate and plosive-fricative sequence can change the meaning, as in English with ratchet (with an affricate) versus rat shit (with a plosive followed by a fricative). The distinction is marginal in English, occurring only at syllable boundaries (syllables will be discussed in more detail in Section 3.7), but it is more central in other languages, such as Polish. The Polish word czy ‘if, whether’ begins with an alveolar affricate, while trzy ‘three’ begins with an alveolar plosive followed by a postalveolar fricative.

Although most affricates are articulated as plosives with a fricated release, it is possible for other kinds of oral stops to have fricated releases, so ejective affricates, implosive affricates, and click affricates also exist in some of the world’s spoken languages.

Subsection Other manners of articulation

There are many other manners of articulation that are beyond the scope of this textbook. Two notable ones that do need to be mentioned here are taps (also called flaps) and trills. Taps are like stops, except that the closure is so short that airflow is barely interrupted. The consonant in the middle of the English word atom is articulated as a tap for most North American speakers.

Trills are like repeated taps, in which one articulator vibrates quickly against the other, usually 2–3 times. Most dialects of English do not have trills, though some speakers of Scottish English may have a trill for the first consonant of run. Some languages have both a tap and a trill, such as Spanish, which has a tap in the middle of the word pero ‘but’ and a trill in the middle of the word perro ‘dog’.

Subsection Other classes of consonants

Sometimes it is useful to group manners of articulation into larger categories when describing the sound systems of individual languages or comparing sound systems of different languages (see Chapter 4 for more information). Oral stops, fricatives, and affricates together form the class of obstruents, which are defined by having an overall significant obstruction to free airflow in the vocal tract. Consonants with the remaining manners of articulation (nasals, approximants, taps, and trills) form the class of sonorants, which have fairly unrestricted airflow, either through the nasal cavity (for nasals) or through the oral cavity (for approximants, taps, and trills).

Fricatives and approximants, because of their continuous airflow through the oral cavity, can be referred to collectively as the class of continuants (sometimes trills are grouped with the continuants as well).

Note that the terms sonorant and continuant are typically used to refer only to consonants, but it is sometimes useful to define these classes to include vowels as well (we will look at vowels in Section 3.5).

Subsection Putting it all together!

We now have three different ways to talk about how a consonant phone is articulated: its place of articulation, its phonation (in the case of English, voicing), and its manner of articulation. We can put these three together to give a complete description of the most common consonant phones. There are many consonants that go beyond this three-part description and require a bit more information to be fully specified, but for the purposes of this textbook, these three categories will be sufficient.

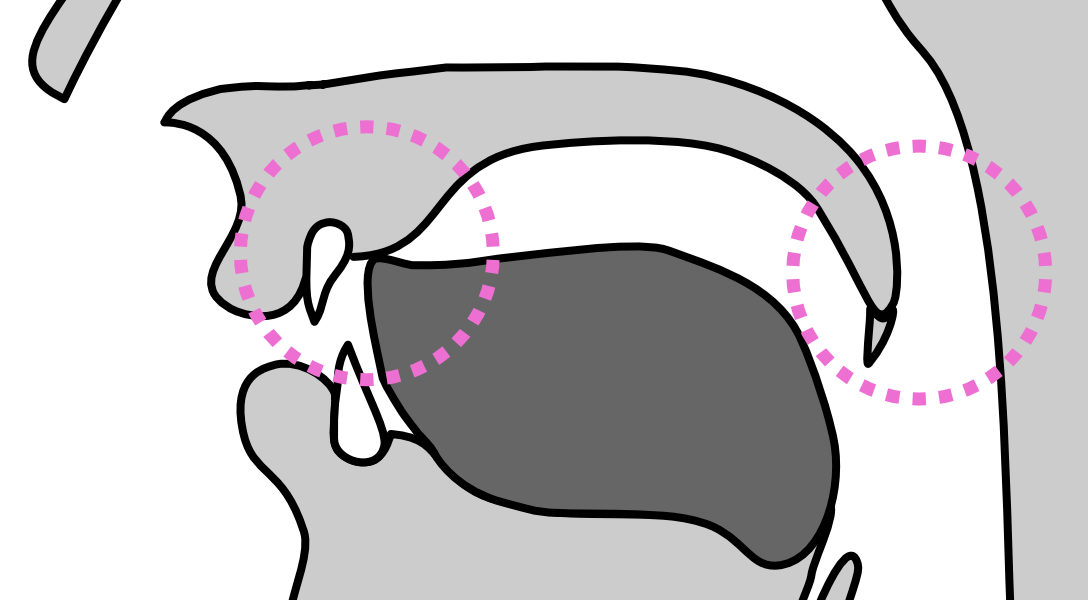

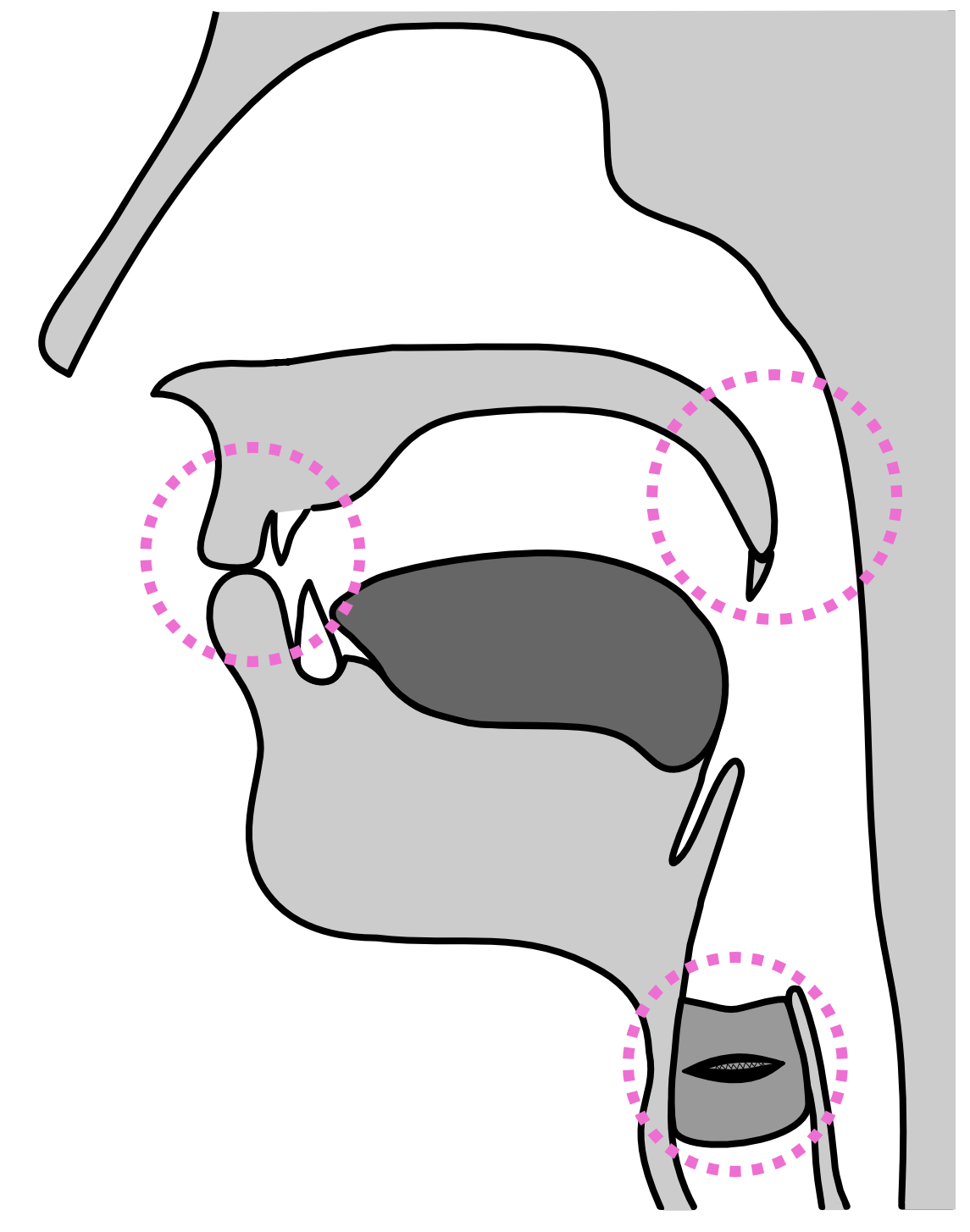

Consider the consonant phone at the beginning of the English word mail, which has the articulation shown in the midsagittal diagram in Figure 3.4.5, with the three crucial aspects of the articulation circled.

Midsagittal diagram showing the upper and lower lips touch, the velum lowered, and the vocal folds vibrating.

This consonant involves articulation of both lips, so it has a bilabial place of articulation. While saying this consonant, our vocal folds vibrate, so it is voiced. Finally, the two articulators are pressed firmly together, allowing no airflow through the oral cavity, but the velum is lowered to allow airflow through the nasal cavity, so this consonant has a nasal manner of articulation.

Conventionally, these three components in the description of a consonant phone are put in the order voicing - place - manner, so the consonant at the beginning of the English word mail would be fully described as a voiced bilabial nasal. Because it is a nasal, we can also further classify this consonant as a sonorant, if necessary.

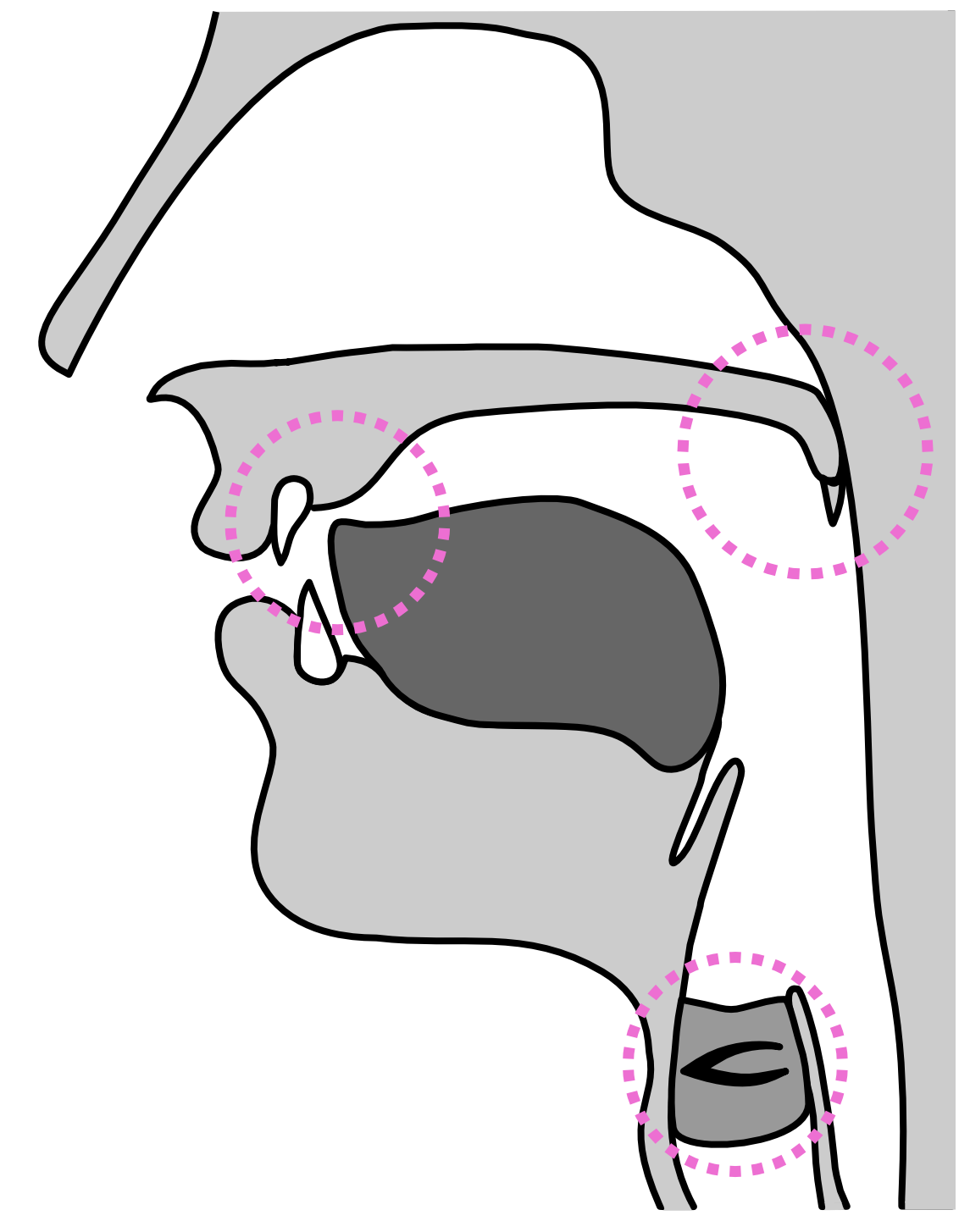

For another example, consider the consonant phone at the beginning of the English word sail, which has the articulation shown in the midsagittal diagram in Figure 3.4.6, with the three crucial aspects of the articulation circled.

Midsagittal diagram showing the tongue front near the the alveolar ridge, the velum raised, and the vocal folds not vibrating.

This consonant involves active articulation of the front of the tongue; most speakers use the tongue tip, but some may use the tongue blade, either instead of the tip or in addition to it. The passive articulator of this phone can be hard to determine, since the front of the tongue is not touching it, but rather, is separated slightly from it. However, you can sometimes feel what the passive articulator is by breathing in instead of blowing out, because this can cause the passive articulator to become slightly cooler. If you do that with this consonant, you should feel the alveolar ridge getting cooler. Thus, this consonant has an alveolar place of articulation, and whether that place is apical (the default) or laminal depends on the individual speaker.

For this consonant, the vocal folds do not vibrate, so it is voiceless. Finally, the two articulators are separated very slightly, creating loud, very turbulent airflow, so this consonant has a fricative manner of articulation. Putting it all together, this consonant phone is a voiceless alveolar fricative, or voiceless apicoalveolar fricative, or for some speakers, a voiceless laminoalveolar fricative, if we want to be precise about which active articulator is used. Because it is a fricative, we can also further classify this phone as both an obstruent and a continuant.

Also note that for this consonant, the velum is raised and backed to block airflow from entering the nasal cavity. Fricatives are nearly always oral consonants, because having any airflow leak into the nasal cavity makes it difficult to produce high enough air pressure to force airflow through the narrow fricative opening.

We will look more closely at how to describe some more consonants at the end of this chapter, but for now, focus on understanding the definitions of the various terms that are used to fully describe a consonant’s voicing (phonation), place, and manner.

Subsection

CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adapted from Catherine Anderson, Bronwyn Bjorkman, Derek Denis, Julianne Doner, Margaret Grant, Nathan Sanders, and Ai Taniguchi, Essentials of Linguistics. 2nd ed.; with additions and redrawn figures by Anatol Stefanowitsch and minor edits by Kirsten Middeke and Berit Johannsen.